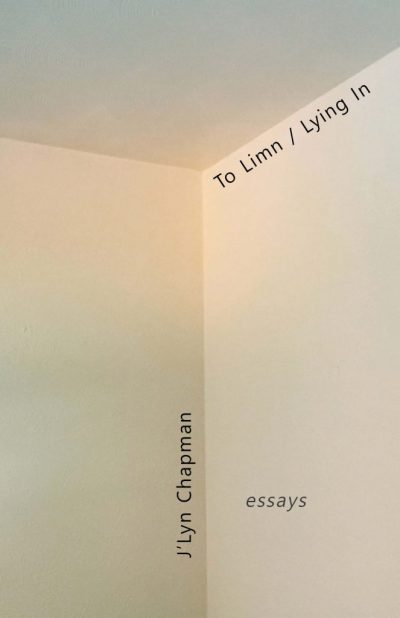

Theoretical physicist Richard Feynman once said about sight: “The brain has developed a way to look out upon the world. The eye is a piece of the brain that is touching light, so to speak, on the outside.” J’lyn Chapman’s newest book To Limn/Lying In reminds readers to look out upon the world, as well as inward—to touch the light that lives outside of ourselves. This collection of meditative, lyric essays is grounded in the tender exploration of how light enters and moves alongside the author and her family in their Colorado home.

Inspired by Uta Barth’s photographs and Francis Ponge’s notebooks during the German occupation of France, Chapman traces the light in her home and all it touches, from the silhouettes of her young children to the shadow-shapes brought by dawn. She communicates with/through light, interpreting its waves and subtle, unperceived rhythms. Translating light and its absence, she focuses on the periphery—the moments that pass without particular attention.

The phrase “lying in” was once considered the period of time a mother was home-bound after giving birth, a time of rest and isolation from the outside world. And, with isolation comes the mind’s murmurations. Chapman writes “I enter my thoughts at my own risk,” and she embraces this vulnerability, following her thoughts where, and when, they lead her. She says that light, like her mind, is capacious and “must open itself to the world.” As Chapman moves from room to room, from garden to porch, her mind unfurls and quivers “as a thread pulled tight,” a thread she keeps strumming.

She nurses light and language as she nurses her children, folding each moment as a letter to the world of which they are now a part. She writes, “Now that you are here, under this firmament, through no choice of your own, you should know the life I gave you is unsustainable.” There’s a durational temporality exposed by light and darkness, and grief becomes wonder, and vice versa. Every day is a discovery, an emergenc(e)(y). We are ephemeral—a brush of the hand, a distant contrail—and every day is a reminder of our impermanence.

Chapman’s words splinter and leak their own incandescence, pulling us toward a warm, glowing center. We move alongside the author in her sleepless, milk-stale house as stringed pearls of light scatter along the walls. Time blurs and bends as Chapman and her family shift their shapes inside the walls of their home. It’s as if the author’s own body metamorphoses into a chrysalis she can’t unspool: “My body the site of return, duration, intractable otherness.” She becomes a vessel her children rely upon to survive and a sanctuary they seek for comfort and closeness. “Now the child puts her mouth on mine,” she writes, “and I call it a kiss, so desirous for togetherness to rise from breast to lips. Until it lifts and wings away. The mother is made for the child’s mouth, but the child’s mouth is made for the world.” An ineffable longing lingers as Chapman observes her children and how they relate to the world with curiosity and openness. Parenthood, like light, wounds and pleases.

Honest in her restlessness and desire, Chapman embraces her vulnerability as she grapples with delight, exhaustion, and depression: “I keep wondering how it’s possible to feel this way, how it is possible to make humans inside my body and to be so sad. How to love so absolutely. . . and how to despise the day, to hate waking.” In this way, Chapman reveals her living wound. Sorrow, grief, joy, and wonder exist simultaneously. Mother is beyond noun and verb; mother is expansive and multiple. Mother is always becoming.

To Limn / Lying In by J’lyn Chapman is a study in stillness and movement, in avowal and reservation. She writes, “To produce a space of darkness is to be bathed in light.” The absence of one thing can bring the emergence of another, and we often long to bask in the glow of what we know will fade. Grief is inseparable from love. Within each of our lives, there exists multiple exposures, a layering of vestiges. Our lives are entangled with those around us, and each trace is auroral, reaching out into the soft darkness of the unknown. Our relationships are how we survive the terror of the world. It’s here, in the uncertain now, we find ourselves at the edge of the decipherable. It’s here where we look out upon the world and reach for light, longing to be flooded by it.