Piebold, Maryellen. “Work By 15th-century Female Artist Discovered

Moldering in Monastery Basement.” The Adventurous Traveler. Retrieved

online: 3 May, 2019.

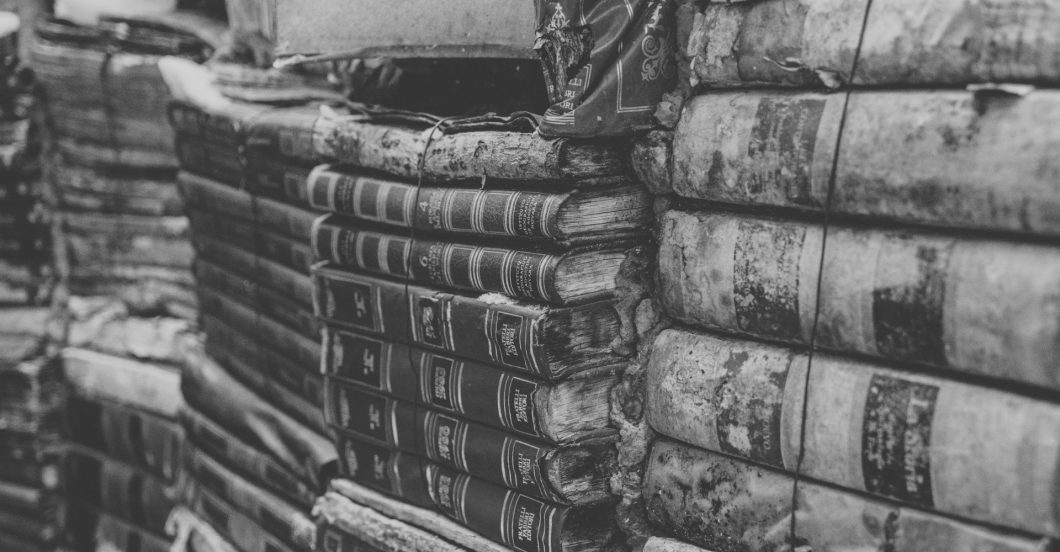

The books on the shelves of the San Francesco sopr’Arno monastery

in the Tuscan village of Sieci were almost entirely damaged by a burst

water pipe in 2010 that went undetected for nearly two years. The flood

ruined an estimated two hundred rare manuscripts and texts, but the

monastery, which reopened to the public as a museum just last week, still

managed to make a remarkable discovery: along with the restored maps of

sixteenth-century farmland in Tuscany, San Francesco sopr’Arno

monastery displayed a partially-destroyed and very rare incunabulum—a

book printed before the 16th century—created by a woman.

“We were stunned and very excited by the discovery of this early

female artist,” said Antonio Giorgi, the Milan-based investor who, just last

year, financed the recovery and restoration of the monastery and its

grievously neglected library. “Joan di Paolo should be a well-known artist,

but her work has until this point been developing mold in our basement.

We are relieved that her name—and her remarkable prints, though

damaged—will finally see the light of day.”

Di Paolo’s work will be on display for the remainder of the year at

San Francesco sopr’Arno. Ticket reservations can be made on the

museum’s website.

**

“Joan? Are you in there?” Eleanor’s voice echoes oddly in the basement stairway. “Yes,” I say. “Just reading the news.”

I close the article about Joan di Paolo as Eleanor makes her way down the stairs. “Why are you tucked away down here?”

“I like it down here,” I say, waving my hand around at the piles of things my mother has hoarded over the past forty years—tennis rackets, tea cups, a child’s battered desk. Most of the clutter accumulated in the years she was married to Eleanor’s father.

Eleanor shrugs and pulls up a chair. There’s sweat on her forehead, and she smells of ink. “I came down to ask about my biographical note,” she says. “The text for my exhibition catalog is due at the end of the week.”

“I’m editing it.”

“You might want to mention my summers at Camp Sunrise. That had a profound impact on my early artistic development. It’s where I first encountered the kiln.”

