Dressed in a medical gown, I sit in an uncomfortable plastic chair behind a foldable cloth and metal partition. I stare at the stains on the partition, trying not to imagine their origins. A blonde man in a bright red shirt decorated with blue leaves towers over me, needle poised. He complains about my tiny veins. He removes his gloves with exaggerated flourish, deeply sighing as he does. Bare-handed, his skin touches mine. He uses his index finger to press against the valley between my upper and lower arm. His mask hangs down over his nose as he rolls my tiny veins back and forth. The first nurse to greet me was a small woman with brown skin and thick-rimmed glasses. I was comforted seeing another woman, one that reminded me of my madrina. But she took two steps backward and let the man in the bright red shirt take over. I try to make eye contact with her now, but she won’t look at me.

It’s my first breast MRI. I witnessed my mother undergo the same test when she was still alive. When she was still in the phases of early detection. The numerous women in my family who have lived with and those who have died from breast cancer are always a specter in the shadows of my heart and mind. Since I was 30, preventive care has been on every doctor’s tongue. Even my endocrinologist and gynecologist have joined the chorus. But it’s not necessary for them to remind me how much the generations of women in my family have lost to cancer. It’s not something I could forget.

And I don’t like to be touched by strangers, especially when I’m not expecting it. I wish there was some form of questionnaire before all of this, some way that I could have communicated my unease. I want to tell the man in the red shirt, Put your gloves on and pull up your mask. I want to tell him, Don’t fucking touch me. I want to tell him, Men make me anxious. But I don’t tell him anything. My tongue lies heavy in my mouth, resistant to my brain. I wonder if he hears my erratic heartbeat. It feels like a battle cry from my body’s histories. I tremble. The man confuses my shaking for low blood glucose, commenting, Haven’t had much to eat today, huh? I don’t respond, not even when he asks the woman in dark-rimmed glasses to call another technician, T. He’s the only one that can get the IV in veins like these.

By the time T arrives, the man in the red shirt has inserted and removed two needles from my right arm and another needle from my left. He’s set the IV tube on top of the dirty partition, waiting as T puts on gloves. I exhale, hoping T can help. She’s got stubborn veins, the man in the red shirt says. T nods, his skin glistening with sweat. He uses his index finger to poke at my right arm, searching for veins. Despite his mask and mine, I can smell plaque buildup in his teeth. I resume holding my breath, focusing on something else. I think she’s dehydrated, the man in the red shirt says. T’s eyebrows come together. I don’t think so.

The man in the red shirt walks to my other side and tries to hand T a needle with his gloveless hand. T shakes his head, gestures to the clean needles. I clear my throat, try to thank him, but I can’t. My anger with myself for staying so damn silent burns my cheeks, acid twinges my gut. The man in the red shirt says, How far was your drive? I’m guessing you wouldn’t want to come back another time? I shake my head. I want to tell him it was a two-and-a-half-hour drive to get here. This place was thirty minutes farther than the facility closest to my home, but my new genetic oncologist recommended this place. She told me they were great with preventative care.

When T finally manages to get the line for my IV inserted, he nods, pats my forearm, and leaves. The woman with glasses guides me to a dark imaging room where another woman is waiting. Standing in the new room, I realize how much my gown smells of stale chemicals. They ask me to remove the gown and place my breasts in the opening on the table, face down. I hesitate. It’s alright. The technician’s waiting outside; he can’t see in here. We’ll cover you with a blanket as soon as you’re in position.

Climbing onto the table, blood drips from the IV in my arm. I’m sorry. The whisper surprises me. They’re the first words I’ve uttered in over an hour, and they’re an apology. The woman without glasses cleans the blood with an alcohol wipe, saying nothing.

The other woman with glasses reads my chart. So your mother died of metastatic breast cancer?

I pause on my hands and knees, nearly naked. I’m not prepared for the question, nor am I prepared for how it guts me. I want to ask her why they waited until now, when I’m naked and vulnerable, to ask. Instead, I nod, whisper, Yes.

I try to focus on hiding my body on the MRI table. As I lean forward, I realize the opening for my breasts is located at my chin. They’ve set it too long for my torso. The woman without glasses starts adjusting it. Oops! Tiny little thing, aren’t you?

