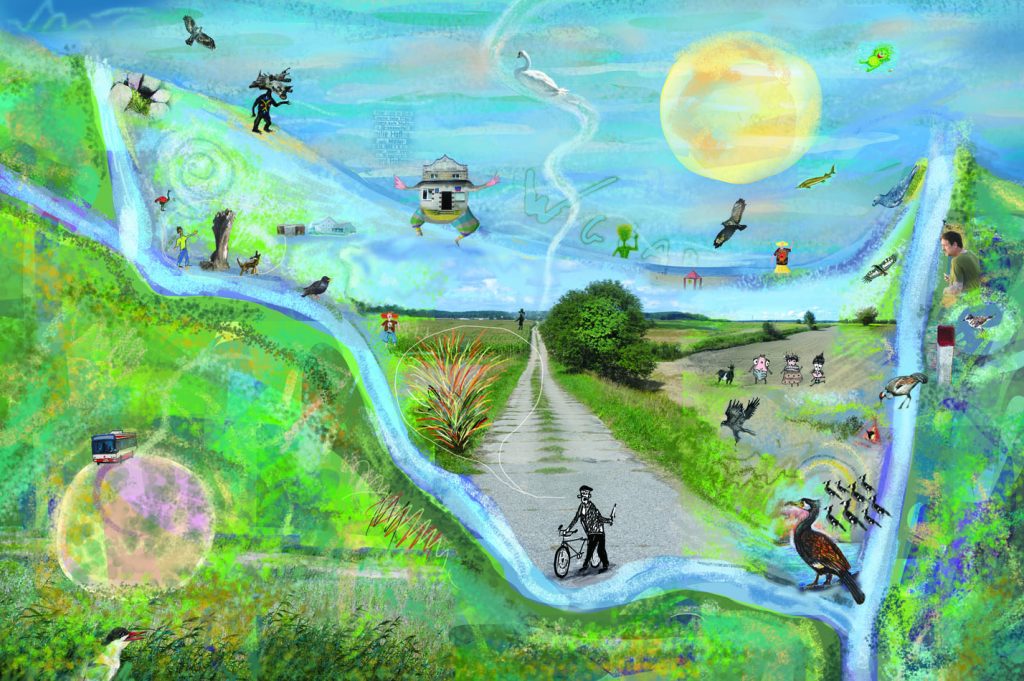

About this project:

In English as well as Polish, the word for the chart of symbols containing information about how to read the map is called a legend. There is more here than just two-dimensional spatial orientation. There are also stories, interpretations, memories. Thus, each little circle representing this little town or that giant city is more than just a fact, but the center of a complex web of connections for the individual who has lived in that place, who has visited that place. And, in every map, there are the blank spaces. Not everything can be represented, not every town, not every house, not every tree—let alone the flying birds and hopping frogs, the women hanging laundry or the men casting nets.

Indeed, one of Jorge Luis Borges’ short stories involves the creation of a map so accurately detailed that it is the same size as the world that it maps. The map is perfect, but also perfectly unusable. Perhaps what Borges wishes us to ponder is that there always must be a gap between what we see and what we can express, between the word and the world. Certainly not just around but also inside the various “maps” of either image and language in this exhibit, there will continue to exist white spaces that other people will be able to fill in, through their own imagination and life histories.

In the early years of cartography, the white spaces would even have a name—terra incognita. Today these blank spaces still remain, though not so much on the edge of our maps, but within their borders as we try to draw in more and more details between the details already present, not to mention the details that are now blurring, caught up in the process of being erased through death, upheaval, accident. Meanwhile, the Map abides, though with continual changes: the story of humanity and the land eternally drawn and erased, raised and lowered, channeled by giant levees and destroyed by giant floods.

Of course, in my poetic mapping of the Wyspa Sobieszewska, I know that I am an outsider. I recognize the irony of a newcomer providing images of this place to those who already live here. My perspective will be different than those of the residents of the island. But while I have been here, I have tried not just to see but to dig, to try to grasp this place not just as it is now but as it has been, to envision the island even before it was an island—created by both ice and Prussian engineer—and to hear the many languages spoken here. In the end, what I have to offer is just another map, though a map where one place is connected to another by image rather than road, where the boundaries are as fluid as the stories.

