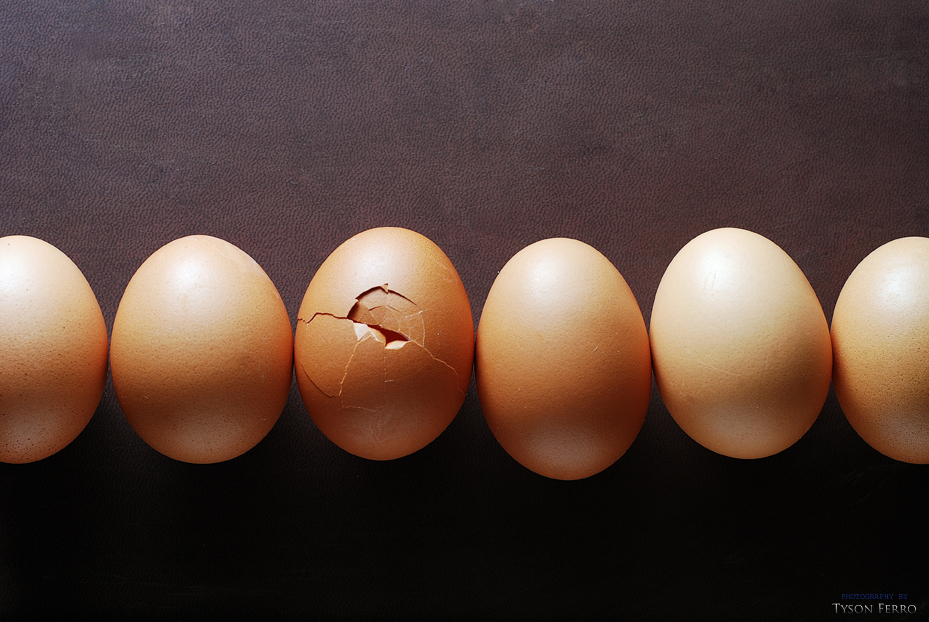

The eggs come out of her mouth whole, one by one. Plain brown eggs, same as you’d buy at the supermarket.

“Does it feel like they’re coming faster?”

Belinda rocks forward at the kitchen table. Her long red hair swings, matted in chunks by whatever product held it in place for our date last night. Mousse, I’d guess, from the powdery smell of it in bed. Her dry lips part and this is the signal it’s coming sooner rather than later. There is a particular sound just before the egg emerges; a wet, collapsing noise. It’s not quite gagging, more like a glottal evacuation. A blockage removed. It’s the kind of visceral sound effect a director might lean on in a horror film, if production doesn’t have the budget to make the gore look like more than ketchup.

“Can you feel it before it’s in your throat?”

Belinda lurches forward, her face paprika-red. The table shudders. The whole process only takes about a minute or two, from gulp to jerk to egg. Initially, I thought the intervals between them might be like contractions, coming closer and closer together until some big, final bang—a whole chicken, feathered and clucking, clawing its way out of her mouth, or a hen roasted and smelling of sage and thyme delivered on her tongue. But so far, the space between eggs has been unpredictable.

“Oh god.” Belinda’s eyes bulge. Egg number ten.

I am not a biologist. I am a high school English teacher. What I know of the body fits well on its outside, and in the simple mechanics of its digestive tract, and in the shape of the aorta, which always looks to me in diagrams like a kind of flute; the pipe Pan plays to trick the body into keeping its spirit. The body and its mysteries, frankly, intimidate me. Deep inside my own body, for instance, in their respective organs, I know that I have eggs, too, but I’ve never seen them up close and am relatively certain they don’t look like this.

I have no more answers for this small, violent drama now than I did two hours ago, when I padded into the kitchen in my boxers and sports bra and got as far as taking down the pancake mix for breakfast. “Oh, god,” Belinda uttered behind and we darted into the bathroom. I held her hair while she braced herself over the toilet bowl I had cleaned in preparation for our third date, dinner at my place. To our surprise, instead of last night’s partially digested linguine, what splashed into the water was the first egg.

She sets the new egg in the carton. The look of pride falls. She is tired.

“And this is the first time this has happened?” I grip the back of a dining room chair, unsure now, as all morning, if I should sit or stand, call an ambulance, drive her home.

“You already asked me that. Yes.”