I want to ask them to stop referring to my body as tiny. The last thing I ever want is to talk about is my body, especially now, in this moment, as the woman with glasses reduces my maternal family history to cancer diagnoses and the woman without glasses touches me without warning. The woman with glasses continues: And your grandmother? Total mastectomy? She’s still living?

Yes, I answer. Remission.

And your… she pauses, I’m assuming to refer to my chart, but I can no longer see her because my forehead is pressed into the headrest and the woman without glasses is guiding my arms into a streamline position above my head, as if I’m about to dive into a pool of water. Your cousin. 38? Is that right? Is she in remission?

I can feel blood dripping down my arm. My fingers tingle from the new position and I worry I won’t be able to stay still like this for the 45-minute scan. I feel the rush of tears threatening. It angers me. I don’t want to discuss any of this right now. My thoughts make me unaware of my surroundings, something I rarely allow myself to do. My forehead is pressed to a headrest; I cannot see anything. I’ve lost my sense of place. I’ve lost my grounding. The woman without glasses touches me again, unannounced. As her hands adjust my left breast, a whimper escapes my throat.

I’m sorry? The woman with glasses keeps pressing. Does she think I lied on my intake paperwork? Why’s she doing this?

Yes. Everything in my chart is accurate. I verified it yesterday during my electronic check-in.

My voice is shaky. I know they can hear it. The woman without glasses confirms that I’m positioned and ready. The questions finally stop, and my test begins. I’ve never been more grateful for the loud thumping of the MRI machine.

*

After the MRI, I can’t give words to how I feel. I know it’s not one thing. It’s not just my family history. It’s not just my aversion to touch. That test made me feel exposed in ways I never expected.

My husband stands from his chair in the waiting room and smiles, lines appearing around his eyes. All set? He reaches for the bag on my shoulder.

I nod.

He tries to wrap his arm around my shoulders.

I wince.

His eyes change, lightening from their usual hazel-brown to green. His worrying eyes.

I’m okay. I don’t mean it. The words are for him, not me.

We sit in the outdoor dining area at Chipotle. I slowly eat my veggie burrito bowl, one small bite after another. I don’t speak. I sip juice. Watch an elderly couple share a burrito bowl and soda. They eat silently too, the man pushing the sour cream towards the woman and the woman stirring it into her rice, beans, and meat.

Hey. My husband tries to hold my gaze. Face serious, his mustache twitching atop his pursed lips.

I’m just tired. Ready when you are.

No shopping?

Because we live in a small valley surrounded by mountain passes, shopping is limited. I usually hit a few stores after medical appointments. It was a tradition started when my mom had to travel for treatment. Today, I don’t want to do anything.

I sleep on the drive home, allowing my husband to believe it’s the contrast lingering in my body. It’s not until we arrive that I greet my teenage daughter before making my way to my bedroom, locking the door, crawling into bed fully clothed, and cry. I’ve mastered the silent cry, allowing my body to heave and wrack soundlessly.

A memory from when I was a young girl, right around seven or eight, resurfaces. I remember how I sat in the back seat of my family’s brown Chevy Blazer as we made our way home from a trip to the city. I don’t know where we were, but I know it was a stretch of barren interstate between city and our home, the San Luis Valley. I was sleepy, but often resisted sleep for fear of missing something. I’d been chewing a piece of gum and it had lost its flavor. Thoughtlessly, I cracked the door open to throw out the gum. It was a childish moment and as soon as I heard the click, I realized my mistake, pulling the door shut. My heart thudded in my ears—I was afraid. My dad pulled over, turning around from his place in the driver’s seat: What the hell’s wrong with you? I felt a burn in my throat and in my groin, peeing myself as he yelled. I was too afraid to ask to use the restroom, to ask to clean myself; instead, I rode home in clothes soiled by my own urine, digging my nails into my palms, chewing on my cheeks to keep from crying.

I realize I have the same feeling in this moment, that small child feeling ripe with inexplicable fear. I want nothing more than to remember something good, something to make me smile or laugh. Instead, I feel like I’m floating, weightless and out of control.

