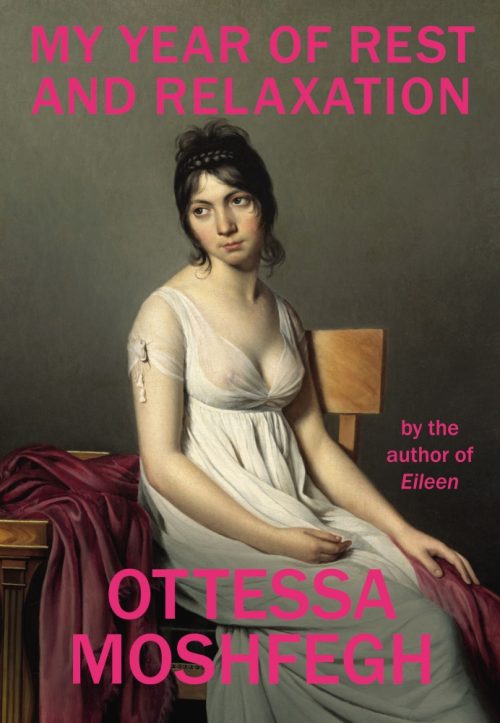

Before opening Ottessa Moshfegh’s new novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Penguin Press, 2018), you might get caught up observing the portrait on the cover. Like many neoclassical paintings of women, Jacques-Louis David’s Portrait of a Young Woman in White is of a porcelain skinned beauty, rosy cheeked and cherry lipped, in a revealing negligee. She sits on a chair, probably in a bedroom, staring off at some unknown point in the room looking supple and elegant and apathetic. Bored. Annoyed maybe. She’s a model woman of her time—inactive—but her eyes betray David’s concept.

Much like the woman in David’s painting, Moshfegh’s unnamed narrator is at rest, but not like the patriarchal model of a woman one might expect from an older generation of art. Moshfegh’s protagonist has decided to induce a year-long “hibernation” with a wide variety of sleep aids and antipsychotics prescribed by a nut-job psychiatrist, Dr. Tuttle. The undertaking of such a task would seem unruly for a character with such a status: she’s young, beautiful, and wealthy enough to stay locked in her Manhattan apartment because of a sizable fortune left by her dead parents. Perhaps the task stems from her relationship with her cold and distant parents whose deaths were only months apart. Or from her noncommittal ex-lover who is embarrassed by their nearly ten-year age gap, but who returns routinely for her beauty and blowjobs. Perhaps it is because of her most recent job at a modern art gallery—the latest installment before she was fired being an exhibition of taxidermy dogs with lasers shooting out of their eyes—that Moshfegh’s protagonist feels she needs to shut off the outside world. Reboot. She is convinced that a year of sleep can dull her thoughts and feelings enough so that, when she wakes, she can start anew.

While My Year of Rest and Relaxation rarely leaves the protagonist’s apartment, the novel is anything but dull. Our protagonist is constantly being bombarded by visits from her friend Reva—a woman envious of the narrator’s ease of wealth and beauty and constantly trying to measure herself against the narrator. Reva is often running to the protagonist’s apartment to escape her own parallel issues: her dying mother, her affair with her boss. The protagonist isn’t as kind to Reva as one might think, and she is often listless to her friend’s troubles or checking off a mental list of Reva’s failed attempts at fashion or wondering how many times she’s forced herself to vomit that day.

There’s also Dr. Tuttle, the protagonist’s eccentric psychiatrist found in the yellow pages. She is often wearing a neck brace for which there is never an explanation. With medical advice that borders insanity, Dr. Tuttle’s quack practice becomes a perfect fit for the protagonist to obtain her vast collection of medications, mostly prescription but some also experimental samples. The protagonist’s attempt to hibernate seems to be going smoothly, but, several months into her task, she hits a snag when she starts to do things in her sleep like ordering lingerie and setting salon and wax appointments—things that she loathes. An unconscious revolt.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation isn’t a single story. If you were to ask, “Is this a funny or tragic novel?” or “Is this story about depression or escapism?” or “Will it be startling or amusing?” or “Will I believe the lengthy lows of human dignity Moshfegh curates?” The answer is yes. Moshfegh’s prose is sharp and direct. Perhaps the most traumatic and strange events in the story are written in the most casual of ways, as if nothing strange were occurring at all, and it could take a few reads over a scene to truly grasp the strangeness.

Moshfegh’s narrator runs counter to social norm and expectation. After reading this story and looking back at the novel’s cover, the woman in the painted portrait seems more irritated than inactive. Perhaps she is waiting for David to leave so she can return to sleep.

—

Peter Zikos is currently attending Portland State’s MFA program and is Portland Review’s Associate Editor.