Her first harmonica was a cheap Toysmith—plastic under silver paint—that ’er daddy picked up on ’is way home from work without thinkin’ the littlest bit about it. It was a toy, was all. So was ’er first guitar: an ugly purple thing with a princess on it that hadn’t been the full-size, beat-to-hell beauty she’d dreamed of after seein’ an old Willie Nelson concert on TV.

Second to music, worryin’ ’er mama was what came easiest to the little girl who scrawled this masheen kills fashists along the edge of ’er toy guitar, doodled a mustache over the princess’s smile, and got in trouble at school not jus’ for playin’ harmonica at lunchtime, but for wearin’ real flowers in ’er hair on picture day, roots rainin’ dirt down the shoulders of the shirt her mama thought might make ’er look nice.

Her mama jus’ didn’t understand how one little girl could dream different than all the others. She spent the fourteen years between ’er daughter’s first harmonica an’ ’er daughter’s last day o’ high school tryin’ so subtly to steer her toward somethin’ a little less worrisome. Easy as turnin’ plants on ’er windowsill to face the way she wanted—that’s what she thought.

But while a person can turn a plant in its pot, they never can change the way the sun moves in the sky, nor stop the plant from leanin’ after it again. In those same fourteen years, her daughter learned that music was ’er sunlight, and she’d always turn back toward it, no matter how of’en anyone tried to face ’er away.

She stopped tryin’ to be like other people an’ started strivin’ for the one her mama worried about the most: herself. An’ when she discovered how right an’ true it felt, she knew her callin’, an’ she knew she’d answer.

So she went to ’er parents and announced that she was goin’ to be a folk singer.

“Sounds hungry,” was all ’er daddy had to say about it.

First her mama laughed that she had such a strong-headed daughter. Then she asked what exactly she meant about doin’ it “for a livin’,” warned ’er she shouldn’t put all ’er eggs into a basket with the bottom cut out, begged ’er to consider somethin’ a little more reasonable, yelled at ’er to get ’er head outta the clouds, an’, finally, despaired that her daughter would be dead in a gutter by the end of the year.

“I have a few songs written already,” the folk singer told ’er mama. “Maybe if I play one, you’ll feel better about it.”

The folk singer slung ’er wood-burned-roses guitar over her head an’ strummed out a song about a girl who wouldn’t put ’er phone down for nothin’, lost in a world’f circuit daydreams blinkin’ an’ flashin’, blindin’ her eyes full till she one day stepped out in front of a train she never did see comin’ an’ BLAM! So long. Her phone alone flew free, landin’ unbroken in the yellowin’ grass along the grindin’ railroad, its search engines all blocked up with questions about the future.

The folk singer’s mama fainted backwards into the arms of the folk singer’s daddy, who demanded, “Why’re you doin’ this to your mother?”

After that, the folk singer stuffed the bare essentials into ’er backpack an’ guitar case, an’ early the next mornin’, before her parents were up, she started hitchhikin’ west after that start-of-the-world siren call she could hear on every beat of ’er heart.

The blazin’ heat griddle-pressed the folk singer between the naked sky an’ the bakin’ desert.

The folk singer wasn’t a stranger to heat and heat wasn’t a stranger to the folk singer, but walkin’ along the empty, unendin’ stretch’f deadly highway waverin’ off into dreams on the horizon line, she felt compelled to write a song about a Mexican boy makin’ his exodus to the States for a job, a future, an anything.

Sat between two restin’ tumbleweeds, the folk singer worked out a few lines on ’er guitar, playin’ for a lizard that maybe was dead already, but in any case made a patient audience.

She was just finishin’ up when a big rig came glistenin’ and wobblin’ into view. The folk singer zipped ’er guitar away, leapt up from the searin’ dust, an’ stuck out ’er thumb. The truck squealed to a stop alongside ’er and sat there grumblin’. The window rolled down with a cool sigh of AC air.

“What the hell’re you doin’ out in this heat?” the truck driver demanded. “Get the hell in here!”

The folk singer got the hell in, sittin’ ’er guitar upright between herself and the truck driver, a gruff older man with a long gray beard and a Denver Broncos cap he must’ve had since he was knee-high to a rattlesnake. It prob’ly used to be orange an’ white, but he’d smudged an’ smeared an’ faded an’ stained an’ worn it down to a dirty brown, and nothin’ more.

“There’re waters in that cooler under your feet,” the truck driver said, rollin’ the window shut and crankin’ the AC even colder. The truck chugged forward again. “Drink somethin’, for God’s sake.”

“Thanks kindly.”

