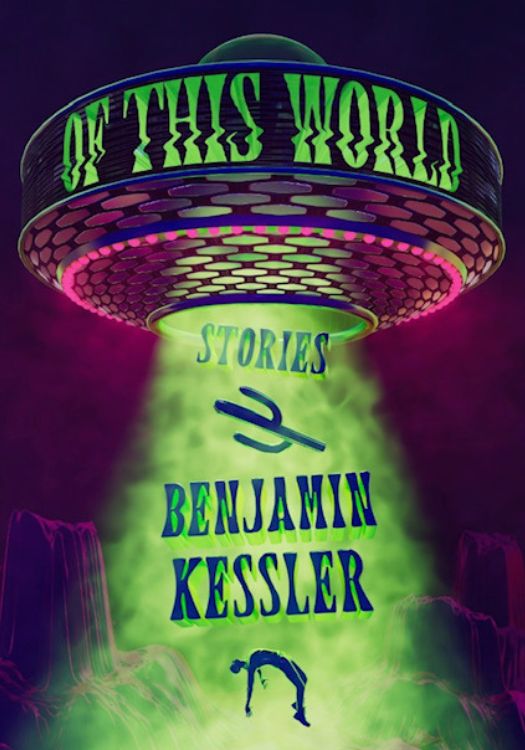

There is probably something distinctly strange about the era that we live in, and Benjamin Kessler knows this. In Of This World, Kessler’s new, debut collection of short stories, reality (as we have come to know it) plays out with the specter of fantasy trailing closely behind.

Characters come and go, but one thing remains the same throughout: they live in a version of our world where reality stretches and bends to take a shape that is more than realistic. Sometimes hyper-realistic, sometimes leaning on outright fantasy, the tones of these stories shift between different types of odd and speculative.

The book is sometimes horrifying, and pulls no punches in hitting close to home, though steers clear of obtuse injections of politics. Other times, the stories are jovial, and provide a sense of respite that is welcome in the largely foreboding drama of these stories. This results in something particularly knowable to the average post-quarantine reader, who might be used to experiencing apocalyptic happenings that coincide with the mundane droll of middle-American life.

This is a motif that is present throughout the book, with characters often having to balance life-changing crises with typical interpersonal conflicts, though the settings and circumstances whip around wildly throughout the book. The more absurd the scene becomes, the more familiar the tensions between characters are.

Once the book goes post-apocalyptic, it also starts to follow a married couple being worn down by repetitive arguments. At the same time, regular problems, like running an interesting blog, are taken to fabulous extremes with characters caught up in a preoccupation with insecurity. In this way, the stories grow relatable as they also stretch into quite dramatic scenes, which is an aspect of this book that I quite enjoyed.

All of the stories in this book can be taken to be more or less contemporary to the last five years or so, though some are framed as being mostly classic stories with tensions and images that have existed for decades, whereas others refer to rather specific moments in relatively recent history. In several places in this book, familiar images form distinct moments in history and culture, with callbacks to headlines, phases of quarantine, and now-common sources of both drama and joy.

After reading the collection, one of the stories that has stuck with me the most as being both delightfully surprising and perfectly of-its-time is “Alert”, which appears in the latter half of the collection. If the setting of recent-day Hawaii with the image of a missile alert coming in on one’s cell phone means something to you, then you probably already know some of the events of this story. But the Romantic-esque telling of the event, focused on the feelings and meditations of a particular character, who is consumed by overlapping crises in both personal and public life, is what makes Kessler’s telling unique and charming.

Pulling on and calling forth the strangeness of everyday experiences, as we have recently come to understand them, provides a lot of the strongest imagery and most relatable content in these stories. You might feel like you already know some of the situations and predicaments that the characters find themselves in throughout the various plotlines, but Kessler’s unique style of overlapping tensions as well as his distinct command of point-of-view and voice, create something new, if not relatable. Through this, he allows his audience to participate in early nostalgia while also connecting to a sense of worldliness that draws people together during times of crises. After all, we are all in this together, are we not?

In that vein, even the more timeless stories have overlapping themes carry themselves clearly into present-day contexts. One of the earliest stories “Hall of Meat” follows teenage skateboarders with priorities that are all over the place. A silly sort of sadness comes out of it, that fits in well with the heightened drama of many of the other pieces. The quest for good skate footage with the impending end of high school hanging overhead creates an emotional landscape where readers, whether they skate or not, can feel something for at least one of the characters, if not all of the characters, and perhaps even, themselves.

Though the stories are consistently rather timely and largely bizarre in affect and content, they vary quite notably in form and genre. One story, “I Ate Batteries for a Month and Here’s What Happened”, is a fairly one-to-one embodiment of satire, that (I hope to God) rests on a fictional reimaging of a common social media character who takes drastic measures to stand out from the rest. Some might find this poignant while others could think it prudish, but by the end of the story the image the reader is left with is, in my opinion, frightening, hilarious, and out-of-pocket enough to be considered buzz-worthy. It is the kind of story I could forward to my grandmother for a laugh, or try to pass off to my tween niece as a cautionary tale about the world she is growing up in.

Satire ends up being a driving force for multiple stories in this book. It is a pseudo-gothic sense of collapsing dichotomy that allows some of these situations to take up meaning in Kessler’s work. Through the narration of these stories, he presents himself as a post-quarantine beatnik, experimenting with the formalistic aspects of prose while sharing a preoccupation with Americana in the modern sense that puts a tedious, insightful spin on the absurdity of everyday life. I advise readers to not expect too much face-value, rather, the exigence of this work comes from the supposition and playfulness of it all. Do not get stuck figuring out what is going on when Kessler diverges into farcical advertising copy or emotionally meaningful instructions for building a box, instead, stick with the stories for the humor that comes out of juxtapositions, and the sense of belonging that is possible if you, too, feel disquieted by the events of the last half-decade or so.

There are strange things around us all the time, some more palpably odd than others. What Kessler does here that feels ultimately very successful to me involves layering the ordinary with the extraordinary to create stories that are both fantastic and accessible. Moments of recent history that you may have glossed over will come back to surprise you in this book, and even if you have been living under a rock (or perhaps in a tortoise’s shell) you will find characters that are lovable, detestable, and everything in between.

Kessler, Benjamin. Of This World. Game Over Books, April 2023. 156 pages, $20.