“Right,” I say, sliding my notebook from a stack of papers and taking distracted notes.

“And don’t forget my stint at Black Forest. Exhibitions tend to leave that residency out.”

I pick at the corner of my lips, an old habit. My eczema always comes back when I’m home. Eleanor reaches across the desk and pulls my hand away. Eleanor is older by two years, but now that we’re both in our sixties, I resent her mothering.

“Where’s Rachel?” I ask.

“In the bath.” As Eleanor says it, we hear a thump upstairs.

I make it up the stairs first to find my mother on the bathroom floor, naked and blinking up at me. My heart is in my throat. I move to help her sit up, but then think better of it. Should I try not to move her neck? I grab a towel and drape it over her, then feel delicately around the back of her head. Her thin neck hairs tickle my fingers. I don’t feel any blood.

Eleanor enters the bathroom, huffing slightly.

“Should we call an ambulance?” I ask, my voice higher than usual.

Eleanor sits on the edge of the bathtub and hoists Rachel up by her armpits. When I make a motion to stop her, Eleanor says, “She’s fine.”

“I think we should take her in, just to be sure,” I say. My knees are starting to ache from kneeling on the bathroom tile.

“Not much they could do for her. If she’s concussed, they’ll just recommend rest.”

“But what if there’s internal bleeding?”

Eleanor takes my mother’s hands and helps her to her feet, then wraps a bathrobe around her. They take a few tentative steps, Mother hanging onto Eleanor’s arm, and then they stumble. I lunge for them, setting both off-balance. Eleanor slips and lands on her backside, letting out a cry of pain. Her body prevents Rachel’s from hitting the tile again, thank God. I’m horrified at what I’ve done and apologizing madly as I try to help my mother stand again.

“You’re making a mess of things,” says Eleanor from the floor.

I can’t muster a response. Eventually, we manage to settle Rachel into her bed, and after I retrieve an ice pack for Eleanor and a warm eye mask to soothe my mother to sleep, Eleanor says, “I can manage all this without you.”

“I came back to help,” I say.

Eleanor gives me a wary look. “You’re running from something, aren’t you?” I bring my hand to my lips again and pick at the edges.

“I’m no stranger to caring for sick loved ones,” says Eleanor. “But you would avoid it like the plague, unless there was something you were hiding from.”

A rock lands in my stomach. Eleanor raises her eyebrows and then walks away, holding the ice pack to her backside and leaving me to my thoughts.

**

Biographical Note

Eleanor Gould Roseburg was born on March 15,1953 in Cleveland, Ohio.

The prolific artist is best known for her woodblock prints of urban life and her

lively pen-and-ink sketches of domestic scenes. Her art is heavily influenced by

Mary Cassatt and Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as her life in Cleveland.

Roseburg attended Rutherford High School (1967-1971), where she met

her future husband, Joseph Roseburg. She began drawing at a young age, and

credits her summers at Camp Sunrise with an early introduction to ceramic arts.

Roseburg attended Cleveland State University for one semester (1971) before

transferring to the Pratt Institute (1971-1972) in New York City, where she

studied under Heinreich Honecker, the East German émigré famous for his

etchings of Communist Berlin. Eleanor left Pratt after one year to care for her

dying sister. She then spent one semester at Oberlin College (1974) studying

sculpture before leaving school for good. Around this time, she began to exhibit

her early drawings and watercolors at Rogerstein, a Cleveland art gallery, catching

the attention of the director of the Isherwood Colony in North Carolina, an artist

residency program.

She married Joseph Roseburg in 1975 and attended residencies at Black

Forest (1982), Wisconsin University (1985) and Virginia Colony for the Arts

(1990). In 1987, Roseburg acquired a permanent gallery in Cleveland, which is

still the primary sales point for her work. She divorced her husband in 1990, the

same year she opened a second gallery in Shaker Heights. In 2019, Cleveland

State University put together a retrospective of Roseburg’s work, for which this

exhibition catalog serves as a guide.