The folk singer guzzled a bottle an’ a half before either of ’em said anythin’ more’n that.

“What the hell’s a kid like you doin’ out on the road?” the truck driver asked. “You could get yourself killed.”

“I know,” said the folk singer. Her daddy’d told ’er all about that: the world ready to maim an’ kill an’ worse ’er at every turn.

“Where’re ya from?”

“Virginia.”

“No kiddin’.” The truck driver shook his head, tilted back the Broncos cap. “What the hell’re ya doin’ out here in Nevada?”

“Hitchhikin’ west,” said the folk singer.

“What the hell for?”

“It’s what I gotta do, that’s all. If I came from California, I’d be hitchhikin’ east. It ain’t the destination. It’s the exodus that grows ya.”

The truck driver furrowed his gray caterpillar brows at ’er, with a frown in ’is forehead and another in ’is beard. “Who the hell are you?”

“I’m a folk singer,” explained the folk singer.

“A folk singer?” The truck driver laughed only once, but it was a real laugh. “Never in my life heard that one before. I guess I used to see people bein’ folk singers—y’know, Bobby Dylan an’ them—but never in my life did I ever pick up a kid on the side of the road hitchhikin’ west to be a folk singer.”

“Bob Dylan once told a guy from Time he wasn’t a folk singer at all,” said the folk singer.

The truck driver laughed an’ scoffed in one smoker’s-lung sound. “Dylan said a lotta things. He was prob’ly so high he couldn’t see the ground—what d’ya expect?”

The folk singer shrugged all unsure-like, though truth be told, she hadn’t felt unsure about a damned thing since leavin’ home.

Folk singin’ wasn’t for everyone, an’ everyone wasn’t for folk singin’, but it was her vocation to be the voice’f the voiceless, and who else was or wasn’t one of ’er own kind never bothered ’er to think on. The folk singer’d learned an’ grown from the sweet lyrical waters’f Bob Dylan, Nina Simone, Jerry Garcia, Cat Stevens, Janis Ian, Leonard Cohen—were they folk singers? All of ’em? None of ’em? She didn’t know and it didn’t matter. She was a folk singer, in any case, an’ she played what she played, an’ whoever listened? Well, they listened. Or they didn’t. Either way, she played. Either way, she was a folk singer.

“Where’d ya get your hat from?” asked the folk singer.

“Huh?”

“Your hat,” said the folk singer, pointin’ to the Broncos cap. “Where’d ya get it from?”

“Oh, this ol’ thing’s from way back when.” The truck driver adjusted it again on ’is head. “Got it from my best friend for my birthday, a month before he got killed in a car accident. Jus’ sixteen years old. Broke all our hearts.”

“Sorry,” murmured the folk singer.

The truck driver shrugged, eyes on the highway’s ripplin’ pavement. “Ya know how people talk of signs an’ stuff?”

“Oh, yeah.”

“Believe in that sort’f thing, yourself?”

“I do indeed.”

“Well,” the truck driver began with a sigh all sad, “I wore my hat that Sunday after the funeral, an’ the Broncos won when no one thought they would, an’ dumb as it prob’ly sounds, I felt like it was my buddy who did it. Could practically hear ’im cheerin’. Sayin’ how the rest of the world—me included—shouldn’t all come to a stop just ’cause he died. Y’know? So I can’t bring myself to get a new hat. First off, it wouldn’t be as lucky.”

“No,” agreed the folk singer. “I don’t think it would be.”

She pulled a little notebook out of ’er pocket. The edges were worn soft, curlin’ up the way she’d rub at them in thought, under pressure, out of habit. She scribbled some new verses with a stub’f a pencil she’d picked up off a mini golf course in Illinois. She hadn’t paid for a game, but figured it wouldn’t hurt if jus’ one pencil went missin’ from the box by the scorecards. The folk singer never took anything that’d ever go missin’ to anyone’s mind.

“What’re ya workin’ on?” the truck driver asked, peerin’ over at ’er.

“A new song,” the folk singer told ’im.

“What about?”

“Lucky hats,” murmured the folk singer. “Signs. People.”

The truck driver took ’er as far as San Bernardino. Then ’e said she had to get off there, at the gas station, before ’is boss found out about ’im givin’ rides. The folk singer thanked ’im for the lift, the company, the waters an’ Little Debbies an’ potato chip snack bags she’d eaten along the way.

“I don’t have any money to give ya,” she said, “but if ya want, I could play ya a song.”

