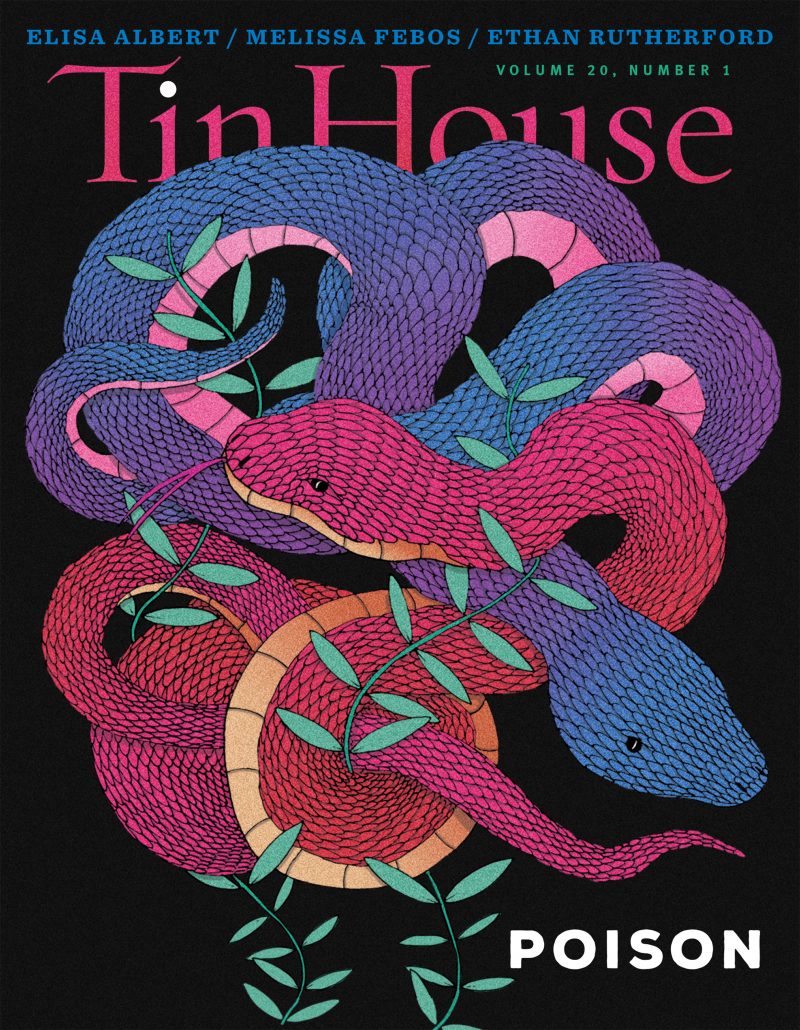

In the midst of the #MeToo movement, Tin House’s poison-themed issue addresses the uncomfortable and toxic times we live in. In this collection, many of the stories, essays, and poems show the struggles women face and the ways they take back agency of their own bodies, making Tin House‘s Fall 2018 issue more important than ever in America’s current political climate.

In her essay “Intrusions,” Melissa Febos recounts a terrifying stalking she endured while living in New York and working as a dominatrix. She recalls how a strange man used to stand outside her window at night, grunting and groaning inappropriate things as she felt more and more unsafe in her own home. Febos encountered voyeurs and exhibitionists while working as a dominatrix, but this stalking and “peeping” was crossing new boundaries, the fetishes transformed into something harmful when she was off the clock. “Intrusions” is an exploration of consent and privacy, as well as an interrogation of the unchecked male gaze, as the violation that Febos encounters is all but ignored by the police and minimized by the law itself. From Rear Window to Revenge of the Nerds, Febos analyzes how stalking has been romanticized or portrayed as a viable way for the man to “get the girl.” She also addresses the prevalence of violence toward women in popular television, how even the incredibly well-known NCIS: Special Victims Unit may not promote the sexual and violent abuse of women, yet still the show spotlights these crimes. This desensitization in our culture that is now being exposed through the #MeToo movement is laid bare in “Intrusions.”

Lory Bedikian’s poem “Partial Tubectomy Revisted” also examines female agency and autonomy, though in terms of reproduction. Written in three-line stanzas, Bedikian describes a miscarriage using visceral imagery—old furniture slipping and crashing, a nail driven into a tire, “uncontrollable writhing”—to elicit an intense emotional response. As the reader witnesses the events unfold, the rights of the speaker’s body are transferred to medical professionals who claim to have saved her life, and through the loss the speaker remembers women of the past, others who were not so lucky. In the midst of political debates concerning reproductive rights, Bedikian’s description of one woman’s experience could not be more timely.

Along a similar theme, Katie Coyle’s “The Little Guy” focuses on sexual agency in the tumultuous relationship between Dodie and Harris. Their relationship begins with the question, “I have to ask – are you a virgin?” Dodie doesn’t feel her answer to this question is really of any consequence. She sleeps with Harris, though she doesn’t sleep with him that night, but the next time they meet, asserting her authority over her own sexuality. However, Dodie is only in control for so long before mice begin to infest her home. Her slow psychological deterioration manifests during the infestation, paralleling the recent intrusion on her body. She distances herself from those who care about her and becomes obsessed with the creatures no one else can see. She hears their scurrying at night and sees the evidence that they leave behind. Finally, Dodie realizes she must come face-to-face with what is haunting her. Coyle’s surreal short story explores the mental, physical, and social strain that is put on women when they cease to have control of their bodies, as well as the toll it takes as they fight to regain power.”The Little Guy,” like many of the pieces in Tin House‘s Poison issue, platforms the resilience and expressive creativity of women in our modern day.

—

Trison Foster is an undergraduate reader for Portland Review.