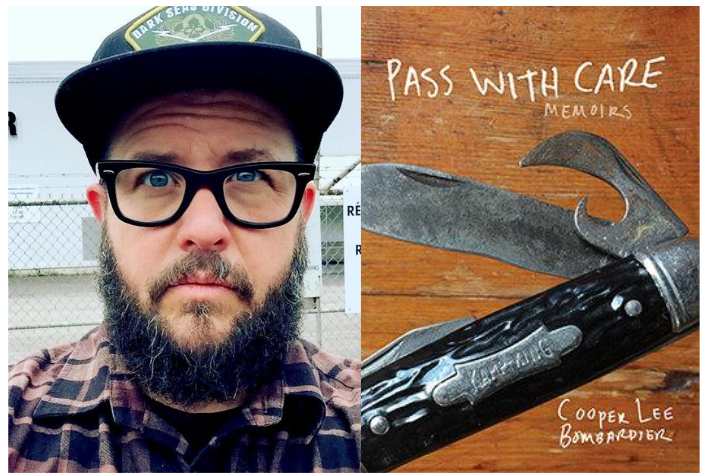

Cooper Lee Bombardier is a transgender writer, artist, and activist. In this interview with Alexis Garrett, he discusses the making of his debut memoir-in-essays, Pass with Care, which traverses terrain from working-class New England to the queer punk scene of early-nineties San Francisco.

In your memoir, Pass with Care, you combine personal essays, poetry, and lyrical nonfiction to create a modern blend of genres and storytelling techniques. This isn’t easy! Each of these elements has its own unique structure and personality. What’s your process for shaping such a diverse collection out of these very different forms of art? How do you maintain balance while juggling these genres?

I see all of the pieces in Pass with Care as sharing the same genre: creative nonfiction, but under that rather broad arch, I explore masculinity, class, gender, and trans as a verb by using various formal structures and constraints. For me it’s not so much of a juggle as much as it is the question I want to ask or the approach I want to take with certain material. Some forms or shapes enable me to interrogate a subject that I’ve written about extensively in a completely different way, for example in “A Trans Body’s Path in Eight Folds,” I eschewed using any gendered words or pronouns at all except for “trans,” and I wanted to constrain the piece into eight short segments. Taking out all pronouns, including the “I,” allowed me to experiment with subjectivity in a different way than I might in other essays in the book where I meet questions about gender and embodiment in a manner that could be seen as more head on. Some of the pieces I’d approached with a set of constraints at the outset, while other pieces seemed to direct me toward form. For example, “Half as Sensitive” initially wanted to be a deeply researched and reported feature type essay, but the more I worked on it, the more it spoke to me of wanting to explode outward into fragments and threads, and the more I wanted to weave my subjectivity into my research and exploration of animal experiments at a nuclear reservation. The process to me felt like watching a milkweed pod explode and send its seeds out into spiraling air currents. I wanted to chase down every seed. Genre’s a funny thing, anyway, especially for a trans writer. It feels like another social construct that benefits capitalism above anything else.

The known history of trans-authored memoirs is a short one, unfortunately, since it gained attention only in the last century. But even as these narratives surfaced, the amount of copies sold didn’t translate to widespread acceptance of the trans community. What’s your perspective on this relationship between curiosity and genuine support?

We are in a beautiful moment where more trans people are able to tell their own stories and reach broader audiences than ever before. And yet, visibility does not seem to directly correlate to an improvement of life quality, increased rights and protections, equality, and justice. So, one’s interest and support of trans creative outputs hopefully should influence how one is voting, and where one centers their activism, financial support, volunteer work, and how they enact trans-welcoming space in their workplaces, schools, businesses, neighborhoods, friend circles, and more—especially for trans women of color, who remain a wildly vulnerable demographic despite perhaps more mainstream visibility than ever. Also, I challenge non-trans readers to read at least three books by trans authors for every book read about trans people by a non-trans author. It makes a big difference in shifting the non-trans gaze and learning to see us as authorities and experts on our own lives and experiences.

As a queer writer, you have a personal relationship with the themes of your work. In recent years, many fiction writers, both within and outside the queer community, have included more diversity in their stories, including trans characters. What’s your opinion on writers who create trans characters without the intimate knowledge or understanding of the community? What are your thoughts on modern writers stepping outside their cultural experiences for the purpose of inclusion?