**

I save the biographical note and check my email. There’s a new message from Nicolas, sent in the middle of the night—morning in Amsterdam:

Joan —

Have you seen this?

I click the link that follows and swipe through a series of Instagram posts from a printmaker in France. Using Google Translate and my own high school French, I’m able to decipher the post, which is accompanied by reasonably-good screen prints of a woman in a deluge of rain. In my mind, I catalog the discovery:

Lambert, Agnes [@lamertartiste34]. “New prints.” Instagram, five

images. Retrieved online: 3 May, 2019.

The beauty of the elements in full color—terrifying but transcendent

in the capable hands of Joan di Paolo. My new series is dedicated to

her. Take that, da Vinci!

A bubble of terror roils inside me. I click back to Nicolas’s email.

When we said goodbye in Sieci, I advised you not to move forward with

your idea. I see that you have done so, and now I counsel you to “come

clean.”

Even in my terrified state, I take some pleasure in his quotation marks, which he uses liberally whenever he employs an American phrase. I always read his emails in his clipped Dutch accent, which makes me miss him more.

We are professionals, Joan. You had a “lapse in judgment” and you should

reveal your mistake now. The dignity of our field is at stake. I do not think

you would be ruined if you admitted to the forgery now, before this gets

“out of hand.” I fear that it will become a “shit show” if you stay silent.

I hope your mother is well. I do miss you. My work with the Kleinfeld

archive keeps me busy. I will call you soon.

Nicolas

**

Water is the strongest force in my life. I’m a disaster cataloger by trade—not a cataloger of disaster, but the cataloger called in to go through the wreckage of a library after a disaster. Since I was in my twenties, I have followed tsunamis, hurricanes and floods around the world. I know the various methods for drying wet books: the benefits of sawdust, which types of paper have to be lay flat to dry, how to use freezers to delay the development of mold, the drawbacks of hair dryers, the importance of submerging microfiche in cold water after it has been soaked by flood, and so on. I arrive at the scene of devastation as everyone is trying to get out, assess the damage, triage manuscripts, keep track of which treatment has to be applied to which books, and then supervise the reorganization of the library once as many texts as possible have been saved.

But the Sieci assignment was unlike any other I’d accepted. My task was to recreate a ruined catalog, and would be used to restock the San Francesco sopr’Arno’s library with facsimiles of the texts that had once been on its shelves.

“The bulk of the research will come from the letters,” Antonio Giorgi had said when he offered me the job. “As for the rest, I don’t know. Guess.”

I agreed to work on the catalog, but privately vowed to stick to the facts. I told myself I would rely on the boxes of correspondence between the monks, their book sellers, and visiting academics—to re-create the catalog. I requested that Nicolas Heller, a medieval art specialist from the Netherlands, be called in to consult on the maps. I have limited experience with map cataloging, and besides, Nicolas was my lover. We met in Amsterdam a decade earlier while working on the recovery of a flooded university library. If I could convince someone to pay him to come to Sieci and work with me—well, so much the better.

“Four months,” said Nicolas, when he arrived in Sieci to inspect the extent of the water damage at the library. “Tell Giorgi we can do it in four months.”

The next few months were bliss—there is no other way to describe it. Nicolas and I spent every day together in the ruined library, albeit wearing construction-grade masks to ensure we didn’t breathe in too many lethal mold spores. We worked in silence, or while listening to Chopin or Debussy on Nicolas’s Bluetooth speakers. I could talk to Nicolas about anything. He knew about my strained relationship with Eleanor and my mother, and I knew about his son, who worked as an architect in Paris, and his ex-wife, with whom he was on good terms. But mostly, we talked about our work. Nicolas, soft-spoken, scholarly and meticulous, is the perfect cataloger.

“We’re at our best when we are invisible,” he said in the middle of a Nocturne one day. “We describe the item in such a way that the viewer happens upon the work as if she is the first person to see it. We create the illusion of discovery.”

“But in reality, we are the ones who discover,” I said. Chopin’s wandering trills filled the silence.