Belinda lifts the glass of water from the table and finds it empty. “I guess there’s some kind of pressure in my stomach. Or right above my stomach.”

I take the squat green-tinted tumbler from her, one of a set I bought from IKEA at the same time I bought the table, the bed frame, the dish towels, the rugs, the garbage cans, the shower curtain, the sofa pillows, the coffee table, the bookshelves, the colander, the silverware, the pots, the pans, the cutting board, the closet hangers, the lamps, the nightstand and the poster frames. It is reassuring to think of all of these items in their places right now, of their clean surfaces and perfect order. The way they adhere to the prescribed method of the apartment universe is a comfort. “I could make tea, too, you know. Or coffee.”

Belinda shakes her head. “I don’t think caffeine is a good idea right now. Anything that’s a catalyst. It feels like it’s somewhere down here.” She moves her hands over her chest and stomach.

“Maybe we should see what’s inside.”

“What?” Belinda doesn’t hear me over the running faucet. I shut the water, bumping the glass against the handle of the frying pan I used to make pasta carbonara. It disgusts me, leaving dirty dishes in the sink overnight, but Belinda hadn’t been interested in drying while I washed. “The dishes can wait,” she’d said, slipping off her shoes and reclining on my couch. “Do you have another bottle of wine?”

“I said maybe we should crack one open and see what’s inside. It might give us some clue to what’s happening.” They could be sitting there filled with blood. Or maybe this is how the ovary stores its eggs, in larger receptacles that crack open one at a time over the course of our lives to spill out hundreds of opportunities for more life. Maybe these eggs are only enlarged, a form of gigantism. Maybe our reproductive parts are, on a large scale, closer in appearance to chicken eggs than we think.

Belinda shakes her head. “No. I don’t think so.”

Coming close to her again with a fresh glass of water I can smell Belinda’s sweat and her stale, dry breath mixing with the ghost of her lilac perfume. We lay in this scent for hours this morning, watching the sun crawl the wall and trading more stories of all of the life we’ve lived so far, in no rush towards the rest of the day. The eggs were gestating then. Shifting, maybe. Lining up to make their entrance. The way a thing can lurk inside of a person—you just never know.

“Oh god.”

Another egg arrives. Belinda slumps against the chair. I excuse myself to the bathroom and take a series of deep breaths, inhaling the mix of sea breeze plug-in air freshener and Ivory soap. I appreciate order. Clean tiles. Shower curtains free of mildew. Over the years, I have made many silent compromises. I have put up with smokers who leave my pillows smelling like ashtrays. An extreme yoga enthusiast who would come over after class and press her damp, sweaty back against the couch cushions. A woman who would get up before sunrise on a Saturday morning to jog a few dozen laps around the neighborhood before brushing her teeth. And worse. Offenses of taste. Women who hate coffee. Women who hate chocolate. Women who insisted on sleeping on my side of the bed. There is always some quirk to negotiate.

I have a new therapist now, one who sits cross-legged on a fluffy armchair and drinks soda from fast food cups and never writes anything down. She asked me to write a description of my ideal partner, but I know better. There is always some quality you do not count on. I want an element of mystery, I said. An unknowable unknown. My therapist has suggested that, perhaps, I am holding out for magic when love, really, is far more practical than that.

*

I messaged Belinda on the dating site because, well, she looked pretty and seemed happy and smart. I imagined a sort of woman I have dated before, a woman in her early forties who has grown comfort up around her in a one-bedroom apartment like a field of mushrooms that, from afar, has its unusual beauty, but, up close, smells like forest mold.

I was wrong.

On our first date at the better of two Italian restaurants in our suburban downtown, Belinda’s lifted her wine glass when I ordered gnocchi and let out a big laugh that turned heads. “This is the third date I’ve been on this month and the first time the other woman didn’t order a salad. Let’s get married!” The laugh came from the bottom of her, eyes on me across the table, joyful, self-possessed, brilliant.

Belinda is a reference librarian at the community college. “You wouldn’t believe the number of people who want me to show them the Constitution. The real one. Like we have it on a scroll in the back!” We talked about former students of mine who have likely checked out books at her counter, delighted by our invisible synchronicities. We agreed to a second bread basket and shared dessert, our forks spearing the moist chocolate cake in steady, equitable bites until the whole thing was gone and she smiled at me.

