Under the bad neon hardware store lighting in brunch and boutique Ranelagh I flap a six-tint color swatch at my med school classmate. As if a ticket on a commuter train, nudging to get hole-punched by the conductor’s signature stencil, irregular slashes like a hasty wolf attack. “Liquid skin: cannot be unseen,” Molly warns me off slathering my bedroom in peach paint. Her ex-roommate did acid once and morphed into their bisque-colored kitchen wall, stuck for hours, a formless blob of silly putty.

I picture skin drizzling out of a dented paint can, foam roller spreading it across a rippling tin tray, elbow motion like the squeegee men of my 1990s childhood in NYC—who threw soapsuds at pristine windshields, and raked bubbles across our quivering faces at exits from tunnels and traffic slowdowns, honks of horns, and our inability to maneuver around a jigsaw puzzle of gridlock. I hear the blisters popping as the skin thins sparse and tacky. Tender as a raw sunburn, weeping herpes, sandal-chaffed heels. I envision myself as Zach Braff in Garden State, receding into that ugly couch-patterned wallpaper, shirt cut from the same cloth–a modern take on camo. Only I’m glued to a wall by a sweaty fabric Band-Aid. Edges curling like paint peeling, skin sloughing, congealed layers pried apart.

I abandon peach, from Soft Coral to Apricot Crush. Spend three months hammocked in banana cream pudding. My bedroom is Banana Dream #6, the most dilute tint of yellow on Dulux’s comfort food palette. As I lay on my back, woozy from a strawberry tab of sleepy-time mirtazapine that disintegrated fizzy on the tip of my tongue, my pillow sponges into a forgiving vanilla wafer, my bedspread entangling like a rhythmic gymnastics ribbon of salted caramel. Leaden head and dead-weight body levitating on a Care Bear cloud of primo pharmaceuticals, supported by the zero gravity of goo.

Around my defunct fireplace, I foam roller, then precision brush, a wall in Wellness. A tint of mint meant to be paired with Willow Tree and Enchanted Eden. To cultivate an aspirational landscape for those too wiped out for Headspace. An app that urges its users to be mindful, when all I want to do is lose my mind. An electronic adjunct to, or substitute for, SSRIs, the class of drugs that throttles my orgasms, forcing me to bludgeon them out of my cervix in my nacho shaped, economy shower stall. I place two cinnamon-scented candles atop the matte black mantle. Inhale the artificial hominess of wax imitating baked goods, sleek red stalks complementing the gentle green of my would-be garden.

***

When I get home from being a shadow at a prestigious hospital, the twice-per-decade Irish census is masking taped to the stained-glass door of the single-story rowhouse I’m renting in Stoneybatter. An “up-and-coming” neighborhood in Dublin 7, where Wi-Fi network names are random strings of characters and meat pies are served with chillwave music. My only insights into the presumed neighbors I’ve never seen are copies of Patti Smith’s Just Kids and anthologies of Kierkegaard left on Ikea side tables. The census is a peaceful Zoloft green, stapled down the middle so it fans out like a centerfold. In the spirit of depression, or anti-depression or whatever, I open it up on my bed. There are rows of smiling teeth where you can fill in the blanks. I blue ink the block letters for “AMERICAN” and “JEWISH.” Might as well scrawl “ABERRATION.” Islam is a checkbox you can tick. Protestant, the most abhorrent of possibilities, is missing conspicuously among other denominations of Christianity: the Troubles stowed away in history books.

The booklet matches my tropical duvet cover’s seafoam green background and a collection of Mira Gonzalez’ poetry called i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together, itself matching the banana pudding bliss of my bedroom. I snap photos of the scene illuminated by my “skylight,” which doubles as a playing field for bird shit target practice. My only portal to the outside world, this awkwardly angled ceiling-window looks as though it were designed to extend into a chimney. It’sr embedded in a cold tin roof, upon which restless cats tap dance and puffed-up pigeons coo. Its fine finish of soot, indistinguishable from sky, filters the scarce sun when it deigns to sojourn in Dublin. My life is overshadowed by shit and shade.