She fixed the harmonica brace around ’er neck and tuned ’er guitar, which’d suffered its own troubles in the unrelentin’ heat of Nevada. She fit ’er capo in the first fret an’ got ready to play ’er new song about the lucky Broncos hat and its touchdown-cheerin’ ghosts.

“Billy was a big fan of The Grateful Dead,” the truck driver said, leanin’ tired on the side of his truck while it drank an’ drank. “Never got it ’til after ’e passed away. Then I listened to American Beauty all night long, over an’ over, an’ cried through every damn song, I swear to God. I don’t suppose maybe you know any o’ their stuff?”

“I know ‘Ripple,’” said the folk singer. She knew others, too, but that was the one he needed, an’ she knew it, an’ he nodded.

“Yeah,” he said. Then he smiled a bit. “Show me whatcha hitchhiked all the way across the goddamn country for, little miss folk singer.”

She showed ’im.

By the middle of the song, he was cryin’, tiltin’ his Broncos cap so the shadow of it hid his eyes from the other drivers at the station, all turnin’ their heads at the sound of one lone guitar and its singer cuttin’ in over the traffic.

At the end o’ the song, the truck driver slipped ’er seventeen dollars seventy-seven cents an’ told ’er to get ’erself some real food to eat.

“I wish I could give you more,” ’e said, “but that’s every penny I got on me. Careful out there, little miss folk singer. It’s a tough world.”

The folk singer nodded an’ said how ’er daddy’d told ’er as much. She an’ the truck driver didn’t say thanks. The thanks’d been in the music, in the crumpled bills. He got in ’is truck, an’ the folk singer walked off, alone again, hopin’ to get a ride to San Diego or somewhere.

In San Diego, she set ’er guitar case open in front of ’er while she played in a park by the water. She strummed ’er own songs, tellin’ the stories in ’er head to all the people who walked by with their eyes fixed forward. Kids every now an’ then gave ’er a glance or a grin, but their parents had ’em by the hands, an’ they never got to linger long enough for a full verse.

Midday came, guitar case empty.

The folk singer took a break, nappin’ under a tree with ’er arms an’ legs wrapped around ’er guitar, and ’er backpack under her head for a pillow, and ’er jacket lyin’ over her face to block the sun winkin’ between the branches.

When she woke up, she ate the leftovers of ’er lunch and started playin’ again.

The folk singer told the ducks in the water about a pastor who prayed every night an’ every day, hands a-clasped before his rollin’ eyes so sad, for all the poor hungry an’ hungrier little children of the world to eat an’ drink, please, O merciful God. She told ’em ’bout a thin-faced girl comin’ up to the pastor durin’ his lunch break, hands cupped out in the image of another God’s-people’s prayer—Please, Father, I’m hungry an’ my little brother’s hungrier—an’ how the pastor dropped to his knees right there before the girl an’ God an’ asked for mercy please to feed these children.

The ducks quacked an’ went away.

The folk singer thought maybe she needed to lighten up a bit on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, so started singin’ a different song. This one was about a dog who chased its tail up the street an’ down it an’ across the whole town an’ even ’round the world itself, ’til ’e finally caught the ratty thing in ’is teeth and realized it wasn’t ’is tail at all, but the tail of a kite somebody’d let go. Turned out the dog didn’t have no tail at all to speak of—just a little stump of a thing he couldn’t even turn around enough to see.

A couple walkin’ arm-in-arm stopped to see what the folk singer was doin’.

“What are you doing?” the girlfriend asked.

“Singin’ folk songs,” said the folk singer.

“Folk songs?” the boyfriend asked.

“I’m a folk singer. It’s what I do.”

“Just like Joan Baez,” the girlfriend said admirin’ly. The folk singer had to squint against the glare of ’er white teeth. “Do you know ‘Diamonds and Rust’?”

“I sure do.” The folk singer positioned ’er fingers over the fretboard—but the boyfriend cut ’er off.

“I used to like Johnny Cash back when I was in middle school,” he said.

His girlfrien’ tilted ’er head at ’im, an’ the folk singer watched the hypnotic sway an’ sparkle of ’er danglin’ silver earrin’s. The girlfriend said, “He wasn’t a folk singer. He was a country singer.”

“Babe, it’s the same thing,” her boyfriend said. Then, to the folk singer: “Do you know ‘I Walk the Line’?”

“Sure.” The folk singer repositioned ’er fingers, but the couple walked away arguin’ about folk music an’ country music an’ whether they were the same or different, an’ what exactly constituted “folk music,” anyway?

To the folk singer’s mind, it was music by the folk for the folk. And just who were the folk? They were the ones noddin’ along. They were the ones who got it. That was all. Nothin’ else mattered, did it?