“Yes,” Nicolas allowed. “But it is not about us.”

We disagreed about the position of the cataloger. I said that our names should be included alongside our work.

“In the exhibition catalog,” I clarified, “not with each entry.”

“What would be the point of that?”

“Recognition. Acknowledgement of the time and skill it took to analyze, interpret, and categorize.”

Nicolas pressed me on this. Why did I need the attention? Wasn’t the pleasure of my work enough?

I said it had to do with being Eleanor Roseburg’s stepsister. We have always been in competition with our work, bringing home prizes and jostling for attention from our parents. But an artist is intrinsically part of her art, whereas the cataloger always stands at a distance.

“Yes,” said Nicolas. “That is as it should be. The catalog should speak for itself.”

**

Eleanor Gould Roseburg (1953 – )

Girl Blowing Matches, 1974-5. Drypoint and aquatint on laid paper: 20 in x 30 in.

Cleveland, Ohio.

Reproduced here are three of Roseburg’s Girl Blowing Matches series.

They are, from top left and moving clockwise: Girl with Matchsticks, Girl with

Dandelion, and Girl with Balloon. They are from a series of sixteen prints that

Roseburg completed shortly after she left Pratt to return home and care for her

younger sister, Elizabeth Gould, who died in 1973 from complications related to

Childhood Interstitial Lung Disease. Roseburg’s matchstick motif is inspired by a

common test to establish a patient’s lung capacity: whether or not a patient could

blow out a match. Elizabeth, only twelve when she died, was a sweet child. She

and Eleanor were very close, especially after the death of their mother. Elizabeth

charmed her stepsister, too. Her death was a profound loss for the family.

Remarkable in these three prints is the whimsy with which Roseburg has

approached her subject. The light yellows and pinks created from watercolor

pressed onto the image give the resulting prints a sense of fleeting childhood.

However, when viewed as a series, the prints take on a melancholy tone; the girl

seems to age from one print to the next, and yet her task is always the same and

her expression one of resigned determination rather than childhood pleasure.

**

At the end of the four months in Sieci, I was nearly finished cataloging the printed materials. But I remained stumped by one last title: a sopping wet incunabulum. Bright orange mold blossomed from the center of every page. Most pages were so water-damaged that they could not be separated from each other, while others were half-disintegrated.

On my final day in the library, I stayed late to work on the incunabulum. I turned to the page that tormented me. It was a hand-colored print, but the ink had run and dark mold obscured the top half of the page. There were definitely animals on the page—bodies with four legs and two—and there was a lot of blue, suggesting an outdoor scene, or creatures in an ocean. Was it a biblical text? Scientific? One of the four-legged creatures looked like a dragon, but it could easily have been a bird.

There were a handful of letters between fifteenth-century monks about the incunabulum, but frustratingly little information about the content or provenance of the book itself. The letters referred to it once by its title, which translated to A complete guide to the hidden lives of animals and weather, as documented by diviners and peoples who have lived among the elements. A puzzling title on its own, but not totally unique for its time. In another sentence, though, a monk referred to the printer of the incunabulum as “she.” I didn’t know of any printers before 1500 who were women. Was it a slip-up? Or was I really looking at the only known incunabulum printed by a woman?

I ran my gloved fingers over the page and wrinkled my nose. My mask was starting to chafe at my cheeks and behind my ears. I blinked, looked up at the clock, and decided to call it a night.

Outside, I pulled up my hood against the deluge of water from the sky. Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink. The line was from a poem, or something. It often floated into my consciousness on nights like this, when my whole life and livelihood seemed sopping wet.

I got the call from Eleanor as soon as I was back in my hotel room and connected to WiFi.

“Rachel had a stroke,” said Eleanor, when I picked up the call. “She’s at Cleveland General.”

“Oh God,” I said. “Is she all right?”

But Eleanor’s face had frozen comically, with her mouth open and her head tilted back so I could see her nostrils. She seemed to be sitting in a waiting room. An exit sign glowed red over her left shoulder.