*

After the MRI, I start dreaming of the imaging room. I feel the coolness of MRI contrast entering my veins. I can see inside myself. I watch the thick fluid replace me, plasma parting like the Red Sea from my catechism lessons. My dream-self witnesses foreign movement inside me, witnesses as my body yields, silently allowing the intrusion.

When I wake one morning, it’s still dark outside. I scroll through emails. In one of the many newsletters I receive, I encounter an article titled, “Lying on the Floor Can Help You Feel More Grounded, According to Trauma Specialists.” I click on it. In the article, Erica Sloan writes about being grounded and its relationship to control and why scientists correlate it to trauma therapy, concluding the article with her own experiences lying on the floor daily. Before I finish reading the article, I find myself unrolling my yoga mat in my office, stretching my body out on the mat, back pressed to the floor. My thumbs and forefingers form a diamond around my belly button.

I don’t know how to reclaim my body. I don’t know how to sleep at night, how to sit in an examination room without feeling obligated to vocalize my worries and my trauma before every medical appointment.

I try to notice my surroundings. I notice the tension in my body, soreness from exercise and stiffness in my shoulders. I feel cottony air above my hands. I smell a mixture of sweat, disinfectant, and synthetic foam from my mat. Non-judgment feels nearly impossible. Even here, on the floor, I’m judging everything, including my inability to be stronger.

Grounded. Long after I rise from the ground, the word remains with me. A quick search on the online version of the Oxford English Dictionary reveals a series of definitions and etymologies. From the soil that gives us life to the more modern definition of emotional stability, it’s a word deeply woven into the fabric of the English language. Still, the term was not used in association with mental stability until the late 1950s.

Grounded. I scan my memories, trying to identify my first exposure to the word. The only thing I can remember is the term being used as a form of punishment: You’re grounded. The word meant I was to remain at home—no friends, no adventures, no fun. Sometimes, despite my stoic behavior and complaining, being grounded was an unexpected reward. I didn’t have to pretend with friends. I could curl up on my bedroom floor and read without explanation, for I was grounded. What else could I do?

The word did not otherwise have much meaning in my youth. I was raised to sense energy and respect life, but concepts like being grounded emotionally or trauma were nonexistent. It was not uncommon to hear a family member comment that depression was a white problem, an implication that feeling (or not feeling) emotions was a privilege that many of my family members assumed we didn’t have. I grew up believing that anxiety, depression, and even trauma were just that—privileged problems. Talking about emotions and feelings was a sign of weakness. Hell, writing this essay is a sign of weakness, a calculated move to get attention.

But my mom talked often of being in unity with the earth and with the universe. She taught me to value all life and to respect all living things. My dad kept a vast garden despite our cold climates and deep freezes, meticulously caring for his plants. He reads books on wild plants in our area, learning about what to consume for each ailment, something my mom, and his mom, simply knew. My entire life, he’s lectured on how to survive in the wild, on what plants are edible and what’s poisonous. As I’ve matured, I’ve stopped laughing at his refrain: If a deer eats it, you can too. After a hunting trip, my dad, mom, brother, and I cleaned, cut, packed, and preserved nearly every part of the animal. We wasted as little as possible and consumed the meat in our daily meals. In many ways, they taught me how to be grounded in the earth of my home.

But I want to be grounded in a new way, in the way I realized on the floor before dawn. I want to be grounded in this new definition that I’ve encountered in discourse about healing and mindfulness. I want to be grounded and in control.

*

All cancer is genetic. Or at least that’s what the genetic oncologist tells me during our first phone call. If there’s a phrase that makes me feel out of control, it’s this one.

She starts the call by asking what I understand about cancer and cancer prevention. I spend the next ten minutes summarizing my knowledge of cells and stages and invasive ductal carcinoma. She interrupts me. Says I’ve clearly done my research. I want to tell her how many times I sat by my mother’s side at her oncology appointments, how many times I helped my grandma understand her test results, how many journals on cancer research I read in waiting rooms and chemotherapy suites. But there’s no time. Before I can respond, she explains the results of my risk assessment, despite my already knowing my percentage of likelihood. She explains genetic mutations that increase the chances of different cancers. She tells me that genetic testing works best when the person has already tested positive for cancer. Would my grandmother be open to genetic counseling? When I respond that my grandma’s battling dementia, she finally agrees that moving forward with genetic testing is the best choice.