“I like your jokes,” she said and I blushed.

After dinner, we held hands on the way out to the parking lot, where she kissed me long and warm on the cheek. It was, by all accounts, a very good first date.

*

“I don’t have great insurance,” Belinda mutters. “ER trips are really expensive.”

“It’s been happening for two and a half hours. We don’t know what kind of fluids you’re losing. And nutrients. If your body is making all of this, you must be depleted of all sorts of things.”

“I need to get home.” She buckles her seatbelt. “God, it’s almost three o’clock. I need to feed my cat.”

“You have a cat?”

“Don’t tell me. You’re allergic.”

“I have pills for it.”

Four more eggs drop in the car on the way to the hospital. We put them in the empty cup holders, the carton forgotten on the table in our rush to leave.

Belinda pushes the passenger seat as flat as its mechanism will allow. “How do you keep your car so clean?” She burrows her hands in the hem of the t-shirt, stretching the NPR logo towards her knees. “Your dashboard isn’t even dusty. My car is full of receipts and coffee cups.”

“Is your apartment that way, too?” Piles of crusty dishes on a coffee table, dirty clothing mixed with clean on her bedroom floor, junk mail spilling across her kitchen counter, all of it covered in cat hair. I shudder.

Belinda closes her eyes. “That never works. Messy and tidy.”

The emergency room parking lot is half-full of carelessly parked cars. I park with my wheels on a yellow dividing line and gather up the eggs in both hands. Belinda charges for the sliding doors, coat billowing behind her, one strong, pale leg thrusting through the slit in the sarong. I trot after her, holding the eggs close to my chest.

“I’m not well,” she is telling the admitting nurse as I walk up and join her. Belinda leans her elbow on the beige counter and talks into the small portal open in the protective glass. The nurse scratches a plain fingernail against the side of her scalp. Her thin black hair is pulled back in a ponytail so tight I understand every contour of her particularly large skull. She taps a keyboard.

“Insurance card?”

Belinda fumbles her wallet from her purse. I am helpless beside her with my full hands, the sharp fluorescent hospital lights barreling pressure between my eyes. She conveys all of the relevant information and I try to memorize her date of birth, but it scrambles with her social security number.

“And what brings you here today?” The woman’s eyes stay on her screen, her fingers flapping over the keys.

“I don’t feel well,” Belinda says.

“Symptoms?”

“She’s vomiting eggs. Look.” I turn my hands and show the woman.

“You swallowed all those eggs?” The nurse looks from my arms to Belinda’s face.

“She didn’t swallow anything. They’re just coming out of her.”

“Do you have a fever?”

I bring the eggs closer to the window. “Here, we brought them for testing.”

The nurse holds up a hand. “Save them for the triage nurse. We’ll call your name when we’re ready for you.”

“This isn’t an average illness,” I point out. “I know it’s hard to believe, but—”

“Wait time varies. Have a seat.”

“This isn’t some prank.”

Belinda’s body bucks. The sound renews in her throat, a dry force pushing up through the sludge of dehydrated flesh, less horror movie now and more cat-with-a-hairball, but worse. Cat with a cactus in its throat. The receptionist is fast with a wax-lined paper bag. “In here, sweetie.”

The egg drops heavy in the bag. I look over my shoulder to see who in the waiting room might be witnessing this with us, but they all avert their gazes to the television hung in the corner or the phones in their hands. They probably think it is just plain vomit.

“They’re being produced inside her,” I inform the woman again.

Another egg comes, faster now, this one large and painful. Belinda clutches her throat. The polish on her index fingernail is chipped.

“She can’t sit in the waiting room like this,” I tell the woman. “Please, can you just—”

The woman is already out of her seat, flagging another nurse. She stands and picks up the phone and presses three numbers, waits for an answer. She puts her hand over the receiver and says to the second nurse, “Put on gloves and take those eggs from her.” I surrender the eggs to latex-lined hands. The double doors beside the admitting desk open. An orderly pushes a wheelchair through. “Belinda Smith?” She eases into the chair, her hair knotted in tufts and matted with sweat, grimacing with relief.

“Can I go with her?”

The admitting nurse isn’t paying attention to me. I lean into the window. There is someone else behind me now, a man in paint-splattered jeans with a dish towel wrapped around his hand, a circle of blood blooming to the surface. “Can I go with her?”