“Eleanor? Can you hear me?”

“Yes,” said the still-frozen face.

“What’s happened to mother?”

“Last night we were eating dinner and half her face went slack. I called an ambulance. The doctors are saying the damage from the stroke has been extensive. She’ll have trouble walking and speaking for a while, maybe the rest of her life.”

Eleanor’s face was too strange in its frozen state, and I had to close my eyes. I put my head in my palm, holding my phone aloft with my other hand.

“She’s going to need around-the-clock care,” said Eleanor.

“I’ll come home,” I said. I looked at the phone again. Eleanor’s image had unfrozen and frozen again just as she turned her head. Her face was now a blur.

“Don’t do that,” Eleanor said. “You have your career.”

“So do you. And I can’t afford a full-time nurse. Can you?”

“No,” said Eleanor. “But don’t come running back for this.”

“She’s my mother, Eleanor.”

“You haven’t come back for anything else.”

I let the silence lengthen. Eleanor was still frozen, and I hoped my video was, too. “I’ll talk to you tomorrow,” I said, finally. “I’ve got to wrap up a few things here before I can leave.”

I hung up and stared at my phone’s home screen. It was a picture of an illuminated manuscript, one that I had cataloged in Spain five years before. A woman was bent over a flower, pouring water from a bucket. The blue of the water was halfway to the earth, but the woman was looking up at the sky—hoping for rain or dreading it? The phone went black. I closed my eyes and saw my incunabulum. I would have to make a decision about it, and soon.

Guess, said Giorgi’s voice in my head. I needed to talk to Nicolas. I left my own room and went down the hallway. When I knocked on his door, I heard rustling, then the click of a lock. Nicolas’s face appeared in the crack, partially obscured by the door: his big nose, Delft blue eyes, the furrow of concentration on his forehead. He softened when he saw it was me and opened the door wider.

“I have to go to Ohio,” I said. “My mother is dying.” I was aware how dramatic it sounded, but I was too tired to compose my news any differently.

“Tell me,” he said, walking me to a chair.

“Eleanor says she had a stroke. She’s going to need full-time care from now on.”

“The catalog is nearly complete, no?”

“Just one text left.”

“I can finish.”

“It’s just the incunabulum. Nicolas, I think it was printed by a woman.”

“This conclusion—you have reached it from the one pronoun in the letters?”

“Yes, but also the art, the parts I can see—it’s more alive.”

“And that means it was created by a woman?”

“Well, yes. Nicolas, I think my career is done after this.”

“Nonsense.”

“Eleanor can’t be left to care for my mother on her own. She would lord it over me for the rest of my life. And I can’t have that. I have to take care of my own mother.” I was surprised to find my voice choked with emotion. “And I haven’t done what I meant to with my work.”

“You’re a world-renowned cataloger,” said Nicolas. “You’re an expert in your field.”

“Yes, but what new discovery have I added to our knowledge of the past?”

“It’s not for us to discover.”

“But—”

“This is about the incunabulum? You think it is a unique text?”

His eyebrows were raised, cautioning me to think before I spoke.

“I think it is monumental,” I said.

Nicolas drew in a slow breath. “You’ve had a shock,” he said. “Don’t make any rash decisions tonight. Do you have a plane ticket?”

I surrendered to his rational mind and allowed him to purchase a ticket to Cleveland leaving the next day. Nicolas’s mind worked as a cataloger’s should; he sorted and arranged, created systems and hierarchies. His job was to help others find the truth, not to create when truth couldn’t be established. His was not a flashy mind, but it was solid, practical and generous.

I closed my eyes and listened to the printer spitting out my boarding pass. I thought of the talk at the Swiss Institute for Library Sciences the following month. I would have to miss it.

If a library were burning and you had the opportunity to save one book, don’t choose the oldest or rarest. Choose the catalog.

That was how I started all my talks.

The catalog is the only document created by the library itself, and the only document that can re-create the library in its absence.