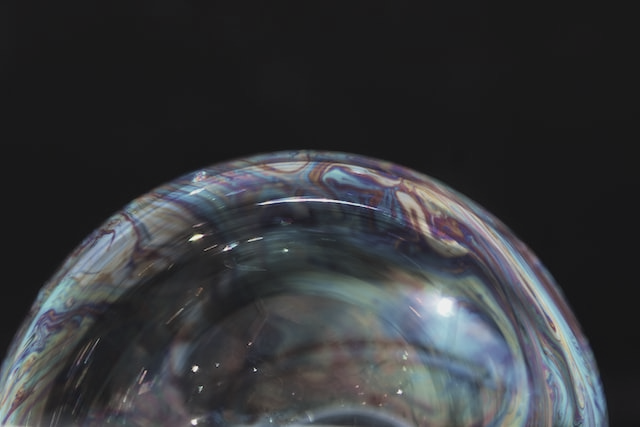

I call my photographic composition “sad girl still-life,” to commemorate the emotional tenor of the city where I’ll be captive for three more years, while I slog through medical school. Butt attached to my self-assigned seat in the lecture hall during business hours; body sunken into my mattress topper on nights, bank holidays, and weekends. Every day in Dublin, damp and despondent, weather-worn asphalt slicked in prismatic oil pollution passes for a mythical urban rainbow. Once, I laughed out loud when a belligerent passerby yelled, at no one in particular, “Ye feckin’ miseryhole.” He elapsed into the shroud of fog, from where I had emerged, too swiftly for me to rally in solidarity, “You and me both.”

By the end of the week, I masking tape my completed census back on my door where I found it, eye level and shackled beneath the bronze knocker. Someone will pick it up, saving me a trip to the Post, housed in a shopping centre among stores with vaguely offensive names. There’s the Chinese takeaway “Chess,” evoking the model minority stereotype. The bakery “Thunders,” recalling the fate of your thighs according to your grandma’s adage: Once on the lips, forever on the hips. And the Catholic secondhand store “Respect Charity Shop,” which sounds straight out of a feminist satire—only chaste women in potato sacks deserving of respect, everyone else a charity case. A shadow at the hospital, I already feel like I’m donning a potato sack out of deference. Our school’s insignia-embroidered white coats do not come in women’s sizes. Stiff and boxy, my coat starches my shoulders in place, its sleeves surpassing my fingertips. My hips sway past its boundaries, requiring three buttons ajar to accommodate. I feel like a child teetering on her mother’s high heels—only, trying on masculinity for size.

***

Four years later, the pandemic will strangle the globe. By then, I’ve long since dropped out of med school in Dublin, and moved back to The Polychromatic States of America. On Tinder in Philadelphia, I meet a boyish man whose ruddy body glints under the glow of my bedside lamp, as though a gentle kiss of dandelion dust has dotted his wisps of eyelashes and clung to the brush of his evenly trimmed chest hair. For the first four months, our coupling subsists solely within the vacuum of my living quarters, he entirely out of context. One crisp fall day dwindling, we venture out on a field trip to a stately 19th-century cemetery—bounded by swerving Woodland Avenue—where string lights dangle from the beams of a dismantled wooden structure, tags on trees correspond to an arboreal field guide, and groundhogs burrow under shallow headstones, a subway system of tunnels undercutting the soil we stand on. The main gate clasps hands from twilight to daylight: we’re circumspect about getting locked in, having to hop a fence, ripping our pants. And this is how I discover he’s unfamiliar with Corduroy, the famous storybook bear. How he had explored the department store after hours, in search of the button that was missing from his eponymous overalls, the night watchman finding him in a display bed and returning him to his shelf among uncurious toys. How at the laundromat, he’d slid off his chair to go on another quest, and when his friend Lisa and her mom couldn’t find him close to closing time, they had to leave him behind.“I only read novels,” the boy of dandelion dust gloats with some sense of irony.

Before we began fucking, I had inquired, regrettably, as to whether he had any tattoos. He said no, but once, after a few Four Lokos, considered having the last line of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest sewn into his pink skin. The idea was painfully unoriginal, he knows now, but would be happy to defend the merits of the book, with its gratuitous jargon and nested endnotes. Like all liberal arts college clichés, he venerates the canon of the Great White Man Author, is unduly impressed by the girth of a heap of papers, only those with the acuity and stamina to decipher esoteric works worthy of their grandeur. Nevermind the valuation of well-connected white men is carried out by other well-connected white men, a daisy chain of dick sucking. “Spare me your dissertation,” I said.

Another night, we joked about common red flags in men’s dating profiles: “writers” unable to hammer out a coherent paragraph, “feminists” unable to name a female author whose work they admire, those who haven’t read anything new since high school, those whose favorite books are unmistakably misogynistic. “Please don’t tell me you have two copies of The Corrections,” I egged him on with a book in line with his strain of hipster snobbery. Years earlier, scavenging for spare books to build a library in the psych ward of a teaching hospital, the ubiquity of Jonathan Franzen among my “progressive” neighbors had been second only to the omnipresence of Angels in America—that surplus attributable to queers moving in with other queers, making copies redundant. I’d acquired a sturdy stack of paperback bricks.

“Have you even read The Corrections?” the boy of dandelion dust asked, annoyed. Like when parents say you at least have to try your repulsive peas before pushing them over to the other side of your plate. Like when a cishet man asks a woman how she knows she’s gay if she’s never tasted dick. No matter that from a young age, we’re taught to internalize whose experiences to accept as universal, whose to pigeonhole as niche; who’s responsible for partaking in others’ perspectives, who needn’t do the research. Why poison myself with the musings of the arrogant and overrepresented? Why hold more space for what I’d like to carve out of me?