The folk singer went back to playin’.

An angry man came up to ’er soon after. Why ’e was angry, the folk singer couldn’t’ve said. She thought maybe he was angry at the world in general, an’ all the creatures livin’ in it—angry at ’em ’cause they weren’t angry, too—so she tried switchin’ into a cheerful sort’f tune that might cool the flush from ’is cheeks. He only waved for her to shut up.

“Just what,” he demanded, “are you supposed to be?”

“A folk singer,” said the folk singer.

“There is no such thing as folk singers anymore,” he informed ’er, with indignation.

The folk singer glanced down at herself. She raised ’er brows, mostly to be sure there wasn’t a unicorn horn sproutin’ between ’em, an’ then she said, “There’s plen’y of us. Somewhere. Prob’ly.”

“Folk singers?” he demanded. “People who would call themselves folk singers?”

“If ya asked a cat what it was,” said the folk singer, “wouldn’t it meow?”

The angry man allowed suspiciously that yes, indeed, a cat would prob’ly meow if interrogated.

“An’ wouldn’ that sound be answer enough for ya?” asked the folk singer. “Or would ya say it wasn’t a cat after all, ’cause it didn’t exactly say as much?”

The angry man scoffed an’ stormed away without givin’ so much as a penny to the still-empty guitar case. The folk singer considered makin’ a sign that said, MUSIC’S BY DONATION. QUESTIONS $5 EACH.

But so it went! So it went. She faced ’er way towards ’er pers’nal sun again, an’ she carried on playin’ the song she’d wrongly thought could make the angry man less angry.

She turned ’er head side to side along the harmonica, tappin’ ’er foot along with the beat, an’ told anyone listenin’ about a man who found a shortcut to Timbuktu—just aroun’ the corner, behind the buffet, in the dumpster where the scraps o’ the day went to—

The soda can wasn’t even opened or empty when it hit the folk singer straight in the side of ’er head.

It knocked ’er off on the toes o’ one foot, spinnin’ the world an extra mile a second an’ cuttin’ ’er off in the middle of ’er verse.

“Get a job!”

It rang through the park, ducks all quittin’ their bobs for food, birds all pryin’ly turnin’ their ears in the trees. The folk singer’s head was a rung bell still ringin’. She put ’er hand up to where the can hit an’ didn’t find any blood or bone stickin’ out where it shouldn’t. All was well, then, an’ now she had somethin’ to drink later. Serendipity.

The folk singer didn’t turn around. She didn’t care or wanna know anythin’ about the face of somebody who’d do such a thing. They belonged where they were: nowhere.

Her guitar pick’d snapped in half, though. She dug a different one out’f ’er pocket and went back to playin’. The yolk o’ that hard crack came out in a new song, which the folk singer wrote straight onto the air an’ titled “Giving Violently.”

In it, a man got stabbed in the heart, when all ’e ever asked for was a letter opener to get ’is bills paid.

The police came aroun’ sunset an’ asked the folk singer to please leave.

They were polite enough about it that the folk singer agreed she’d get out’f everyone’s hair, but what she didn’t tell the boys in blue was she’d be right back there the next mornin’ with other songs to play. She had a livin’ to make, after all.

But since the livin’ hadn’t been so high-rise for her that day, she needed to find someplace free to sleep for the night.

She wandered through the city, watchin’ the fallin’ sun lose ground against all the dazzlin’ lights of the skyscrapers an’ hotels, an’ all the hundreds’f cars tracin’ temporary scars’f radiance between ’em. The folk singer felt so far apart from it all, she couldn’ even find a way to write a song about it.

She thought’f ’er mama an’ daddy. She wanted to call ’em an’ say how she made it to California, but she didn’t have a phone, an’ the coins jinglin’ in ’er pocket were for gas station breakfast, lunch, or dinner—an’ she could only choose the one.

She might’ve been able to send ’em a letter instead, at least to assure her daddy the world hadn’t maimed or killed or worsed ’er. She hadn’t been picked clean by vultures in the desert or kidnapped by gangs in the cities. She was alive, which was about as much as anyone could ask for. An’ she could tell ’er mama she was sorry, too. That she was runnin’ after, not away, somethin’ maybe she should’ve said before she left in the first place.

But she didn’t have an envelope or a stamp or even any paper besides the notebook she’d already filled up with ’er dreams an’ their rhyme schemes. So the folk singer had no way’f tellin’ ’er parents anythin’, from hello to goodbye to all the sorrowful unsaid sorrys between ’em.

