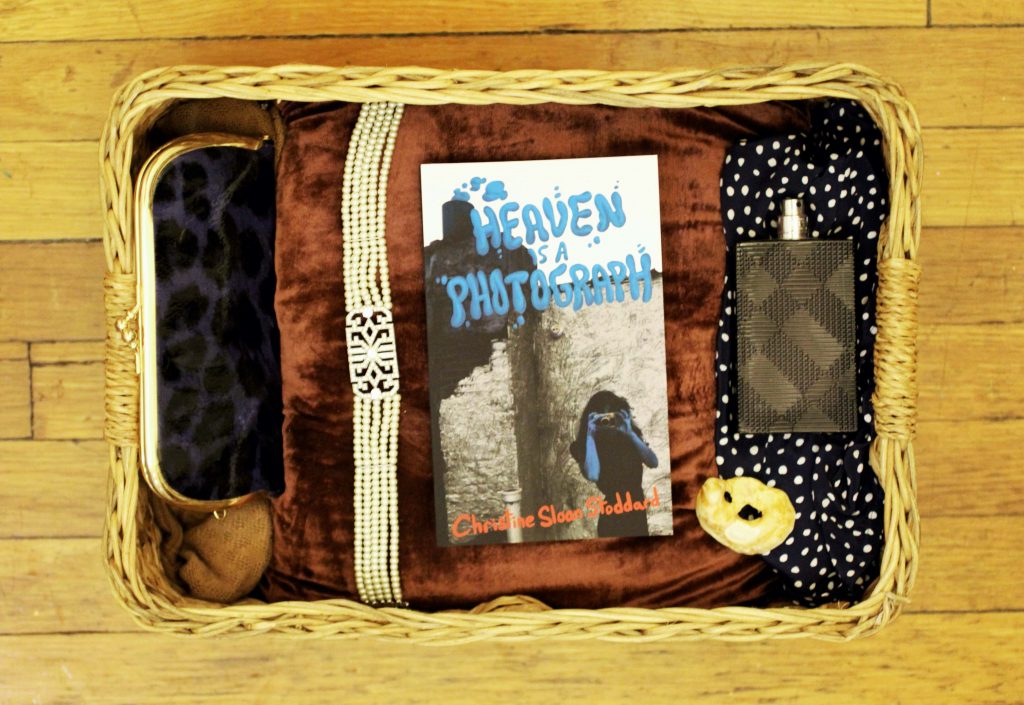

Sally Brown had the opportunity to interview Christine Stoddard about her recent book, Heaven is a Photograph (2020 CLASH Books), a book of poetry and photography exploring the relationship between an artist and her craft. In this very personable interview, Stoddard shares how the project came about, how the poems relate to her life experience, and so much more.

Your work seems to be autobiographical, even journalistically written. What’s your writing process like?

Not all of my work is autobiographical, and even that which is based on my life falls more into the realm of parafiction. That is certainly the case with Heaven is a Photograph. It contains elements of the truth but does not claim to be a journalistic representation of my life. Not even remotely! That’s why it’s poetry and art photography versus a memoir. It’s a creative interpretation and expression of one aspect of my life. Even with that admission, many details have been exaggerated or fictionalized. I am more aligned with my protagonist’s soul than I am with her exact, literal life experiences.

With that in mind, I am largely uninterested in commenting upon what’s true or untrue or “truthy.” Here is one exception: while my father is a director of photography for news and documentary, he has not worked in war photography in decades. When he did, he worked on television projects, not still photography. This may sound like a technicality, but this book, in both its narrative and format, is about still images, not moving ones. If Heaven is a Photograph focused on television (or film and video more broadly), it would be a different book. It upholds the beauty and power in capturing of moments, not a compilation of moments. Though I wrote the manuscript a couple of years ago, I am pleased it is coming out now and not as soon as had been originally planned. The COVID-19 quarantine period has reminded me to delve into stillness and all its lushness. Stillness and its demand that we pay attention is one of my favorite aspects of photography.