Here, I would pause and look around at the young faces, some of which might be looking back at me. More often, my audience would be clicking through tabs on their computers or apps on their phones.

The catalog is a best friend, I would say, capturing the attention of a few more distracted students. The catalog is unassuming and omniscient. The catalog is the one source of truth.

“Joan?” Nicolas was standing in front of me with my documents still warm and smelling of cheap ink. I blinked at him and listened, almost without comprehending, as he recommended what route to take to the airport the following day, and offered to mail me whatever I could not pack.

I stood and kissed him. His mouth tasted of toothpaste and something earthly, like mushrooms or sourdough bread. He put the documents safely on his nightstand before putting his hands on my body. In my mind, I arranged my last catalog entry. It blossomed out of nowhere, bursting into existence like the startling appearance of mold.

Joan di Paolo (1441-1495).

A complete guide to the hidden lives of animals and weather, as documented by

diviners and peoples who have lived among the elements. Sieci: Joan di Paolo, for

San Francesco sopr’Arno. 23 Dec. 1493.

Woodcuts: Images of flood, fire, and storm. Woodcuts of animals, and the

composition of heavenly spheres.

Decoration: Printed initials. Marginal notations in brown ink throughout.

Provenance: Inscription on title page effaced. – Library stamp, illegible. – San

Francesco sopr’Arno Monastery.

Notes: Mold obscuring 96 of 112 leaves. Approx. 80 percent merged

from water damage, impossible to separate; several leaves at front and

rear torn, staining throughout. Correspondence about the text in

question indicate volume was created by a woman artist or scientist,

with careful notes about the timing and progression of storms,

floods, and animal reactions to changing climates, though text of

the primary source has been mostly lost to water damage.

**

It turns out that my mother does not have internal bleeding from the bathroom fall. As I clean up after breakfast the following morning, Mother shuffles in and starts putting away the silverware, matching forks with forks and spoons with spoons and so on until the job is done.

“Shall we read in the living room?” I ask when she’s done.

Mother nods. I settle her on the couch with a newspaper and sit next to her, then open my laptop and log onto Instagram. I have a notification: a fairly well-known poet (judging by her number of followers) has tagged me in a post.

“New ekphrasis,” the poet wrote, “based on Joan di Paolo’s work. Gratitude to @disastercataloger for the discovery!”

The images in the post are screen-shots of the poem. I swipe through and skim the text. Not a fantastic poem, but reading it stirs an emotion in me. Excitement? Fear? There is undeniably something thrilling about reading my creation fictionalized in this way. As if Joan di Paolo roared to life when I wasn’t looking. Took her first breath all on her own.

But how had the famous poet found my Instagram? I had not, in the end, added my own name to the catalog I placed in Giorgi’s mailbox on my last day in Sieci. Perhaps the poet had done her own sleuthing? She might have seen the few posts I’d made while in Tuscany—my post about a Plutarch incunabulum I’d uncovered at San Francesco sopr’Arno certainly tied me to the monastery’s library.

My phone buzzes and Nicolas’s name flashes across the screen. I answer and my mother looks up, startled to find another person in the room.

“Someone’s written a poem about Joan di Paolo,” I confess before he can speak.

“Have you decided what you’ll do?” Nicolas asks.

I watch my mother’s eyes slowly blink closed. She falls into a doze.

“No,” I say.

“It’s only a matter of time before someone checks your work. You’ll be found out eventually.”

“Not necessarily. It’s a lot of work to fact-check a catalog. And anyway, people want a woman printer.”

“This is not about making people happy.”

“Will you turn me in?”

“Don’t make me choose—”

He is interrupted by the beep of an incoming call. An unknown number with an area code in New York. Without thinking, I hang up on Nicolas and answer the other call.

“Is this Joan Cohen?” a woman asks.

“Yes. May I ask who’s calling?”

“Cynthia Stewart, from Art Today. I’m calling to ask about the di Paolo incunabulum.” It feels as if the air has been knocked out of me.

“For a story,” Cynthia clarifies.