As a writer of creative nonfiction, I use my own lived experiences as the material of my work. Of course, this means that I also write about other people who are not me, because I do not live in a vacuum. Writing, much like gender, is relational. It is important to consider the fact that we live in a world filled with other people whose lives and desires and struggles and grievances and joys are just as real as our own. But there’s countless examples throughout all of English lit where the “other,” those who are “not me,” are but a prop, a device, a foil—used to shore up the “real” storyline of the unmarked, normative body. It is important, if one is a writer of dominant social identities and privileges, to consider how that power differential is manifesting in one’s work, and if one is entrenching harmful tropes. Ultimately, publishing is controlled by and perpetuates a dominant narrative of white, cisgender, heterosexual, male, able, wealthy bodies as the authority on everyone else, and so the problem here is that it is likely that a cisgender person’s truly shitty rendering of a trans person in literature will still gain a larger readership than the most erudite, lucid work produced by a trans author. If you are a non-trans writer who wants to write a trans character, or a cis nonfiction writer writing about trans lives, I think it is important to ask yourself why. What’s your skin in the game? What are you doing besides using trans people as a metaphor for your own story?

Location and time are important elements of Pass with Care. You explore various environments across the United States as well as your personal growth over the course of two decades. This sense of motion and maturity runs parallel to the queer community, which perpetually changes and redefines itself as we gain a deeper understanding over time of queer identities. As a queer woman myself (who recently moved from a Southeastern state to the Pacific Northwest), I’m especially fascinated by the major cultural differences among communities separated by time, distance, or both. Having observed decades of its evolution, what does it mean to you to be part of such a kaleidoscopic community?

I recently wrote an essay on queer peripatetics and the liminality of borders for a book called Home is Where You Queer Your Heart, coming out in 2021 from Foglifter Press. I moved around for love and art to various American queer meccas, large and small. All of these places also spoke to me as landscapes, and I was as much drawn to the natural beauty and diversity of environment, as well as the vibrancy of each of these places as centers of creativity and innovation. And yet, I’ve travelled around the US extensively, I’ve been to every state except for Alaska, and I’ve witnessed queer people making vibrant lives happen for themselves in all kinds of communities. As a young person, I had to go as far away from where I was from before I ever felt like I could go home and not feel my personhood swamped by the normalizing expectations I clearly never would live up to. In occupying an ontological position as a white queer trans man and artist, I also have to consider my implication in forces of gentrification, and how my presence has contributed to the eradication of the very diversity that drew me to neighborhoods in which I’ve chosen to make home, and how that cycle also has ejected me as someone whose presence has contributed to making a place no longer affordable. It’s a complicated issue that I am still writing and thinking through and acting on, for example, through actions including reparations and monetary contributions to Indigenous groups of the territories I’m living on.

As fascinating as it is to explore what was published in your latest book, there’s often something to discover from what’s edited out of the final draft. While editing your memoir, an inherently personal project, were there any ingredients you found especially difficult to leave on the cutting room floor?

My publisher and editor were so helpful in this regard. They really saw my vision for the collection and were able to help crystalize all of these variegated pieces on masculinity, gender, embodiment, and class, and help me to wrangle them into something that flowed and drew its own internal narrative arc. There was a really lovely back and forth process, one in which I had so much agency and say, and one that was really beautiful and graceful, too. So, there were many things left out, and I really don’t miss them, and a couple of pieces that we went back and forth on, and now all of that work has taken on a new life in this current iteration. The sense of proximity and adjacency of the essays as structured in the book, to me, now give them a different read as a whole beyond how they seemed to function as solo essays in lit journals or anthologies, and that’s super exciting to me.

Your history as an essayist is nothing short of incredible. You’ve appeared many times in empowering queer magazines, such as Original Plumbing. You’ve contributed to educational anthologies, such as The Remedy: Queer and Trans Voices on Health and Health Care. You’re definitely no stranger to the world of publishing. What’s your greatest asset as a prolific writer? How would you advise emerging writers to nourish their own skills as they ready themselves for publishing?

I definitely do not see myself as a prolific writer. I see myself as a writer who very much embodies my astrological sun sign as a Taurus: my work is slow and steady. I pull the plow. I also take a long time to conceive of something as “ready.” This cuts both ways, however, because I’ll take stock and realize that I have another book’s worth of material just sitting there in folders on my computer, and the whole point for me of writing is to be in conversation. I’m not writing to have all of my creations found in shoe boxes under the bed when I die. I’m writing to engage.

The biggest piece of advice I can give would be to develop a practice, consistently make work, and engage that work with audience through readings, workshops, et cetera. Focus more on the making of art than the outcome. Let process be as important to you as publishing. And, read as much as you possibly can.