Certainly, journalism was at the forefront of my mind when I wrote Heaven is a Photograph. After all, the battle between art and journalism is a central conflict in the book. I do have the unique background of being both an artist and journalist and, as the daughter of a journalist who went to art school, I have had conversations about what distinguishes art from journalism for as long as I can remember. This question of art versus journalism hardly seems relevant to the world of traditional studio art—painting and sculpture—but the definition of art has expanded. Now photography, film, video, audio, performance, digital media, and social practice have joined the world of studio art. This is true anywhere art is found: museums, galleries, academic spaces, the internet, and nontraditional physical places (though the line between physical and virtual has blurred even more during quarantine). My MFA program at The City College of New York was so interdisciplinary that I made everything from ceramic sculptures to video diaries to acrylic paintings. Having worked for newspapers and magazines, I can say with confidence that some of my MFA photography could have been published in mainstream journalism outlets.

Heaven is a Photograph began as a conceptual art project that I made during grad school under another name. The original form was a website. The reader would scroll through poem by poem and only reveal photos by accidentally clicking hidden hyperlinks. They did not know the project contained photos unless they discovered one. In testing the project with classmates, I noticed that once a reader found one photograph, this piqued their interest to hunt for more. I designed the website this way to reference the protagonist’s own hidden photography practice. My professor for the course was Brian Droitcour, an editor at Art in America.

My writing process for the book was pretty organic, and that’s typically how I work: I write things that have been brewing in my head for a while (sometimes years). Creative writing doesn’t usually take me long for two reasons:

- I have usually done most of the thinking in my head and might have brainstormed in non-writing ways, such as sketching, sculpting, or, yes, photography.

- Journalism has trained me to be fast.

Because I was initially concerned about meeting class deadlines for the first iteration of Heaven is a Photograph, I did have to work fairly quickly, and I’m glad my classmates held me accountable for that. Every critique we had to show notable progress on our project. It wasn’t that different from writing on deadline for a journalistic outlet and being held accountable by your editor and readers.

A couple of your poems deal with both your chosen college/career path (photography) and relationships with men (your father, your ex-boyfriend). Is it accurate that those relationships influenced this choice and, if so, how?

This part isn’t autobiographical, either. It’s my protagonist. I have worked in both art and journalism and still straddle the line in some of my personal projects as well as for Quail Bell Magazine, the publication I founded in college. My hard news experience began in college, most notably when I worked in the multimedia department for WashingtonPost.com. Mostly, though, my journalism experience has been in features writing, which aligns more closely with my literary interests and ambitions. There’s also no college ex-boyfriend. I married my college boyfriend, David, and continue collaborating with him on creative projects. But my tensions with certain men, like my protagonist’s, have been and remain very real. Suffice it to say that art and journalism are both fields that attract narcissists and historically value male talents and perspectives.

In a broader respect, your experience reflects many women artists’ experience as they have to convince themselves of the value of their perspective and chosen career path in the arts (“there creations were not baptized creations…was i allowed to be like papa?”). Even in 2020, do you think this is still a feeling many women in the arts share?

Definitely. I can’t even count the number of times I’ve heard this. Recently in quarantine, I’ve been working on a blog series for the Textile Arts Center in New York City and have had to interview all of the participants in the artist-in-residence program. Most of them have expressed relief about working in a female-dominated space, or at least one with strong female leadership.

I do think that white, middle-class, American-born women have achieved a degree of representation in the art world that other women have not. It’s not like I’m the first one to note this, either. I would like to see more non-white women represented in exhibitions and spaces for female artists in ways that are not othered, exoticized, tokenized, or only special “diversity” occasions.

Regardless of racial, class, or cultural background, many of the women artists I know fear sexual harassment and resentment from other women. Probably in New York City more than anywhere else, there are predatory patterns among curators, editors, producers, and administrators that are unacceptable. The mere insinuation that my work would be considered for an opportunity in exchange for sexual favors is unacceptable. The number of times I’ve had male taste-makers prioritize engaging with me (or attempting to) over engaging with my work is unacceptable.

In a few of your works, you mention that you don’t “capture” photos, but that you “give” them. What does this mean to you?

I consider photography a gift. You, the photographer, are gifting the viewer a moment in time and an insight into your view of the world. Maybe they didn’t ask for this gift, but you’re giving it to them, anyway.

In “Maker” you reveal a lot of your process of gathering found objects to pose for some of your photos. What brought you to gather objects, how do you select/pose, and why do this as opposed to unposed? To me, your influences might range from Francesca Woodman to Betye Saar to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven to Kathy Vargas. What artists/photographers have influenced your work?

