The nurse left work at five o’clock, or later. For night shifts, she left at five a.m., the sun cusped in the mountains on the edge of town. The work never left the nurse, the nurse’s husband always said when he was alive. When she held his hand, she had felt for a pulse.

The nurse’s husband used to leave for work at six-thirty. He typed all morning and filed all afternoon: contracts. I, the undersigned, waive any. We, the company of Finch and Patrick, hereby. When he left work, he was gone. When he left her, he was not.

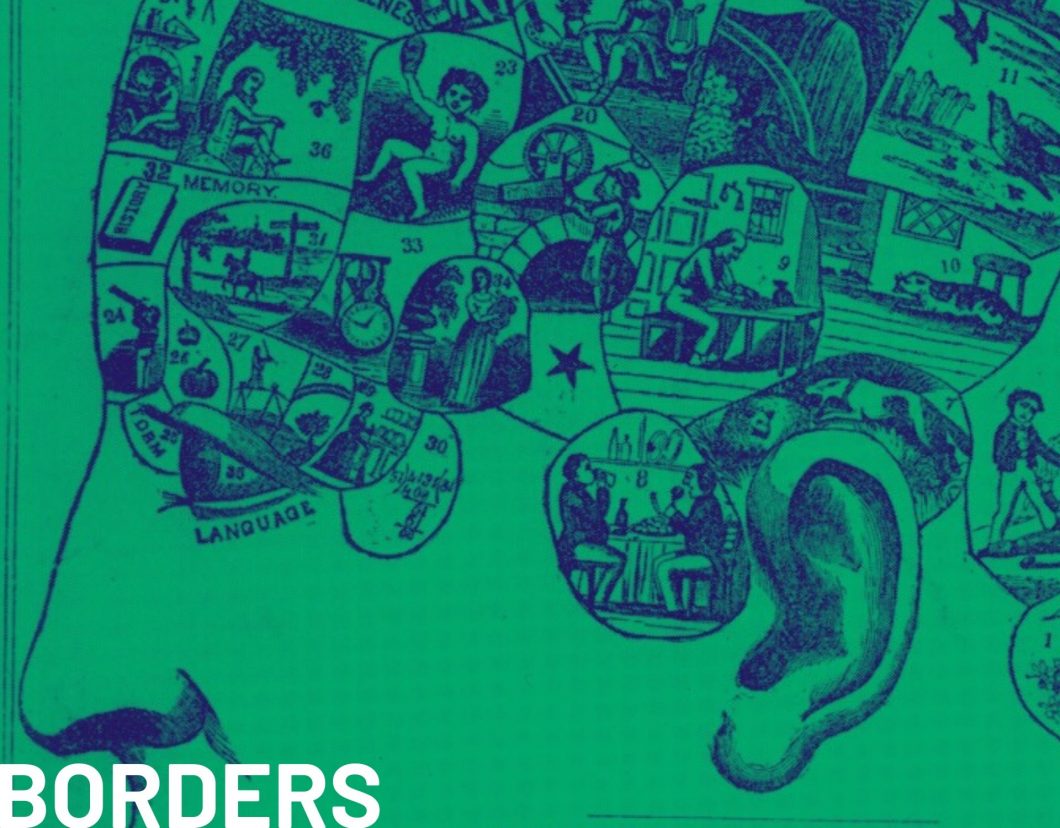

The nurse’s husband used to read over his lunch hour, profane books about lost sciences. If he had found it ironic to read about alchemy on an e-reader, it only heightened the pleasure. He dabbled in phrenology. At parties, he had been popular with other men’s wives. He felt their heads and they had laughed; it wasn’t sexual. He had been gaunt and gawky, a learned flamingo. In self-analysis, he felt his skull and found he had great memory and a strong sense of colors. And vanity.

The nurse never believed in his inexact sciences and pushed his hands away when he had tried, saying, “No, no party games tonight.” In their dating years, she only used tester bottles of perfume. She clipped coupons for dental floss, had left them out for him. She had feared for his gum health and hoped that meant she had really loved him.

Before he died, the nurse’s husband once read her phrenology while she slept. He woke up from a dream and she was on his shoulder. He brought a hand to her scalp. She had a sense of the connectedness between numbers; she had a memory of people. She moved in her sleep, but he kept touching. “You yearn for routine.”

She had murmured, “Don’t,” but he kept on. She had a beautiful skull, scalloped ridges near the neck and smooth roundness above.

Her alarm went off. “Damn,” she had said, rolling over and off the side of the bed. She slipped her nightgown over her head.

“Stay,” he had said.

“You’re always asleep. When I see you I don’t see you.”

“You’re beautiful.” He had reached for her naked torso. “You have a beautiful head.”

“Good night,” she had said.

Sitting at a stop light, a day before he left her forever, a day distant from a changed life, she felt her own head, wishing the lines and bumps were map lines, roads and rivers already knowable and known.

The sun rising over the crest of a hill.

Ten hours before.

Saline drips. Computer keys. Coffee cups.

Two hours.

At the end of the day, she drove home, then passed it. Kept driving. Wanted to prove she could exist on an unfamiliar street. Parked her car and waited for him to notice and reach out for her pulse. Waited for a phone call.

If she had come home, would she have found him in time?

Her skull said maybe.

Her head said yes.

Her heart said thump. Beat against her ribs, a child in a locked room.

Thump thump. Perhaps for the first time, she felt her own heartbeat.

Image: Phrenology Journal (1848), Public Domain.