—Daniel Bourne

Polder Boy

All my life the levees

have been caving in, the Vistula

pouring into my bed, my mother angry at its tracks

she said I made on the floor, the slow meander

to the bathroom and back. In the last century

the man would use a scythe. If he cut his thumb

he sucked it. When the woman burned her bread

she burned it in German. I know this because

I watched them out my window

as they moved through the yard.

(Each night their little boy

joined me in my bed. He spoke his language.

I spoke mine. When we cuddled

we said nothing, our toes

trying to find a shore of warmth.)

The slow flow of cows

lapping at the seawort,

The land puffs like a bedspread

folding upwards at the end.

The tractors

sailing back and forth.

(And then my friend whispers

how one day the Baltic

will rise higher than the sky.

Our bed washing out

into blackness.)

Świbno, Just Before the Mouth of the Vistula River

Sand, brown amber, broken beer bottle,

Pine tree, pigeon, discarded plastic bag,

The smell of fried fish and the small tornadoes of midges

Lifting over the green meadows near the ferry

The moon ascending the truck beds of the delta

Backflow of the river

The whitecaps scattering like gulls

But there are real gulls perched for a ride perched for a ride

There are people riding the bus onward to Przegalina

There are people standing with bicycles people waving their beers

There are cows to the east grazing beside the levee

There are levees grazing both sides of the river both sides of the river grazing

And above the current the terns and black winged swallows

Another river above us with hundreds of feeding mouths

Names

“Pamięc jest droższa od słów (Memory is more precious than words)”

—an epitaph on a gravestone in the cemetery of Sobieszewo

Which is worth more:

the memory or the words of the memory?

Names like Helena Anusiak or Alexander Gajec

like titles on a book

no one will ever read. The names

of sparrow, pigeon and magpie*

frozen in the stones, though the birds

still hop in the branches of the cedars,

celebrate the bugs between the weeds.

The sound of the cars on the nearby street

as they create their own rivers and floods,

their stories written with exhaust.

Eryka Kroll lies here since this Spring

too soon to have a stone, too soon

to be forgotten. Former child

saying Mütterchen or Krümelkuchen.

Unlike the Poles

the words for her fingers

were not the same as for her toes.

Last German

to live on the island. Think

of how her word for death bed

for duck and cloth and river

all were tied up in a sack,

thrown like kittens in the Weischel.

How her precious island of Bohnsak

disappeared into a hole.

*In Polish, Wróblewski (connected with sparrow), Gołębiewski (with pigeon), and Sroka (with magpie), are all common family names. Weischel is Vistula in German, whereas Bohnsak was the German name for Sobieszewo.

Deep Map, Sobieszewo Island

I: The New Polish Lands, 1946

the earth is black enough already, the work

already a raw wound

the grease and mud and smashed fingers

the sound of metal on metal of bone on bone

your teeth jouncing as the harrow scrapes its own rusty path

through the soil

—and then you hit a bomb. once

I looked up to see my friend slide off

the studs of the black rear tire

and then the blood that slid off him.

we never found his arm.

in those days the unexploded shells

lay like hard potatoes in the ground.

sometimes

digging down

you only find more blackness

bones of horses

collapsed tractors

floods waging their own wars

II: Oral History on the Road between Przegalina and Sobieszewska Pastwa, August 2013

first we shot the hawks because there were too many

long tailed fighter planes that strafed the island’s rabbits

the rabbits we could eat

but the hawks were just a flying weed

now you get fined for what was once your duty.

the last time I saw a rabbit

I wasn’t yet such an old man

wrinkles deep

as the ditches in a field

first came the Germans

then the Communists

now people who want to save the birds

each story that you tell

makes an even larger hole

the earth is black enough already

III: Martwa Wisła (The Dead Vistula)

but old men have their uses. I keep my knife sharp

and my tongue even sharper.

but these aren’t just weeds

I cut on the roadside.

dried and bundled

one branch added to another

soon becomes a broom.

we have to sweep the snow

or it will cover us.

the weight of all those drifts.

the weight of all that sky.