“No,” Belinda says. She holds up a hand. “I’ll call you.” The orderly sweeps her away.

The second nurse who took the eggs looks up at me. Her gloves are off. “Just have a seat. We’ll let you know.” She waves the bleeding man forward.

*

For our second date, we went bowling. When I picked her up at her squat yellow house on the north side of town, Belinda carried a dark green bag she said held her father’s severed head. “Just kidding. More like severed limb in general. It’s his bowling ball. He played four times a week until he died. I haven’t been inside a bowling alley since I was seven. Let’s see if I remember how to do it.”

Belinda looked like she knew what she was doing in her blue-and-white rented shoes and stretchy black dress, the tip of her tongue perched on top of her lip each time she approached the lane, but she rolled gutter balls. We were both terrible. We sat with our knees touching and drank cheap beer and talked about our families. I told her about my precise and distant mother who trained me in bed sheet hospital corners and a critical appreciation of literature. She told me about her distant and vaguely hostile brother. “He had kids young, by choice. I had them not at all. We envy each other in petty but meaningful ways.”

I rolled one strike. Belinda gave me a standing ovation.

Our first kiss in my car at the end of the night turned into two kisses, then three and four, until I stopped counting.

It was a very good second date.

*

The chairs in the waiting room are cold, molded beige plastic. There is no meaningful back support. I have to pee, but I’m afraid if I leave I’ll miss something. If Belinda died, would I be notified? If she was ferried away for secret government testing and surveillance, would anyone ever tell me?

I send a message. How’s it going back there? Need anything?

For the first time since our first date, Belinda doesn’t text back.

The nurse is laughing behind the partition. I can see her teeth as I approach, yellow and wet. She hides them when she sees me.

“Belinda Smith? Is there any update?”

“Are you another sister?”

“A sister? No, I brought her in. I’ve been sitting here the whole time.” I gesture to the waiting room behind me, where a round man in a windbreaker has taken my seat.

“One visitor at a time. Sorry.” The nurse drops her eyes to a computer monitor and I take a step back.

She never mentioned a sister.

*

At home my small apartment closes in around me. Here is all of the space I have to fill. It is not much. My entire home fits inside of a glance. There is the kitchen and, over a dividing wall, the living room that turns into the piece of carpeting closest to the kitchen tile that I call the dining room. Sitting at the table, the edge of the bed is visible in the other room.

The other women who have been here have tucked themselves in. Set their shoes by the door. Kept their purses close and folded their jackets as small as they could go, setting their personal items on edges, easy to grab for a fast getaway. On our third date, Belinda handed me her coat and purse to do with as I pleased. She kept her shoes on. She accepted a glass of Cabernet and walked with it around my whole apartment, studying the framed black-and-white cityscapes on the wall and bending to read the spines on my bookshelf row by row. “Oh, good, you shelve your Paley next to your Hempel. So do I.” She pulled a book down, thumbed the pages and stopped to read. I had not thought of my apartment as a dead thing until Belinda walked in.

I sit in one of the dining room chairs. The space quiets to the hum of the refrigerator. There is still the matter of the eggs on the table.

The next morning, I call in sick and stay home to check on the eggs to see if, in this strangeness, it is cold that makes them hatch instead of heat.

*

On Tuesday I call in sick again. Molly comes over. I remove the carton and place it on the kitchen table.

“These all came out of her?”

“Every single one.”

Molly grins and picks one up, holding it upright with her thumb and index finger on its top and bottom. Molly and I went on two dates three years ago. She is not my type. Too much patchouli and incense. Too many poems about the moon. But she keeps an open mind and a hopeful watch on the world, which is uplifting when I am not sneezing at the essential oils she rubs into her skin. It’s not just cats I’m allergic to, it’s everything. I am a difficult match, I know that. It is at the top of my profile.

Molly says the obvious. “Let’s crack this sucker open.”

I take the egg from her. “No. It doesn’t feel right. Not without her consent.”

“Has she returned any of your texts?”

“No.”

“Then she abandoned them. Strange that someone would abandon her own miracle eggs. But people are weird.” Molly shrugs. “Look at the bright side. At least you know this time, if you never hear from her again, it isn’t you.”

*

There’s always something. Maybe, at thirty-eight, I have used up all of my opportunities for love. Maybe I’ll plan another solo vacation this year. I still haven’t seen the Grand Canyon.