“Now’s not a good time,” I say. “I’m sorry, I’ll have to call you back.”

I hang up, my heart beating fast.

“Who was that?” Eleanor asks. I hadn’t noticed her come into the room.

“A journalist,” I say.

Eleanor raises her eyebrows.

“She wants to talk to me about a rare book I cataloged in Tuscany.”

“And you hung up on her?”

“Yes.”

And, perhaps because I am tired and confused and feel I have already lost Nicolas, my only friend in the world, I find myself explaining Joan di Paolo to Eleanor. By the time I finish my story, Mother is awake again, looking more alert than she has in a while. Both she and Eleanor fix me with the same intense stare.

“I don’t know what to do,” I say. “Tell the truth and ruin my career—or stay silent and lose Nicolas. And destroy the ‘dignity of the cataloging profession,’ according to him.”

Eleanor looks around the room and I am reminded of Elizabeth’s Shiva, which was held in that very living room. I came back from college for the funeral. Eleanor had been home for a year. We were all wracked with grief. But what I remember most clearly from that awful night is Eleanor, twenty and bold-featured, her eyes roving the room as if she already had everyone categorized, pinned and labeled. Her gaze was sharp and intentional, and I knew then that she would return to the scene later, her drawing tools in hand. She would put us all down on paper one day, in any manner she saw fit. It was the moment I realized Eleanor would be a formidable artist.

“What would you do, Eleanor?” I ask now, sitting on the same couch.

Eleanor opens her hands, palms facing upward.

“The world has another female artist,” she says, finally. “What’s so bad about that?”

My phone rings again. It’s Nicolas calling back. Eleanor leaves the room, taking Rachel with her. I let the call go to voicemail, listening instead to the sound of my mother and Eleanor talking in low tones, the squeak of Eleanor’s easel, the snap of her drawing box opening, and the wooden clatter of her charcoal pencils.

No, I cannot murder my creation, my crowning achievement.

I will let the catalog speak for itself.

**

Eleanor Gould Roseburg (1953 – )

The Cataloger, 2019. Color drypoint and aquatint on cream laid paper: 12 in x 23

in. Cleveland, Ohio.

The most recent piece to be added to Roseburg’s archive is this quiet

portrait of the artist’s stepsister at work. Roseburg completed the print shortly

after Joan Cohen (1955 – ) returned to Cleveland to help care for her mother (and

Roseburg’s step-mother) Rachel Cohen. In this portrait, Joan Cohen rests her head

on one hand and writes in a notebook, clearly deep in concentration. In contrast

with her serious, sharp expression, Roseburg chose a palette of soft

watercolors—creams, pinks, and browns—to render her stepsister, who also

happens to be the author of this exhibition catalog, at Roseburg’s request. The

romantic coloring and the blurred quality of the lines hint at the relationship

between artist and subject, and between the subject and her work— eliciting in the

viewer a sense of ambivalence and tension.

The author here notes the uncomfortable sensation of being the subject of

one’s own catalog entry. The circumstances surrounding this portrait are notable,

too, for they shed light on the contrasting impulses evident in this rendering: when

she sat for this portrait, Cohen had recently published a fabricated catalog entry for

a rare book in Tuscany. She falsely claimed that a female artist and scientist had

been the creator of an incunabulum documenting natural disasters in medieval

Italy. After the catalog’s publication, the imagined female artist, Joan di Paolo,

inspired several poems, art works, and scholarly articles before Cohen’s former

colleague on the monastery project, Nicolas Heller, urged fellow archivists to take

a second look at documents relating to the incunabulum. Upon closer inspection,

Joan di Paolo was revealed to be an invented identity, and Cohen’s work was

roundly discredited.

Cohen, in Cleveland with Roseburg when revelations about her falsehood

came to light, refused all interviews. Her honorary titles and awards from various

library science institutions were revoked. Cohen has decided to archive in this

catalog entry her only on-record statement regarding the scandal: “I do not regret

creating Joan di Paolo. I am only glad that she had a chance to live.”