My parents definitely influenced my process of gathering found objects, which I use to pose in some photos but also to make sculptures and installations. (A good recent example is my installation, “Rabbit’s Storytelling Throne,” at the Queens Botanical Garden.) My mother grew up in El Salvador, which is one of the most impoverished countries in the world. Living during the civil war made her especially resourceful. My father struggled with neediness as a teenager and young adult. He lived in Manhattan in the 1970s, during a time when New York City went bankrupt and the Oil Crisis Recession took hold of the US, Canada, Japan, and a few other countries. Not too long after that, he witnessed poverty and wartime as a journalist in the Caribbean and Latin America. I was taught to reuse and reimagine from a young age.

I think all of your artist references are fair; I might also add Romare Bearden, Joseph Cornell, Sally Mann, Shelley Jackson, Simón Varga, Susan Meiselas, Frida Kahlo, Kukuli Velarde, and Fernando Llort. But it’s also hard to pinpoint all of my influences. I don’t usually make work that’s a direct homage to any single artist, except sometimes in small experiments that I consider more exercises than anything. There are many intersecting and cumulative influences.

The truth is I look at a lot of different art, design, and media. I grew up in a bicultural home with a mother who loves the arts and a father who went to art school and became a journalist. When I was little, it wasn’t unusual for us to spend family time looking at Victorian art books, watching Mexican soap operas, or listening to Jazz and R&B. Because we were near Washington, D.C., my parents often took my siblings and me to the Smithsonian museums and cultural events. We went to hole-in-the-wall galleries and art centers throughout Virginia and Maryland. The Torpedo Factory in Alexandria, VA, was one of my favorite local spots as a kid. We traveled a lot, especially by RV once I reached 5th grade. My father is a freelancer, which allowed a lot of flexibility in the summertime when we were off from school, and we drove to Maine and Florida most years. I had been cross-country twice by the time I was 17. We camped at a bunch of Native-American-owned casinos and let me tell you: the exhibitions and performances at those venues are top-notch. We also came up to New York City a lot and visited all kinds of cultural institutions. For college, I studied in Iowa and Richmond, VA, with workshops, study abroad, and research trips in Scotland, Mexico, and France. All of my work, even at that age, was in the arts and media. I moved to Brooklyn in my 20s, did my MFA in Manhattan, and worked a lot in the Bronx and Queens. Today my husband is a designer and filmmaker and almost all of our friends are artists of some kind. Throughout the pandemic, we have experienced or participated in so many virtual arts events, from illustrated lectures to theatrical performances, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. (Well, except in person, but that’s not feasible right now.)

In “Camera for Company,” you write “do not bring cameras to parties / people want freedom in their tomfoolery.” I’m guessing you must have experience with this. Do tell!

I don’t have a lot of experience with this because I’ve never been much of a party person (unless you count art openings, but those have always felt more like work events.) But I did bring a camera to a college party once and got a lot of flack for it. This was a decade ago before smartphones were so ubiquitous. Classmates told me they felt under surveillance. It’s shocking how social norms can change in just a few years because now plenty of college kids post party pictures on social media. That kind of documentation is often encouraged—dare I say pressured—from peers. In my case, I brought the camera because I wanted to capture the poetics of the evening. I wasn’t necessarily interested in individuals or even portraiture. I was happy photographing a SOLO cup in just the right light. Not so strange for art school.

In both Heaven is a Photograph and “Womb/Eye,” you use the color red frequently. What does this mean to you as it pertains to these works/photography?

Honestly, it’s mainly an aesthetic attraction. It’s primal, sexual, alluring. I have always been drawn to red. I’m sure I could trace that love back to some cultural influences, though they may be subconscious. There are my personal connections to tropical environments where red abounds. My mother is from El Salvador, and one of the popular art styles, La Palma, contains a lot of red. I grew up playing with trinkets decorated in this style. There’s also my connection to my Miami. My parents lived in Miami when they first got married, and we spent most of my childhood Christmases visiting my uncle there. Red is very Miami. I’m probably drawn to red as a feminist artist, as well, though I never felt intentional about red in that way. I know many feminist artists have used red for pieces related to the female body, but I often use other colors for my more body-driven work, at least these days. Like the cover art for my book, Belladonna Magic, is a dark purple (almost eggplant-colored) vulva. Or one of the first watercolors I made in quarantine features blue and pink lungs. There’s red in the piece, but it’s minimal (mainly visible in the COVID-19 viruses depicted).