The folk singer made ’er way to the outskirts of the city, where all the other nothin’-holders clung on close as they could, held at arm’s length by the everythin’-holders livin’ in spittin’ distance of the stars. The folk singer tried to spy into their windows, just outta curiosity, but they were too high up off the ground she walked.

Her guitar weighed heavier in ’er hand. She switched it from one side to the other, but it never got easier for it.

A little while later, the folk singer stepped into the light of an oil-drum fire—a heap’f trash an’ rags an’ God-knows-what burnin’ an’ collapsin’ on itself under a set’f dirty hands.

The homeless man glanced up at ’er, fire-eyed but mild all around it. Careful, like she might spook, ’e said, “Hey. You in the same boat?”

“I think I am,” said the folk singer. “Never been before, but I am now.”

“When’s the last time you ate?” The homeless man glanced around at his torn-up backpack an’ rag blanket, piled together in the weeds against the wall of an abandoned factory. “I think I might have something left, if you—”

“I’m not hungry,” the folk singer lied, ’cause she never took anything that’d ever go missin’ to anyone’s mind. “I jus’ ate not so long ago.”

“Well, come join me, anyway,” said the homeless man. He moved aside, as though to make more room around the fire, as though it weren’t a perfect circle an’ ’e weren’t just goin’ around it. “What’s your story? If you don’t mind me asking. You’re just real young, is all.”

“I wanna be a folk singer.” She set ’er guitar case in the gravel an’ rubbed ’er hands over the cracklin’ breath’f the fire.

“Wow,” said the homeless man. “What made you wanna do that?”

The folk singer shrugged. “Same as what makes me wanna breathe every day.”

The homeless man smiled so beautifully at that, all crinkles around the eyes an’ a twinkle in ’em from the gold of the fire. “Well, go on, folk singer.”

The folk singer lifted ’er head an’ looked at ’im, returnin’ the smile halfway. “You wanna hear a song?”

He held ’is dirty hands out to say, Go on, again, an’ so she took out her guitar, retuned it, an’ fit the harmonica brace around ’er neck. She asked, “What d’ya wanna hear?”

Now it was the homeless man’s turn to shrug. “What d’you got, folk singer?”

The folk singer shuffled ’er feet in the lonely, dusty stones. Leavin’ ’er capo in the case, she slipped the pick into ’er pocket and used ’er fingers to strum, soft for the night an’ the sleepin’. She breathed ’er story outta the harmonica, whisperin’ the music as quiet as it would go, nothin’ but a dream on the tired night air, dancin’ aroun’ the fire an’ all high up to the stars without stoppin’ at any windows along the way.

The folk singer sang about roads that went on forever twice over, straight off the edge’f the map, straight into the blue an’ wide emptiness packed at every turn. She sang about gettin’ lost, the first step’f gettin’ found, an’ how no one ever in the world had nothin’, not really.

The folk singer sang about the stars over their heads, an’ how maybe they were dead already, or maybe they weren’t—but look at ’em twinklin’, look how beautiful, what’s to stop ’em?

“Yeah.” The homeless man nodded, one knee dancin’ to the beat’f ’er tune. “That’s it.”

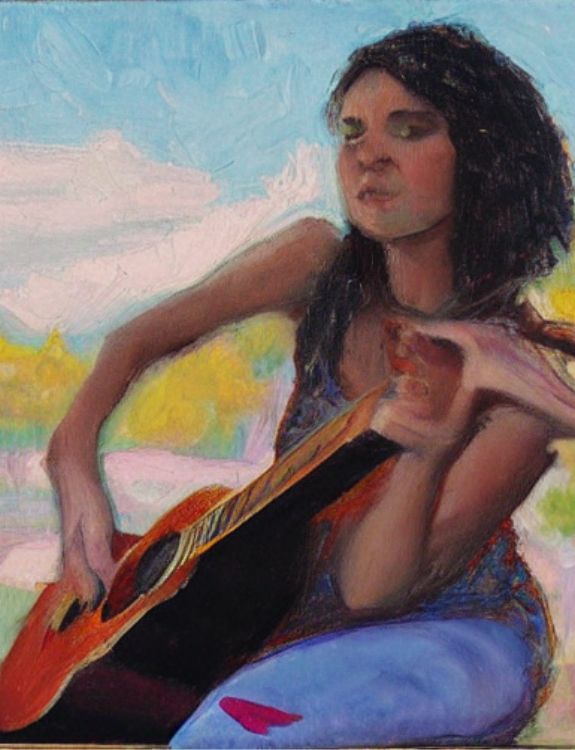

Image: Image created with Stable Diffusion AI, prompt provided by Portland Review.