I receive the test in the mail. My husband washes his hands and holds the return package open for me while I spit until I’ve produced enough to hit the fill line. I message the oncologist in my patient portal as soon as I mail my saliva sample to the testing facility.

She responds almost instantly: Thank you. We’re going to do everything we can to prevent another generation of cancer in your family.

I’m not sure I believe her but hope blooms in my chest. I feel like I’m in a constant state of spiraling and remembering. Sometimes I wish people would ask me for my mother’s name or her favorite book. I wish people would ask me what she was like before cancer defined her life. I wish each doctor would stop repeating the same numbers and statistics and instead ask me something I learned from the generations of women in my family.

Lory. Her name was Lory. And her name—first, middle, and last—had histories too. Ones that had nothing to do with cancer.

*

Still consumed with the notion of being grounded, I decide to take a mindful writing course. On the fourth session, the instructor guides us through a body scan, asking us to notice. She tells us she’ll avoid our genitals as they might be a trigger. I snicker without meaning to. I consider explaining that a body can hold trauma anywhere. It’s the most unexpected locations of the body—and life—that trigger: an MRI scan that reminds you of what you’ve lost, the touch from a hand you can’t see. In that machine, I was taken back to the scent of peppermint schnapps and a slow-burning roach, a moment from my youth that I try to forget. I was taken back to my mother’s illness. I was reminded of every time I felt like my body wasn’t mine. Triggers are not localized, I want to tell her. But I don’t.

Since the MRI, I’ve been researching trauma-informed medical care and medical education (TIME). Some, though not all, medical schools are implementing required training on how to treat patients who have a history of trauma. I skim article after article, thinking, Don’t we all have some type of trauma we’re dealing with? Shouldn’t it simply be referred to as medical care? Still, I find each study to be comforting, intrigued at how medical jargon can distance me from myself. I don’t believe that one can ever become an expert on trauma because it’s complex and personal, yet I’ve observed that once trauma is alluded to in a social setting, others deem that person an expert. They want to understand. But after my experience, I can’t help but wonder why all patients can’t be treated with care that’s driven by understanding. I’m tired of people feeling like they’re entitled to know more than I’m willing to share in exchange for their compassion.

The instructor’s voice shatters my reverie. Focus on the palms, she half-speaks, half-chants. I make fists. Opening, closing. I flex my fingers, trying to concentrate on my body. Instead of contemplating my hands, I remember my first endocrinologist. Upon meeting me for the first time, he walked in and studied my chart before acknowledging me. He read off facts that he deemed relevant—my symptoms, my age, my height, commenting on my weight: Skinny- minnie! No problems here. I’d been experiencing concerning bouts of dizziness and disorientation, unexplained weight gain. I would later learn that my symptoms were related to anxiety, grief, and an imbalance of hormones due to an endocrine issue. Before I had doctors willing to parse through my symptoms with me, I encountered many like the endocrinologist who didn’t take the time to make eye contact before concluding I was fine. I had doctors tell me that my blood tests were normal. They told me I was therefore healthy, that I’m just hypersensitive, that I needed to eat more carbs, that I needed to eat fewer carbs. I was told I was simply experiencing a vasovagal response without explaining how it could be related to triggers or anxiety, without questioning if it might have been triggered by the loss of my mother. I had a doctor laugh at my nervousness when she delivered abnormal results from an MRI, smirking and saying, It’s not a big deal. I had a doctor deep-sigh, pull up his pant legs, and sit down before telling me about a patient with real symptoms that warranted concern so I could recognize that my symptoms didn’t require a visit to him.

By the time the mindfulness instructor guides us to scan our ribs, I realize that it took me three years and a four-hour drive to find an endocrinologist that has been able to help me recognize my concerns are valid. She’s the first doctor that has ever asked me for my opinion on treatment options. The first doctor to ask about my daughters or my writing. I’m seething. I want to ramble about malpractice and mistreatment to my mindfulness class. Tell them about the time my mom was told that she wasn’t pregnant with me but had a brain tumor instead. The time my childhood dentist spanked me for crying and misbehaving. I could talk for the rest of this class, I realize. But I won’t. I don’t want to rant. Always, I don’t want to seem too angry.

