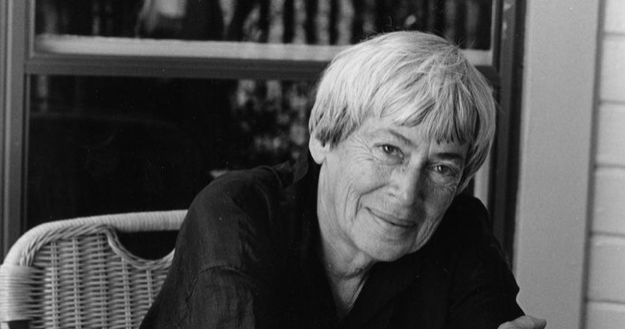

It has now been two weeks since the death of Ursula K. Le Guin, and Portland Review is coming to terms with the loss of one of the most beloved and impactful members of our community. Thank you, Ursula K. Le Guin, for teaching us, inspiring us, and sharing with us your stories.

Ursula K. Le Guin first taught at Portland State University in 1979, alongside Professor Tony Wolk, in a science fiction writing class—likely one of the first such writing courses in the country.

“The first evening our group met, Ursula wasn’t very happy with the classroom she and Tony had been assigned,” Molly Gloss, who was a student in the 1981 workshop, remembers. “It was a typical smallish room with rows of student desks facing a teacher’s desk and a chalkboard wall. There were twenty of us, twenty-two counting the two of them. She wanted us to sit in a circle so we could all see each other as we talked about our work, but the room wasn’t large enough to accommodate that sort of rearrangement.

“One of our group worked on campus in an office in Cramer Hall, and suggested we could move our meeting there—she thought there might be room for all of us to sit in a circle on the carpeted floor. The student had a key to the office, and she took Ursula around for a look. Yes! So we trooped over to Cramer and the move was made, though, as far as I know, it was never officially approved—we were a bunch of anarchists!—which, for Ursula, surely was part of the appeal.”

Being in a classroom with Le Guin was not unlike reading her fiction, which occupies a space that’s never quite what we expect, setting us beside those different from us and forcing us to come face-to-face with one another and listen.

Writers of speculative fiction like Le Guin are often called prophetic, but Le Guin surpassed this definition. Her stories don’t just show us future worlds, but worlds in which we all can live: the inhabitants of Earthsea are brown-skinned, the beings that inhabit the world in The Left Hand of Darkness are able to shift genders. These are stories that have the capability to inform, to illuminate, to include, to heal, and they seem so timely, so immediate in many ways, but they have been in print for nearly half a century.

In her lifetime, Le Guin penned hundred of short stories, over twenty novels, a dozen books of poetry, seven essay collections, thirteen children’s books, five volumes of translation, a craft guide for fiction writers, and even the libretto for an opera. When a student once asked Le Guin what she does about writer’s block, she replied in her low, harp-string voice, “I go to the well. I keep going to the well, and it fills.”

Le Guin’s writing has created a swift undercurrent beneath literature that writers today so frequently dive to and pull to the surface, and her influence can be seen across genres and generations of writers. Though she was often referred to as a science fiction writer, Le Guin refused this definition. (“Don’t shove me into your damn pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over,” she said in a 2013 interview with The Paris Review. “My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions.”) And it’s true—to confine a writer like Le Guin to a single genre seems both irresponsible and inconceivable.

As Portlanders, we were fortunate enough share a home with Le Guin: magic, tentacles, and all. Since her time as PSU faculty, Le Guin contributed both her writing and and interview to Portland Review, and her work has been taught and referenced on campus consistently. Professor Katya Amato teaches the Earthsea series in her upper-level English class, in which a student once sang for Le Guin “Where my Love is Going,” a boat song from the Earthsea story “Darkrose and Diamond” (Le Guin loved it, and struck up a correspondence on the spot), and Professor Gabriel Urza will teach a graduate seminar on her work in the spring. When Professor Wolk thinks back to first meeting Le Guin in Portland—warm, prickly, brilliant, fiercely funny—he says, “it was like striking gold.” It’s difficult to imagine our city without its resident goddess, her watchful eye no longer looking out from the house in Forest Park.

Le Guin was rarely ever not writing, though her relationship to writing fiction changed as she neared the end of her life. Her last published book was a collection of short essays, entitled No Time to Spare, and is made up of a series of blog posts Le Guin composed almost daily on the things, large and small, that mattered to her. These small pieces have the same gentle gravity as her other works, as though her resonant voice and sharp, compassionate gaze are always there behind the pages, leading us to what before we could not see. Even until she passed away, Le Guin was writing.

“I have been letting a story lead me where it will,” she wrote in an email to Professor Wolk, one week before her death. “Very slowly. It is such a pleasure to follow, to find out where it’s going. Like walking beside our creek in the California hills. Of course the creeks there mostly stop running in the summer. But they’re there; if you dig into the sandy adobe it gets damper and damper. And now and then the water runs out in the open again for a little ways.”

Thank you to Professor Katya Amato, Professor Tony Wolk, and alumnus Molly Gloss for sharing their memories with us.

—

Rayna Jensen is an MFA candidate at Portland State University, where she teaches writing and serves as the co-editor-in-chief of Portland Review.