You reveal in “Model Maker” that you modeled in college. What was it like to be on the other end of the lens? Furthermore, having discussed photoshopping in Heaven is a Photograph and “Radiance,” do you think the act of photo manipulation makes women feel lesser-than?

Again, my experience is not identical to that of my protagonist. I still do some modeling today as a way to pay my bills. New York City offers so many different kinds of modeling opportunities, and I’m lucky to have access to work I never would’ve imagined existed. Like, did you know that there are models for wholesale expos where bridalwear companies attempt to sell large quantities of their clothing to bridal boutiques and department stores? I didn’t until I saw a posting for this kind of work, and now I’ve done it. Even for live events, like a trade expos, there’s a lot of photography that happens.

I’d say that my understanding of photography has made me a stronger model, and it’s something photographers have remarked upon in the past. I know how to work the camera, and can usually anticipate a photographer’s next move. Generally, I’m more comfortable with women and non-binary photographers. I have worked with some very respectful and professional male photographers, but it seems harder for male photographers to avoid objectifying female subjects, no matter how aware or politically invested they may be. Unlearning social conditioning is something all of us struggle with, not just in photography and whether we realize it or not.

I have definitely had photos of me Photoshopped to the point where I barely recognized myself. That has certainly bothered me. In those cases, I have resented not having control over my image. That’s the loss of power I allude to in Heaven is a Photograph. That’s why it’s so important to have image-makers who are not white heterosexual cis-gender men, too. It’s not that men shouldn’t make images; it’s that they shouldn’t dominate the field.

How did your professor respond when you didn’t complete the photoshopping assignment?

This was not a real-life event. It was completely imagined. But I will say this: I am often frustrated by patterns and rules in art even though I follow many rules in my life otherwise. Conventional procedure bores me; I prefer to hack it and develop my own process. I use Photoshop, but I’m entirely self-taught and have no shame about playing or “doing it wrong.” At least I don’t have any shame anymore. Increasingly, I’m less concerned with the idea of “mastery” and more invested in my expression and communication. “Mastery” has too much heteropatriarchal baggage.

I first started messing around with Photoshop my senior year of high school. My art teacher had it and thought I would like it. That same year, I was accepted into a digital art program at nearby Marymount University. A professor there decided to offer free digital art instruction to local high school students and display their work at the end of the program. At least that’s how the program was pitched. There wasn’t much formal instruction at all. We ended up experimenting with Photoshop and learning through trial and error with the scanner and printer. It was glorious. I’ve relied on YouTube tutorials and friends since then.

I’ve always been an autodidact, and whenever friends ask for creative and professional advice, I urge them to teach themselves, too. It does not matter what the skill or field is. Don’t underestimate the reward for initiative and a good work ethic. When you care about something, that level of discipline is worth it. I especially urge women to teach themselves what they can using the resources around them. As my mother always told me growing up, our education can never be taken away from us. I take my education, both formal and informal, very seriously, in large part because I’m the daughter of a Salvadoran woman who’s vocal about women’s rights issues prevalent in her home country. El Salvador has high rates of teen marriage and pregnancy, but low high school and college graduation rates for women. My mother grew up without the same opportunities I have, and a lot of my success can be attributed to the sacrifices she made to come to the United States.

To any woman doubting her abilities and future prospects, I say this: go to the public library, read books, and scour the internet. You might not have the time or money for a degree program right now, but self-education is free. And there’s more to the internet than social media (though that can be used as a tool, as well.) I know the internet can be a terrifying place for women because of harassment, objectification, and lack of representation, but it’s also a gem.

In college, I earned degrees in Film, English, and Product Innovation and minored in Spanish, French, and European Studies. I really applied myself in and out of the classroom. Five years later, I began a two-year MFA in Digital & Interdisciplinary Art Practice. Even with all of that formal education, there was still so much I taught myself. My skills in web design, Search Engine Optimization, and grant proposals, for example, have not only paid my bills; they have complemented and enriched my art practice.

