Shit Cassandra Saw by Gwen E. Kirby is a collection of stories about women: the women relegated to single lines in our history books and the women who are never written about at all; women on the verge of breaking down, who broke down long ago, and who have only just begun. There are the occasional men who orbit their lives, with whom they fight, hurt, cry, and kiss, but only two of these 21 stories are told from the perspective of a man. Men are incidental, until, of course, they are not.

The day I began reading Shit Cassandra Saw, I happened to go on a particularly awkward Tinder date that ended with a particularly slobbery kiss. The next day, he asked to see me again, and I sent off a polite “this isn’t what I’m looking for right now” text. When I checked my phone an hour later, he had left a two-minute-long voicemail demanding further explanation. The next day, he sent a barrage of texts, and finally, a photo of his bare torso that was inches away from revealing his nude bottom half.

At first, I laughed—even felt a little sympathy for this person’s misguided attempt at a connection. But as the texts kept coming, his messages pointed, veering towards aggressive, I thought, “Shit. He has my address.” Sure, most likely I would never see this person again. Most likely, it would be a funny story about a guy I went on one date with who simply could not understand that a woman was not interested in him, because don’t you know he makes a lot of money and has a very big loft and I mean would you look at this photo of his abs?

But the worst-case scenario—the one where the guy from the random Tinder date does show up at your door—is what women have been primed for. It is in every directive not to walk at home alone at night and every sexual assault plot thrown casually into our favorite TV shows in a lazy attempt at character development.

So, when I read A Few Normal Things That Happen A Lot, the second story in Kirby’s collection, which opens with a woman who is told to smile but has recently grown fangs, and in retribution she bites off the man’s finger then gets indigestion from accidentally swallowing his wedding ring, I laughed, I smiled, and I thought, “Nice.”

It is all very funny until it is not and then it is funny again. Kirby understands this, and in these stories of the brave, the beautiful, and the damned, she lets it rip.

The collection begins with its eponymous story: Cassandra, the Trojan priestess, is cursed by Apollo with the gift of prophecy—only to never be believed. In Kirby’s version, Cassandra is no longer a silent victim of the men who will not listen; she laughs at their hubris and takes pleasure in all she will not tell them, including the satisfying fact that in the future, “Trojan will not be synonymous with bravery or failure, betrayal or endurance,” but with condoms.

Cassandra is the first in a series of stories that dot the book: the stories of women from history whose most noted traits have typically been the traumatic ways their lives ended. Kirby reimagines their narratives, demanding more. What if Cassandra laughed at the Trojans, and Boudicca the warrior queen played baseball? What if the witch hanged at the stake secretly gave abusive husbands tinctures filled with urine before her death?

The collection does not live in historical what-ifs alone; Kirby takes us from ancient Greece, to dystopian futures, and then right back to the present day—a teenage girl seeking out her first kiss or a woman trying to get pregnant while arguing with her spouse about what to eat for dinner.

Kirby’s writing is fearless, refusing to be confined to one form. One brilliant story takes the shape of a disgruntled Yelp review gone off the rails while another centers around a cheating mother who encounters the ghost of a judgmental evangelical preacher. In a moment of meta-fiction, she takes a stab at the lifeless literary character she calls “Midwestern Girl”—the girl who appears just in time to revitalize the main (male) character’s life before she disappears again. Kirby skewers the authors who utilize this trope and gives the “Midwestern Girl” a sense of agency; for once, the leading lady in her own story.

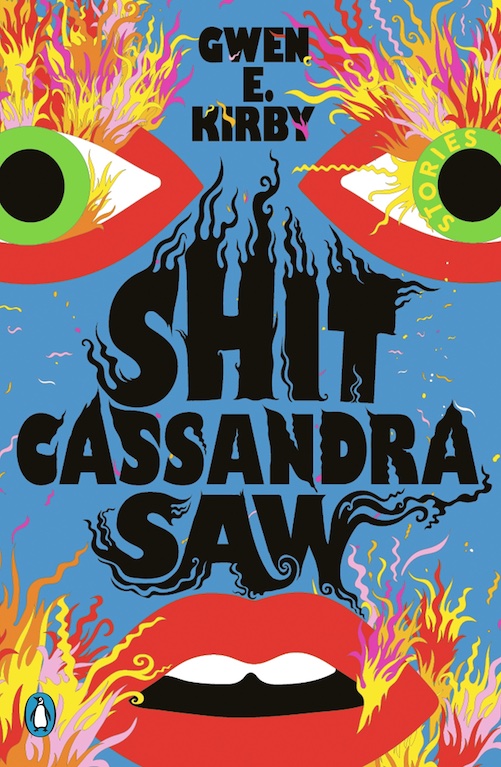

Kirby’s wit is acerbic and her rage palpable. Even the cover of the book implies fury: flames shooting out of two huge green eyes, burning onto each corner. And why wouldn’t she be angry? Most of us are, and Kirby’s free-wheeling rage is cathartic to inhabit, if only for 288 pages.

But it is not only her fury that makes these stories so enticing. Many of my favorite moments came from the scenes of tender intimacy in female relationships. In one story, a woman walks into her friend’s bedroom to find her lying naked on the floor. She pours a bottle of wine into two bowls (the only cups available), strips off her clothes, and lies next to her in silence. In another, three teenage girls work at the second-best unclaimed baggage store in Alabama (yes there are two, and yes, one is better). They sell what others have forgotten and keep the items that are never chosen. One day, they discover a bright white stuffed animal and become enamored. They are on the cusp, stuck between girls and women, fighting over boys, fighting to fit in, and fighting to find something (anything) to give their lives meaning. Yet here they are, with all of their teenage angst, sitting together, using a brush to comb the hair of a large stuffed animal.

None of the women in these stories are perfect. How could they be? They are competitive and jealous and mean; they cheat, lie, and self-destruct. But they are not frozen—quartered to the annals of traumatic histories and literary tropes and static two-sentence plot points. They are in motion: trying and failing and trying again to make sense of their lives and the people within them—to write a story that is their own.

I do not want to give too much away; much of the joy of reading Kirby’s work comes in the boldness with which she turns the reader around and sends them off into the dark. It is a book of surprises, with flashes of recognition that make your palms sweat and moments where you find yourself feeling unexpected fondness for evangelical preachers and late-night Yelp reviewers. It is a book for all of us to read, but one that only Kirby could write. A book that is thrillingly unique and triumphantly her own.