“No,” I said. “I’ve already read enough excerpts and takedowns by people whose opinions I trust. Like, why would I read a book by a man who’s never touched or so much as talked to a woman? He has no clue how to write a sex scene and doesn’t care to learn.”

“Maybe he isn’t having the kind of sex you’re having,” he retorted. “Or want to have.”

I wondered whether the kind of sex I allegedly wanted to have was the kind of sex he wanted to have with me. Or whether he was over-assuming, bloated with crushing hope.

***

It’s the week of the Twitter meme: “Don’t fuck men who read [insert: DFW, Bukowski, Palahniuk, Ayn Rand, etc.], or just don’t fuck men, period.” A callback and counterpoint to John Waters’ fervent wisdom: “If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ‘em!” I send the boy of dandelion dust a screenshot of poet and Twitter personality Mira Gonzalez smoking weed out of Infinite Jest, glass stem projecting from its hollowed-out pages. It looks like an object a kid would’ve hidden candy in at sleepaway camp, after their counselors got smart to the tampon boxes and slashed tennis balls passed from bed to bed. Mira’s midnight blue lighter matches the ombré sky on the cover. I muse over how Bic became the company synonymous with newsstand cigarette lighters, mechanical pencils, and the cheap disposable razors teenagers snag their legs on, by accident or on purpose, slices of skin serrating like old-fashioned pencil shavings.

Months later, the boy will invite me to his place for the first time. Ahead of returning there, I’ll submit a disability accommodation request: my digestive organs, surgically altered and my body short in stature, his ADA-compliant toilet is too high for me to use comfortably and effectively. A step stool would suffice; the Yellow Pages would align with his analog aesthetic. Really, anything to prop my feet up, boost my knees relative to my hips. “Would a regular big book work?” he’ll text back. Summoning an image of The Holy Bible, pilfered from the bedside drawer in a dingy motel room, cordoned off from the parking lot by smoke-infused drapery. “Something the size of, say, Infinite Jest 😉 ?”

“Hahaha, that would be perfect,” I’ll reply.

In anticipation of my arrival, a medley of rejected books will be stacked up, dutifully, against his bathroom wall: an anthology of poems, Booker Prize shortlisted Ducks, Newburyport. Having been stuck with Lucy Ellmann’s “insufferable narrator” for six-hundred pages, the boy of dandelion dust will have finally given up when she’d admitted defeat in feigning interest in the aurora borealis—its clashing green and purple color combo, its spooky sounds.

“Fully support the use of Infinite Jest as a bong,” he reacts to the Twitter post, amused by Mira’s resourcefulness in defiling his beloved, though not quite grasping what defines a bong, the part about the water. “I think I’ve read one of her books before,” he adds.

“Her poetry book?” I clarify.

“Yaaa.”

“The seafoam and yellow one?” I double-triple check, pleased to establish that we may, in fact, have a single book in common, our cultural references intersecting despite me being raised by Sesame Street, he by classical music and cinema.

“I was remembering pink,” he says. “But that’s the one.”

His description of the cover confounds me.

i will never be beautiful enough had matched with Banana Dream #6, was an integral part of my sad girl landscape. A banana is not pink, unless it is Andy Warhol’s, unpeeled, on the sleeve of that famous Velvet Underground & Nico record. Curious, I fish the spine of the book out from my bookshelf, place it on my summer sheets, text him a photo of my mop-head pup availing of it as a pillow, and curse him for soiling my memories. Like that time I’d gotten off to the image of a guy’s crooked dick for an entire school year; then, the following summer when we were reunited, found it curved in the opposite direction from how I’d been remembering it. “Lolll, Katie, it’s literally 40% pink,” the boy of dandelion dust argues. Is it possible the book is actually seafoam green and peach, neither of us correct nor incorrect, exactly?

The next morning, I slide my bedroom curtain open. Align Mira’s book with my forearm. In another city, another country, where my portal to the outside world isn’t a would-be chimney shrouded in soot, and speckled in pigeon shit. The unfettered East Coast sun is more accurate than bad neon hardware store lighting; a celestial bounty that might birth a banana, or at least some sort of vegetation. Unlike clammy and impotent Ireland, where all the fruit with red insides was imported from Belgium or Portugal. I think back to the peach paint, liquid skin, tacky blisters, the paralyzing prospect of fading flush with a background. Under the glow of warmth and clarity, and the kinship of he whose pink skin has been melding with mine, I inspect my arm. The book does not bleed into it; I do not become the book.

***

Image: Photo by giovanni cordioli, via Unsplash.