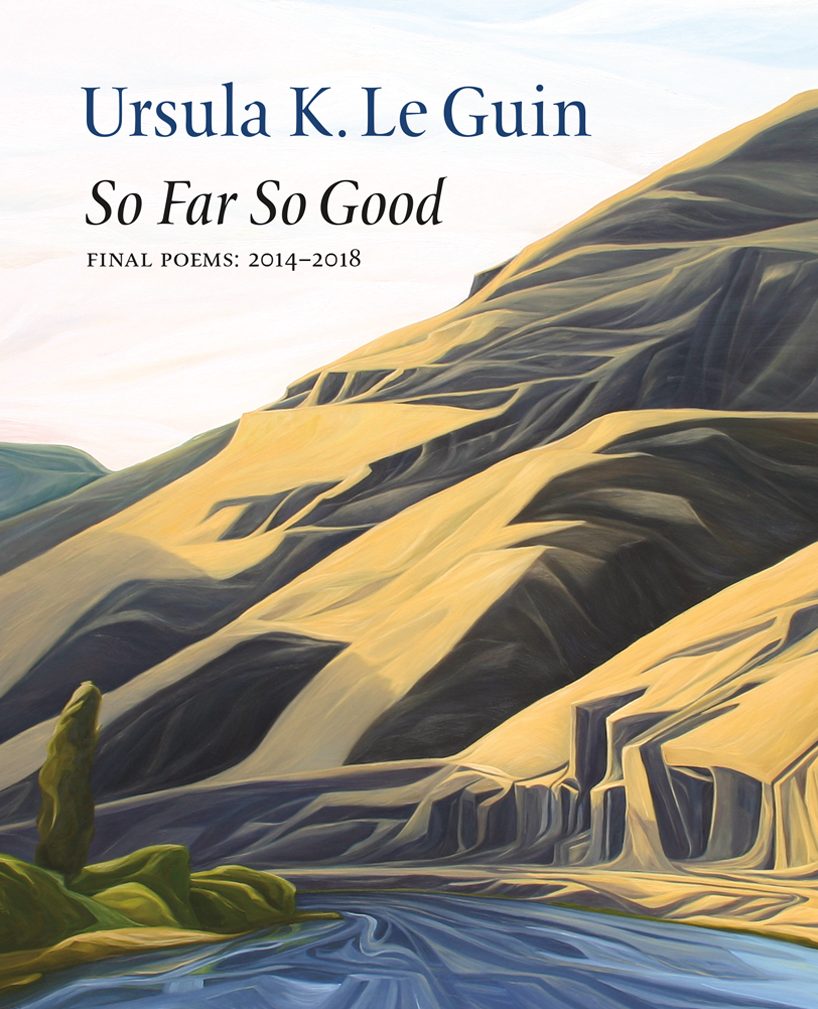

After her death at the age of 88 earlier this year, Ursula K. Le Guin unleashed a wake of spirituality, meditation, reflection, and journey upon her readers with the release of her posthumous collection of poems So Far So Good (Copper Canyon Press, 2018). The poems lead the reader on a solitary journey by way of boat, through sunrises, sunsets, and vast hills. Though the collection is divided into several sections, subsections, and subsections upon those subsections, the divided construction of this book does not detract from a continuous understanding of the poems; the collection remains a singular and cohesive experience that travels deeper into the mindset of the speaker, evoking realizations of life, human instinct, and the ongoing process of uncertainty. While So Far So Good represents Le Guin’s meditations on her life, these poems also serve as an important evocation, a posing of the questions Where am I going? and What am I leaving behind? To take the journey with Le Guin as a reader and to be objective, reflective, thankful, and understanding is to be immersed in this body of work.

In the poem “Ancestry,” Le Guin writes “I am such a long way from my ancestors now / in my extreme old age that I feel more one of them / than their descendant. Time comes round / in a bodily way I do not understand.” Throughout the course of her poems, the reader must come to terms with where they are in the world, to face their own personal odyssey and arc. Le Guin partitions So Far So Good into seven sections organized around observations, meditations, and incantations, divisions that do not cut the reader off from Le Guin’s thought processes and personal journey. Instead, the sections represent individual stops in a single exploration, each delving deeper into the dark, fluid ocean of Le Guin’s self reflection.

In general, poems in So Far So Good are extremely minimalistic, many times using only one stanza, leaving large amounts of white space on the page. The effect is a resounding echo that bounds along all edges of the page, a lasting sound reinforced by rhyme at the end of her poems. In the collection’s first poem “Little Grandmother,” Le Guin ends with “at autumn’s entropy / and quietly says this: / I am Chickadee / and things have gone amiss.” The rhyme overpowers the visible stop at the end and carries the poem into the ether of the page. While Le Guin does not always use rhyme to end her poems, her lasting images combine with the blank page to create a world of thought and peace. Even the briefest of her poems assert themselves in the space they are evoking, a space inhabited by water and the mercurial manipulation of light.

In the seventh and final section of the book entitled “The Ninth Decade,” Le Guin reflects on her age, her life in its entirety, and the nature of memory. In the ending of the last poem “On the Western Shore,” the reader senses the border, leaping into the vast space and power of the white page. Momentum and routine drop into the void, all interrupted for the first time. In one lasting breath, Le Guin gives her thoughts on reconciling one’s finality and ultimate internal legacy, presenting a landscape for her readers to travel through and past.

—

Samuel Willhalm is an MFA student at Portland State University. His poetry has been published in the Redlands Review.