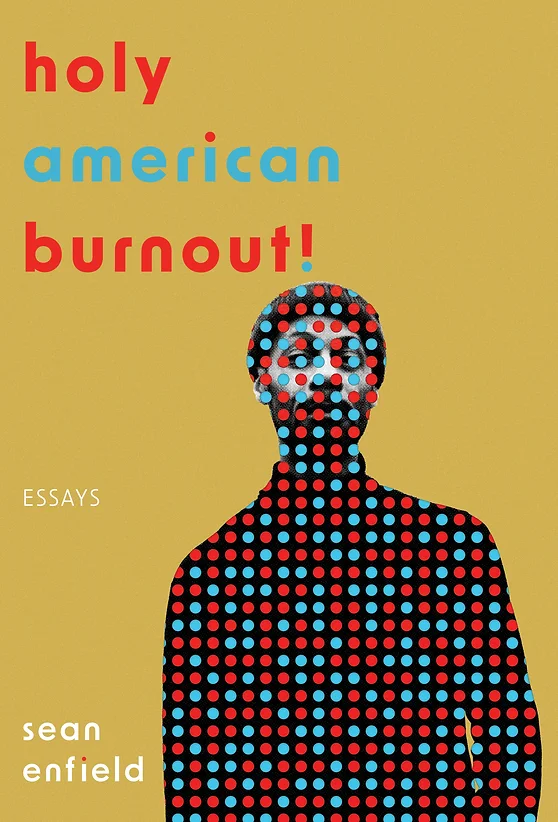

Balancing personal truths against the raw realities of American society can seem impossible in today’s political climate, where ideas about truth and justice often feel up for debate, and an issue’s relevancy seems determined by the number of likes it receives on Instagram. Yet debut author Sean Enfield, in his wildly experimental and poignant essay collection Holy American Burnout!, released in December 2023 by Split/Lip Press, invites us into a conversation that successfully navigates this fine balance.

The framework for Enfield’s collection stems from a school year spent teaching at an all-boys Muslim middle school in the suburbs of Dallas. The author, a first-time teacher, finds himself faced with a classroom of surly pubescents, and he struggles to balance relevant curriculum with the realities of the classroom. He wonders: how do we access students when the systems and pedagogies that exist to help teachers don’t address actual student needs? To answer this, Enfield looks inward—at himself as a Black man, at his own experience in educational systems, and to his passions for music and language.

The interplay between personal and political appears in the first essay and never lets up. In “To Pimp a Mockingbird”, the author manipulates the structural form of a lesson plan to draw connections between Kendrick Lamar and Harper Lee. This upending works beautifully—suddenly the academic canon rings hollow, the white-savior narrative gets laid bare, and we discover that, “maybe it is just best to hold all stories—literature, hip-hop, or otherwise—side-by-side for what they might say about each other and about ourselves” (11).

Enfield employs music criticism, his own body, and even social media structure as literary devices to make this collection feel both insightful and transcendent. We laugh even as we’re forced to contemplate how censorship, racial prejudices, and the misguided priorities of systemic education make meaningful social justice reform in the classroom feel impossible.

Early essays move through an array of camera angles to address the need for honest and useful dialogue about current societal problems. In “Call me Coach,” for example, Enfield becomes the basketball coach, despite having no experience with the sport. He considers the way his skin color becomes stereotype, and how Black men in education always seem to be either absent or coaches.

“Teacher, Don’t Teach me Nonsense” holds up a mirror to progressive educational theories and demands we ask whether such radical ideas can actually work within a broken and racist society. “I want so badly to do better,” writes Enfield, “to be…a decolonizing guide in this colonial system. Doing better, however, is rooted in the body and this body comes home so tired that it time travels through sleep” (36).

As the collection progresses, we feel Enfield’s exhaustion with him, that titular burnout growing from the unrelenting pressure of implicit racism, hours-long commutes, broken cars, failed lesson plans, and the fear that his efforts aren’t making any difference. The exhaustion is marked by an experimental style shift—across the second half of the book, Enfield places colonizer titles and place names in lowercase. His effort to bridge the political and the artistic makes the systemic inequity all the more palpable, a flourish that reminds us how, for Black folks, “a lower-case america looks like our america” (author’s note).

Enfield often uses footnotes to provide context and, presumably, to poke fun at traditional academic form. These asides range from website links to full citations to personal commentary (“who among us hasn’t mistaken a TGI Fridays for a Chili’s?” [15]). Like most of his experimentation with language and form, the footnotes mostly work, adding poignancy, depth, and humor, and they give us a break from the immediacy that holds us in the main narrative’s sway.

Yet it isn’t only the artistic play that gives this collection such depth. Its greatest strength resides in the way we feel the world outside the classroom seep into the increasingly exhausted psyche of the author. For Enfield, daily life and an awareness of history combine to form an inescapably personal reminder of the growing chasms in our society.

In what may be the best essay of the collection, Enfield’s white, conservative grandmother shares a bootleg copy of Disney’s “Song of the South” with her mixed-race grandchildren. The hidden history of a racist pop cultural artifact serves as a platform for understanding the complicated relationship between racist hate and familial love. And this memory forms a connective tissue binding the author to his Muslim students amid a presidential campaign that celebrates white supremacy. Over and over, Enfield lays bare the disconnect between the narratives we tell and the hard truths those narratives obscure.

Whether talking about music, suburban landscape, or the way subjugation begets the ever more insidious subjugation of non-white bodies, Enfield reminds us how intertwined the seemingly disparate parts of our society actually are, threads “connected not by the land itself but by the many intersecting highways snaking through it” (121). He reminds us we can’t extract the parts from the whole, and that we should beware, for the sum total of our current division is threatening to crush us.

Ultimately, Holy American Burnout! offers a beautiful exploration of the social landscapes we inhabit and a poignant reflection on the responsibility we have to those spaces. We realize that the work is endless and the institutions are broken, but these essays also give us hope. “Still, we can hold each other up,” we read. “We are never as alone as we think” (155).

Faced with the exhaustion of teaching, the relentless strain of inequity, and the institutional attacks, it is still possible to re-envision the narrative. When grappling with collective burnout, we fight back against power in the only way we can—by sharing our pain.

Enfield, Sean. Holy American Burnout!: Essays. Split/Lip Press. December 2023. 178 pages. $16.00