This is all to say this: I have learned that it’s often not enough to complete a class assignment; you need to figure out what lessons that assignment offers you, how you can apply them to your life, and how you can go beyond that assignment.

In “Unwritten Job Description,” you suggest that women are typically the editors while men are the masters/lead photographers. While, as we know, women have been slighted (to say the least) in the arts throughout history, photography is one art form in which women played a bigger role compared to other media (https://thefashionglobe.com/who-is-afraid-of-women-photographers). How has the fashion industry affected women’s ability to succeed in the art world as a photographer?

I don’t feel qualified to answer that question as it’s been posed, but I can address similar matters more directly relevant to the poem. I haven’t worked directly in the fashion industry, but I have worked or contributed to national women’s magazines (e.g., Cosmopolitan, Bustle, Marie Claire, etc.), many of which run a lot of fashion content.

“Unwritten Job Description” comments on the prevalence of women in the role of editor. In the magazine industry, an editor can be several things; there are many different kinds of editors and sometimes their roles overlap. In relation to photography, a photo editor is someone who edits the actual image and/or curates images for a story. Increasingly in digital media, the person who writes the story is often responsible for sourcing images from stock sites or rights-free databases. It’s becoming less common for magazines, even major ones, to hire photographers to shoot exclusive images for a story. Many magazines, again even major ones, have subscriptions to services like the Shutterstock, iStock, and the Associated Press. More and more, magazines use social media photography to illustrate stories, too.

In talking to other female writers and photographers, I’ve noticed the pattern that male photographers can often command higher fees than female photographers or just more paid work in general. There are likely two contributing factors here: most women have not been socialized to advocate for themselves in the way most men have been groomed since childhood. They may have trouble asking for as much money as their work deserves. We see this problem in other industries. This issue relates to confidence. There have been so many studies on male confidence versus female confidence. I think it’s not a stretch to say that many women simply don’t have confidence in their vision because they have not been socialized to believe in themselves the same way men have. There’s also the problem that male photographers generally have had more access to schooling, technical training, and professional opportunities by virtue of their male privilege in an already male-dominated field. Name recognition helps a lot in an image-driven field.

Men are more likely to get hired for those rarer and rarer magazine story commissions. Almost all of the female photographers I know who make their living primarily from photography shoot weddings, or other personal and social events, or shooting for stock photography. It’s important to note that stock photographers are not credited for their work. The stock photography company pays them for the image or, increasingly less commonly, commissions them to shoot a photo package that the company then buys from them. They sign over all rights to their work and the magazines that run their photographs do not run their names because the photo companies don’t provide that information. Many of the female photographers in my life have transitioned to the role of photo editor because it’s hard for them to make a living from their photography alone.

In a few of your works, you reveal an inner child challenged with failure: “never victorious / except behind a camera.” How do you work your way through such thoughts? What advice would you give to aspiring photographers who may be unsure of themselves?

I am still not as confident in my work as I wish I were, though I am slowly learning to believe in myself more and more. To create without fear will probably always be a challenge. But I can almost see my timidity decreasing as a I review photos of past works or studio documentation dating back to 2017. That was a pivotal year for me, and I have become bolder every year since then. A lot of making has been the answer for me. Extensive experimentation and trial and error have lowered the stakes for each stab at something. My advice to photographers who may be unsure of themselves is to go for it. When I was in college, an older friend who told me that if just 10% of what you make is “good,” the pain and effort will be worth it. I have spent my early adulthood holding fast to that advice. Trust in the process and just keep making.

All images from Heaven is a Photograph by Christine Sloan Stoddard, available from CLASH Books.

Christine Sloan Stoddard was born in Arlington, VA, to a Salvadoran mother and New Yorker father. While a student at VCUarts, she founded Quail Bell Magazine, a place for real and unreal stories. She also founded its parent company, Quail Bell Press & Productions. Since then, she has worked as an author, artist, filmmaker, and theatre-maker. She has shared her creations and talents at the New York Transit Museum, the New York City Poetry Festival, the Queens Museum, Theater for the New City, the Kennedy Center, and beyond. She is a Table Work Press award-winning playwright, Visible Poetry Project filmmaker, and a Puffin Foundation national emerging artist. She holds an MFA in interdisciplinary art from The City College of New York.