I just thought this time, with Belinda, it might be different.

When Molly’s gone, I turn off the lights, sit at the table with my computer and the dregs of the Malbec and search for Belinda. There is her photo and bio on the library’s website. She is Senior Reference Librarian, responsible for overseeing a staff of six and a budget. There is a Facebook profile set to private.

The eggs stare at me from the open container, one and a half dozen blank eyes waiting for me to do something. What does it do to raise their temperature and then lower it again? Can these eggs spoil? Do magic eggs rot? It would serve her right if I smashed them all. Would she feel it? I’ve heard stories of mothers startling awake out of bed when their children stop breathing in the night. Wherever Belinda is, does she feel me pick up this egg and toss it, gently, in the air? And in the air again?

I don’t know anything about her.

*

In class I have a hard time concentrating. I imagine the students cracking through enormous brown shells, fully formed as teenagers, slapping the classroom floor with bare feet, clucking out answers to the questions I toss at them like chicken feed. In the middle of a lecture about Hamlet I think of Belinda’s hair, the out-of-the-box red that shone in the restaurant lights and that turned copper as the first rays of sun came through my bedroom window.

Dust motes spin down, down, down to the bed when I open the door to my apartment at four-thirty every afternoon. She told me she wasn’t looking for a fling. “I avoided stability for years,” Belinda said with her head on my pillow. “I thought it would be boring. But boring is useful. I sleep better at night now. I want a girlfriend.”

The only way out is through.

I buy three dozen pasture-raised, soy-free chicken eggs and spend the weekend practicing egg recipes. If I’m going to crack open her magic eggs, I had better know what I’m doing first.

I make three different kinds of quiche, a soufflé that falls, eggs Florentine, eggs Benedict. I perfect a poached egg, a soft-boiled egg. I juggle three eggs successfully for twenty-three seconds before they land in neat splats on the kitchen floor. I check my phone and Belinda has not texted. There is still only her library profile when I search. I search again. Belinda + eggs + Texas. Four pages in I find a strip club in Amarillo, but it’s a different Belinda holding a glittering gold egg the size of her own head for the camera.

Deviled eggs, omelets, pickled. I wake in the middle of the night, exactly one week after Belinda slept here in my bed, and fry an egg as hard as I can to watch what happens, step by step, as an egg burns.

By Sunday evening, the kitchen is a chaos of crusted whisks, flour tracks, and unwashed silver bowls stacked in the sink and on the counter. You can’t expect life to return to normal after someone like Belinda. I don’t want it to.

In the end, I decide to keep it simple. Scrambled. Salt, pepper. Whole wheat toast.

But not yet. It’s almost midnight. I have no appetite.

*

Ten days after our third date I come home from work hungry and confront an empty fridge. Mostly empty.

I take one of Belinda’s eggs from the carton and hold it over the sink. It’s cold in my palm. The shell starts to sweat. I lick the moisture. Once, twice. I slide the whole egg into my mouth. It’s salty the way Belinda was salty. It hits my teeth. The tiniest tap.

I drop it back in my hand. There’s any number of ways I could do it. I could smash it on the floor. Crack it against the side of the silver basin. Crush it with the strength of my bare hand. Tap it lightly on the edge of a shallow bowl. Whisk its insides. Drip its contents into the sizzling center of the new frying pan I bought at Target on my lunch break.

I remove a plain white bowl from the cupboard. With my right hand, I tap Belinda’s egg against the bowl until I feel it crack.

My phone vibrates in my pocket. One-handed, I retrieve it and gasp. The egg drops in the bowl, final and flat. Belinda is calling.

“I lied,” she says. “This has happened to me before.” Belinda sighs. “No one ever wants to hear it.”

“Tell me.”

—

Julie Wernersbach’s fiction has appeared in Arcadia magazine, which nominated her short story “Happiness” for a Pushcart Prize, and is forthcoming in Bennington Review. She is the author of the nonfiction books Vegan Survival Guide to Austin (The History Press) and The Swimming Holes of Texas (University of Texas Press). Julie is the Literary Director of the Texas Book Festival and was an independent bookseller for ten years, at BookPeople in Austin, Texas and at Book Revue on Long Island. She currently lives in Austin and is working on a novel.