In the spring of 1983, Russian choreographer George Balanchine, at the age of seventy-nine, lay dying of a rare neurological disorder in Roosevelt Hospital. According to his biography by Bernard Taper, dancers from the New York City Ballet, the company Balanchine founded and spent a lifetime nurturing, came by to visit in dribs and drabs, for he had been there for many months. Not only the one hundred or so dancers that were in the company at the time, but also many retired dancers he had worked with throughout his life came to pay their respects. In his last weeks he was troubled by nightmares, and increasingly weak and confused, speaking in his native Russian to American friends he failed to recognize. But dance was still foremost in his mind. At one point, Maria Tallchief, one of his many former ballerina wives, stopped by to find him propped up in bed, quietly studying his moving fingers. “I’m making steps,” he told her by way of greeting. The mind that created over four hundred ballets continued to churn as it always had. On another occasion, Jacques d’Amboise and Karin von Aroldingen, now middle-aged, happened to visit at the same time. Forgetting that d’Amboise had long since retired, Balanchine requested they begin work on a Vivaldi Chorale he was creating for them. Touched, they attempted to intuit his wishes, improvising a make-shift pas de deux, like those they had danced in days gone by. They began to intertwine their arms and steps in the tiny hospital room for a few moments before becoming too emotional to continue.

Maureen Dowd, reporting for The New York Times, happened to mention in her descriptions of Balanchine’s hospital days that one afternoon Joseph Duell, a principal dancer in his mid-twenties, stopped by the hospital between rehearsals. Finding his mentor alone, the young man asked Balanchine to solve a riddle that perplexed him; it was a riddle of his own making, (since most dancers don’t bother about such things). Why, he asked, had fifth position held such unquestioned primacy in classical ballet for over three centuries? I sometimes wonder what sort of answer Duell was looking for: historical? technical? philosophical? Perhaps he wasn’t really expecting any literal answer at all. Balanchine was a man of metaphors; his metaphors usually made sense to dancers, but not to the frustrated journalists who interviewed him. He also discouraged intellectualism in his dancers, feeling it would destroy the music-driven spontaneity that was central to his aesthetic. On rare occasions when they happened to ask about their roles in his abstract ballets, his oft quoted advice was, “Don’t think, just dance.” On this particular afternoon, Balanchine had not forgotten that Duell not only brooded more than most, but also suffered from bouts of depression. Instead of answering his disciple’s riddle, Balanchine gave him advice, “You know,” he said, “I wouldn’t worry. Just live.”

*

Just dance. Just live. Both easier said than done.

I know because I was a student at the School of American Ballet in the five years leading up to Balanchine’s death, making me among the school’s last generation of dancers to be trained during his lifetime. Balanchine founded the school in 1934, shortly after accepting Lincoln Kirstein’s invitation to come to America to build a ballet company that could rival Europe’s companies. Kirstein, just after becoming a newly minted Harvard graduate, discovered Balanchine while traveling in Europe where the young Russian choreographer had begun to make a name for himself choreographing for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe, the most famous ballet company in the world at the time. He and fellow dancers had joined the company in 1924 after fleeing the newly established Soviet Union. Under Diaghilev’s aegis, Balanchine had the opportunity to work with other young, talented modernists including Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, who were among the avant-garde artists creating costumes and set designs, and composer Igor Stravinsky, with whom he developed a life-long relationship of artistic collaboration and friendship.

During the eight months that Balanchine was hospitalized, we students were blissfully unaware of how sick he was. Entering the still-quiet dressing room on May first, early in the morning of the opening day of our annual spring workshop performances, I was genuinely shocked when a fellow student stopped brushing her hair to ask in a breathless voice, “Have you heard? Balanchine’s dead.” For a split second I thought maybe she was lying or telling a lame joke, but almost in the same instant the large, stately pair of ceramic vases of seemingly festive flowers that I had just passed in the lobby registered their true meaning.

To the dancers with whom he worked, Balanchine was both a god and a man. For us, he was God, pure and simple. Though we rarely saw him, we felt his presence everywhere. His teachings infused every movement we were taught in class, from the proper timing of a battement tendu, to how to delicately curve our fingers to suggest flower petals. We weren’t brainwashed. Or if we were, we were complicit in the process because we could, and did judge for ourselves, sitting alone in the dark theater a couple of times a week. You can be a thirteen- year-old bunhead and recognize genius when you see it. We were delighted, moved and amazed by the ballets, so they naturally encompassed everything we aspired to. It didn’t matter that Balanchine only visited the school a few times a year—in fall to select a precious few from the advanced class to join the company, and in spring to observe the final workshop rehearsals, which of course, required his blessing. Sometimes you would be lucky and pass him on the sidewalk in the Lincoln Center area we all frequented, anywhere between his upper West Side apartment and the New York State Theater. Depending on the season, he wore an old-fashioned Austrian suit, topped off with a short silk scarf knotted at the side, or a long, wool winter coat. He always held his white-haired head, with its prominent forehead and receded hairline, much too high to notice anything beneath the promontory of his nose, certainly not a mere student. Every fall he chose a lucky few to join the company, usually from among the select favorites our teachers offered up on a sterling silver platter—but sometimes he surprised everyone, most often by not taking a cherished favorite, but in some extremely rare instances someone the teachers had overlooked. Suddenly this person was seen, by everyone, in a whole new light. Such anomalies were enough to give the rest of us hope (though they shouldn’t have). Balanchine’s death seemed impossible to our generation, for one simple reason: our dreams, which were more important than anyone else’s, had not yet had the chance to come true.