But I am. I’m angry that my body continues to be a commodity—a thing for exploitation and politics, a thing that’s never mine.

The body scan continues, my palms upward and eyes closed. My mind’s racing. I’m not sure if I want to scream or cry. I’m surprised when my heart aches as if it’s swelling, on the cusp of implosion. Sweat dampens the cloth beneath my armpits, slides down my temple and into my hair. When it’s time to write, I don’t write about past traumas, where my muscles are tight, or even how I felt during the body scan. I don’t rant about my medical care. Instead, I fill pages of my notebook with memories of my first breast MRI.

My results were normal. Yet, for months after my scan, I couldn’t sleep without interruption. So, I write about control. I write about my aching forehead, pressed into the headrest as hard as I could. I write about the need to control something, if even the pain I felt in my forehead. I write about refusing to cry. I write about the feeling of blood dripping from my IV and down my elbow. I write about my willingness to accept the darkness of the machine’s tunnel if it meant I no longer had to endure unexpected touch and invasive questions.

In the last line of the entry, right before my instructor closes class, I scribble: I need the hurt because it’s easier to understand—to contain.

*

During our weekly taco lunch date, I pour salsa over my tacos before glancing up at my husband.

So. I’m kind of obsessed with the idea of being grounded…

He sets his taco on his plate, attention on me.

I clear my throat. Six months ago, I had a breast scan that triggered shit I still don’t fully understand. I gesture with my arms, emphasizing the size of the void. I’ve been researching grounding techniques. Trying to figure it all out.

And?

And I’ve been trying this grounding technique I read about. I lay on the floor. Like literally. To ground myself.

He laughs.

I continue. Yeah. I know. Poquito joins me, purring loudly while I meditate or whatever.

My husband lifts his taco. Chews. Swallows. Finally, he shrugs. I’ve always thought being grounded is kind of like belonging. He says this as if it’s the most obvious connection fathomable.

I don’t know how to respond. Staring at my calabacita tacos, I contemplate belonging. How did I never make this connection on my own? Of course it’s about belonging. It’s about being safe. That’s what control is all about.

As I eat, I search my memory for the last time I felt as if I belonged. Frustrated, I drop my taco to the plate. It falls open, guacamole, cilantro, and onion scattering onto the table. I sop up my mess and glare at my husband, challenging him: Do you think we have to belong to a place? Or can it just be a mindset?

My husband watches me. His silence makes my hands shake. I wonder if he heard me. If he missed something I said. Finally, he mutters, I think it just means we’re part of something. Like we’re not alone.

*

My mother’s last years of life were not just about tests. Before the cancer metastasized to her brain, my mom spent her summer days at my house. I picked her up early, usually right before 7. She could still talk at this point. In fact, she spent almost all day talking, trying to get everything out—her life, her regrets, things she worried I would forget. At precisely 11:45, my grandma would pull into my driveway. Despite our knowing that she’d be there, she always rang the doorbell rather than letting herself in. My mom and grandma would huddle together on the couch, lunches I prepared in front of them, awaiting the opening scene of The Days of Our Lives. It was time for their soaps. Despite my constant critique of the show, they always made me sit down with them as they made predictions and gossiped about the characters in Spanglish as if they knew them intimately. At especially dramatic scenes, they rolled their eyes while loving the petty drama of it all. My mom’s willingness to watch the show surprised me, for, like me, she found soap operas to be silly. But it was an unexpected ritual between three women. I could have cared less about Victor or Marlena. I loved being part of something, and I think my mom and grandma did too.

I choose to be part of something. I choose to belong in memory, to a time when my family’s genetic history has not left me feeling alone.