IV: Last Remnants

We all become amber. Our faces revealed

in sand.

Deer prints

like angel wings

depressed on the levee wall.

The smeared map of rivers, erasure

and then even more children are born

on top of more children. Once I

opened up our well

and shouted to the bottom.

The echo that came back

was the voice of someone else,

one more mouth of the Vistula

opening like a wound

in the middle of the island.

The Island of Lost Dogs

I.

Bowing, the boxer is shy, front paws splayed

as Ania puts out her own trembling hand

allowing him to sniff her fingers

to show that she too is fragile, easily

bitten or betrayed. That is what they do, those owners

she says, petting the brown mesa of his skull

as the bus arrives, its own sleek body

throbbing like a pent-up canine. November, Sobieszewo Island,

we are to walk the stone causeway the Prussians built,

look for tiny shards of amber. But Ania is clutching

the quiver of this dog, vowing she must take it home.

Leave the mutt alone I think. It’s fat enough to have an owner.

We cannot take a dog on the bus I think. O Ania O Ania.

II.

Island of nurogęs, of mikołajek nadmorski. Who

can argue with Baltic beaches? The sand

balm of summer

healing all wounds? No wonder

that this man or this woman

from Wrzeszcz, Sopot or Gdynia

decides to drop their dog off by the pontoon bridge

before they head off

to the overwhelming winter

of their homes.

All dogs go to heaven.

Even the ones who are too much trouble

“deserve an island home.”

III.

I want to learn the name of every bird I see.

I want to see each seal that returns to the Baltic.

I want to save the environment and drink a lot of auburn beer.

I tell Ania that we can’t take the boxer on our hike.

He’ll scare off all the birds and we don’t even have a leash.

If he is there when we return then we can talk some more.

We all are walking blindly in the middle of a story.

Do you think that as the bus headed off from Sobieszewo to Gdansk,

spewing exhaust and kicked up dust

that the little guy was with us, licking hands and shivering with delight

or was it walking from one street to another,

dark body caught in amber, Ania o Ania, on the island of lost dogs?

Even When There Is Only Ashes (The Fire in the Church, Sobieszewo Island)

“I ask for her favor, and she always brings me such joy, despite her name being the Sad Mother of God.”

—a woman parishoner from Sobieszewo Island, on the Weeping Mother of God statute in the Saletynska Mother-of-God Shrine, the only item saved from the church in the fire of 1960.

Not only war destroys. The fire

in the church, the fire

in the belly of your husband.

Not just the vodka

but the sour pickle of his breath,

the increasing bitterness of tea

when only tears evaporate.

No wonder each woman

carries the woes of the other

through the fire that keeps burning

even when there is only ash.

“When the smoke cleared that night

only the stars were our comfort.

Not even Our Mother’s weeping

could put out the flames.”

But as they dragged her to safety

She also carried them

(their leaking roofs and broken hips

their dead children and drowning husbands)

calling the secret name she used

to soothe them

lost inside the darkness

of their childhood beds.

The Fallow Lands (Ugory), Sobieszewo

How do they contribute?

Tolerate

the bad habits of the river

Reflect the sky

The green minorities

that never get to vote.

Dogs and weeds go there

to hide

until they get their day.

—

Daniel Bourne’s books include The Household Gods and Where No One Spoke the Language. A translator from Polish, he has lived in Poland off and on for many years, including the fall of 2018. Other poems about Sobieszewo Island, Gdańsk, and Poland in general have recently appeared in Salmagundi, Yale Review, New Letters, Diode and St. Ann’s Review. He teaches English and Environmental Studies at The College of Wooster in Ohio.

Wojciech Kołyszko has been a noted book-illustrator and visual artist in Poland for many years. Twice he has won the Polish Association of Book Publishers Award for the best artbook of the year, among other distinctions. Since 2003, he has lived on the Island of Sobieszewo on the Baltic Coast just to the east of Gdansk.