*

I was living in Pittsburgh when, three years later, the dance world was rocked by the news that Joseph Duell, at the age of twenty-nine, had jumped to his death from the fifth story window of his West 77th Street apartment at 10 a.m. on a Sunday morning. He left no note, and though it was known he had long battled with depression, and The New York Times mentioned that he’d been under the care of a psychologist and psychiatrist for several years, the dance community was nevertheless stunned as well as saddened. At the time, I was suffering from depression myself. I’d moved back home after having to turn down my first professional contract because I had torn the metatarsal ligaments in my right foot. Then it became evident that my foot was never going to heal fully, that dancing was over for me.

When I heard about Duell, I was not entirely surprised. While a student, I had heard stories that trickled down from the company about his depression, including his painful breakup with his longtime girlfriend, a fellow dancer with glimmering red hair and long, white lyrical arms. Not knowing any of the actual details, I imagined that she must have been forced to disentangle herself from the tentacles of his depression, so vulnerable (I was learning from painful experience) is every psyche that, unfortunately, the unhealthy mind threatens to envelop and pull down the healthy friend or lover, rather than the other way around.

That Duell made his fateful decision in February also provided some explanation, at least for me. Even now, more than thirty years later, I do not forget Manhattan in late winter. A time when long sidewalks, impassive apartment buildings, and blank sky become one oppressive mono-sphere of gray, a world in which all the color has bled out. Until I lost my dancing, which gave my life purpose, I’d been down before, but I’d never experienced the painful confusion that comes with a more tenacious depression: confusion about who you are, about where your sense of hopelessness comes from, and why even those closest to you cannot help shoulder the burden. I knew all too well that when a person is depressed, nothing seems more elusive than to just live. Still, even as low as I felt then, (fortunately, the worst I’ve ever felt for a prolonged period of time), I had never contemplated suicide, so I knew that Joseph’s suffering was much more immense than I could imagine or understand.

But as someone grappling with no longer being able to dance, and envying as well as admiring Duell’s success, another part of me was not only dumbfounded, but resentful at his decision to take his own life. How could someone like him feel hopeless? I recalled how all of us at the school adored him. Admittedly, a large part of it was his sex appeal—he was tall, handsome, with light brown hair, large green eyes, long, muscular legs, and a boyish smile. His youthful charm was enhanced by his being the little brother of Daniel Duell, who also was a principal dancer in the company. Both were among the few straight men in the company, and both, besides being respected and well-liked by their peers, had a down-home quality, rather than the arrogance so common in successful male ballet dancers. With all this going for him, Joseph was the object of many a school-girl’s eye. Despite the complexity of his psyche, he had the easy air of the kind of guy you hoped to meet when you went home in the summer, the kind you imagined would drive you around in his first car and teach you the ropes. That was his appeal offstage. Onstage, he wasn’t the type to dazzle you with flashy, macho tricks, which didn’t come easily to him; instead, he was clean, sweetly proud, and unexpectedly elegant—in short, the perfect choice to wear the gold-embroidered white tunic and play the young prince. An unusually attentive and able partner, he was well-paired with, and favored, by ballerinas of every age and stripe.

A few months after Duell’s death, fellow New York City Ballet dancer Toni Bentley wrote that he had taken every dancer’s obsession with perfection to the ultimate extreme. A perfectionist among perfectionists, he was fiercely devoted to correcting his flaws. He woke up early to attend exercise sessions before going to morning class, and after class he continued to practice the combinations that had been most difficult for him. Equally disciplined about caring for his body, he rigorously maintained a healthy diet and refrained from drinking and smoking.

Bentley’s portrait of Duell reveals he was more intellectual than most dancers, or at least more verbally so. Besides choreographing ballets for the school, he coordinated the Ballet Guild’s luncheons and family matinee programs, giving lectures in which he would dance and speak about the history and language of classical ballet. Unlike most dancers, he felt the need not only to brilliantly execute the intricacies of classical ballet technique, but to ponder and explicate them.

People close to Duell were concerned about him in the weeks before his death because he seemed tense, agitated. Still, as late as the day before, his behavior didn’t raise any alarms. Bentley recalls that earlier that day, she had enjoyed Duell’s matinee performance in “Symphony in C”; that he had danced beautifully, perhaps more so than ever before. Later that evening he had given his all while rehearsing “Who Cares?” going over his variation repeatedly, asking fellow dancers each time if that time had been better

*

It’s been many years now and still Duell’s death plays tricks with my mind, somehow inviting my envy and admiration to extend, irrationally, to his suicide. Unable not to admire him, I can’t quite convince myself that he didn’t somehow miraculously solve the dreadful problem of death on his own terms; that he didn’t leap into an unknown stratosphere, or step through a cosmic portal that allowed him to shed the prison of his body and all its inevitable imperfections, including its terrifying expiration date. His act brings to mind the title of Suzanne Farrell’s memoir, Holding on to the Air, which evokes the sometimes desperate desires of dancers to become ethereal. When I think of Joseph’s death, I only briefly envision the unforgiving pavement and other horrifying images one usually associates with suicide, before my mind hangs a left and rises, swept up like a leaf caught in an air shaft. I see Joseph sitting motionless on the couch in the living room of his apartment, contemplating fifth position’s primacy of place in ballet’s vast geometry—the lines, the circles, the radiance of it—long into the night. I see him having some sort of revelation at the first hints of dawn, sometime after the city street below his windows has gone completely quiet. Resolved, clear-headed, relieved, he falls asleep about four, his breathing calm, peaceful. Rising in late morning, he listens in silence to time, and just at the moment morning anticipates noon, he walks slowly, quietly, elegantly across the room, throws open his window to the cold February air, deftly finds his footing on the window ledge, and steps into the light.

*

Fifth position sits at the center of the classical ballet grid—its crown jewel, embodying and signifying perfection. Famous dance critic of The New Yorker Arlene Croce wrote that Balanchine was one of the few people to understand fifth position’s transcendent power to unlock space. “Balanchine’s ballets were meant to project from deep inside the cubic space of a classic opera-house stage. That’s why the tight fifth position is so important; it unlocks the body’s ability to occupy and animate space in depth.” Lamenting the sloppiness that had seeped into the New York City Ballet’s performances since his death, she explained, “If Balanchine had any secret, it was one that has endured through two hundred years of classical ballet. It is that dancing correctly in three dimensions, on the music, creates the fourth dimension of meaning.”

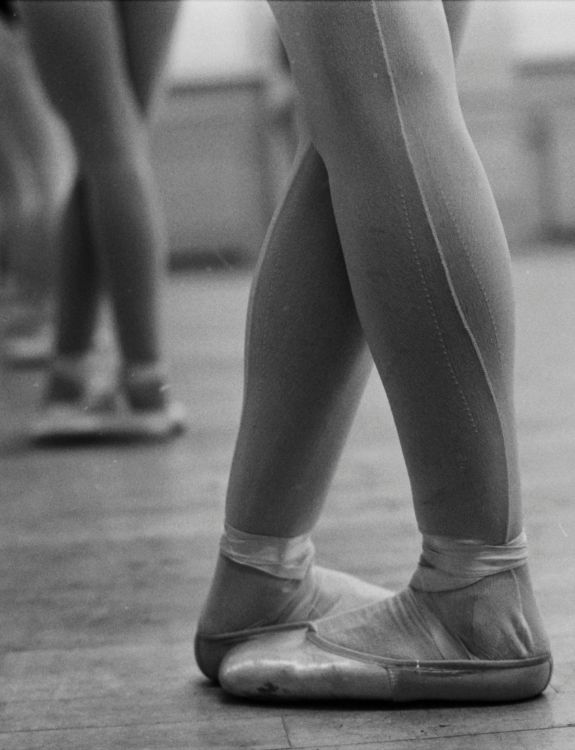

To execute fifth position requires, like most ballet movements, “turnout:” the legs, from the hips down, rotate outward rather than facing forward the way we stand naturally. The dancer uses the muscles of the inner thighs, rear, and core to rotate the legs one-hundred and eighty degrees, so that in first position, the heels are placed against one another while the toes face outward to form a straight line. Fifth position operates like a vice, requiring you to squeeze your inner thighs ten times more than in first and fully rotate the muscles all about your hips, completely flipping them inside out, all so that your front heel can cross in perfect alignment over the inside of the big toe of your other foot, while the inside of the heel of your back foot, tucked up against the little toe of the front foot, holds the cross in place.

Fifth is no position for amateurs. Recreational dancers fall back on third, which crosses the legs much more forgivingly, only half-way. Serious dancers, however, can hardly bear to even look at third because it’s really just a shamefully sloppy fifth. When novices attempt fifth, say, standing around at a party with drinks in hand, mere standing, for most people, drunk or sober, becomes a challenge. Usually, they’re unable to keep their knees from bending or their legs from sliding back to the normal, forward-facing position of our species. Their entire bodies appear contorted; even their arms behave strangely, stiffening and turning out sympathetically, palms twisted upward, as if in supplication.

Cross your fifth, is something every dancer in training is told day in and day out because your legs tend to betray you by relaxing ever so slightly, leaving the tip of your back toe sticking out, like the fallen hem of a dress. In fact, you could probably blame fifth position for most of the innumerable injuries that plague dancers, and eventually end their careers. Occasionally they fall and tear something like I did, but more often it’s the much less dramatic daily grind of fifth, and the immense number of movements that are an extension of it, that give the joints such a terrible beating, eventually requiring dancers to replace hips or undergo surgery on their backs, knees, ankles, feet.

One of the reasons fifth position does so much damage to the body is because it functions as the dancer’s home base. First, most every barre and center exercise starts and ends in fifth. Then, some of the most difficult steps, like pirouettes and tours en l’air, are done starting or ending, or starting and ending, in fifth. A favorite combination of my school days was a series of thirty-two jumps in fifth position, the feet still crossed but now pointed in the air, traveling along four diagonals, one every eight counts—two traveling forward toward the front corners of the room and two traveling diagonally toward the back corners. On the last count you ended exactly where you started having traced a diamond in space. Like baseball, our American teachers liked to say.

Despite its brutality, no dancer would seek to abolish fifth position’s sovereignty. It would be like pretending the sun does not exist.

The positions of the feet in classical dance did not officially materialize until the seventeenth century when King Louis XIV, who loved to star in the ballets presented at his court, commanded his renowned dance master, Pierre Beauchamps, to codify the movements, which is why all ballet steps have French names. Even so, the ethos of ballet’s language harkens back to the ideals of the ducal courts of Italy, where it originated during the Renaissance. The essence of ballet’s logic arises out of the same ideals that inspired Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous drawing of the Vitruvian Man, which he set down in his notebooks in 1490. Inspired by the ideas of the ancient architect Vitruvius, Da Vinci drew an ideally proportioned nude man in two positions, one superimposed over the other and encompassed by both a circle and a square; depending on the extension of the man’s arms and legs, the tips of his fingers and toes precisely meet the lines of either the circle or the square. The man’s navel is situated at the center of the circle. The geometry inherent in the human body, Da Vinci wrote, doesn’t end there: “If you open the legs so as to reduce the stature by one-fourteenth and open and raise your arms so that your middle fingers touch the line through the top of the head, know that the center of the extremities of the outspread limbs will make an equilateral triangle.” Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man beautifully reflects Renaissance conceptions of the human body—its proportions and movements—as representative of, and in harmony with, the mathematical order and majestic beauty of the cosmos.

There is tremendous liberation in the abstraction of the body. The basic movements of ballet, especially the most foundational—plie (to bend the legs to gather power), tendu (to stretch the legs to form straight lines)—are executed the same way and with the same frequency by men and women. Like math, like geometry, they transcend gender. It’s only after steps are stylized by a choreographer that they take on characteristics that may be recognized as feminine or masculine.

At the center of this order, fifth position, like the circle, has no end. The crossed legs form a sort of vertical figure eight, creating a closed system of energy that runs continuously down the front leg, across the horizontal plane of the locked feet, up the back leg, and across the horizontal line of the hips, ad infinitum. Beginning or ending an exercise in fifth, you hold your arms, en bas, just an inch or so in front of you, your elbows rounded gently and your palms turned up toward your face, crowning the vertical line of your torso with an elongated circle, one of myriads of elliptical and circular movements mirroring the revolving bodies of our universe.

To cross your legs in fifth is to make a sacred gesture, like a Christian making the sign of the cross. Engaging your core and lifting your upper body, as you take a step forward with one leg and close the other against it, you harness all the energy emanating throughout and around your body. It radiates a profound sense of order, confidence, peace. It provides a sense of spiritual purpose and conviction that many of us are never lucky enough to find. A conviction that, because it gives your life meaning, can’t help but to give your death meaning.

*

During Balanchine’s last weeks, a visitor who stopped by found him lying in bed, peacefully, with his arms held high above his forehead in bras en couronne, rounded as in enbas, framing the face. No doubt, at least in his mind, his feet were in fifth position, and as a devoutly religious man, this would have been, as dance always was for him, a form of prayer. It’s likely that, (as I find I must hope, against all odds, was the case for Joseph, his disciple) contemplating ballet’s universal language gave him the strength he needed to prepare his mind, body, and spirit for death as for a great journey. Perhaps as he prepared to step into the light, into the always beckoning fourth dimension, he knew that his beloved fifth position, in death as in life, was his key to the path home.

Image: Photo by ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Christof Sonderegger / Com L27-0249-0005-0003 / CC BY-SA 4.0, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.