Finally, nine years after my mom’s death and months after my first breast MRI, I turn on the television at 11:45 on a snowy weekday a few days before Christmas. My daughters—now young women—are partaking in an annual ritual of making tamales and Christmas cookies at my mother-in-law’s house. I mute the commercials, brew tea. I welcome intentional silence. A silence I control. At the title sequence, I start sobbing. I wail, body shaky and desperate. I allow myself to mourn a generational tradition that doesn’t lurk in our cells. When my body steadies and my tears dry, I unmute the show. I watch TV and relish a memory that no doctor, no cancer, and no trauma can take from me.

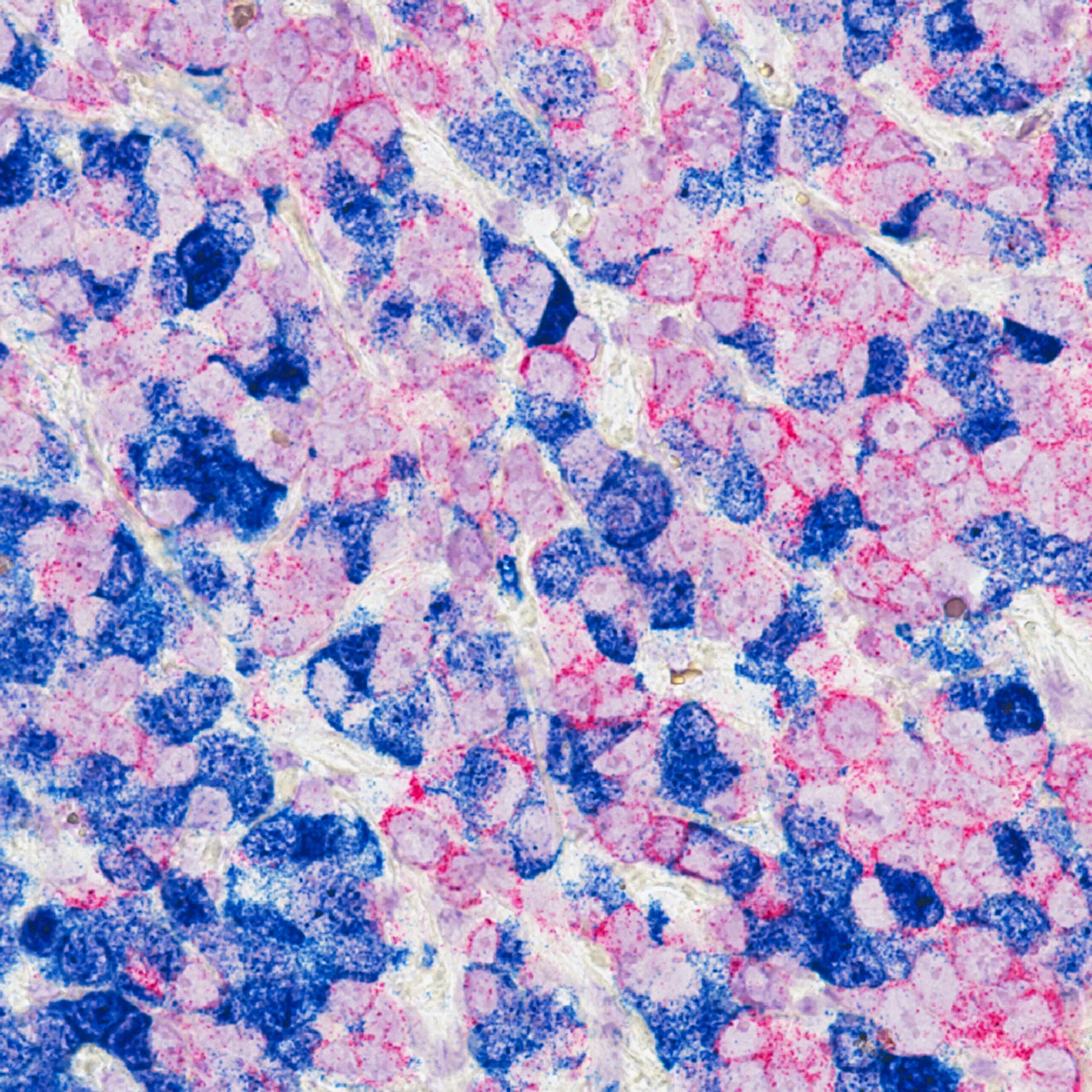

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash