I read an advanced copy of Ben Kline’s It Was Never Supposed to Be mere days after the 2024 presidential election was called. Meanwhile, pundits and journalists were stumbling over themselves to analyze results they found baffling, and I couldn’t help but feel that Kline’s work had already predicted its outcome. It Was Never Supposed to Be is a poetry collection, but it reads more like a contemporary history of queer life, and at various turns Kline punctures the illusion that the majority of Americans are growing more accepting of the LGBTQ+ community. His disillusionment with the average American is evident in one of the collection’s strongest poems, “The Legend of Swing Voters,” in which a speaker recounts a visit with his uncle who “chews the syllables of Obama like a schoolboy cussing.” When a cousin insists that the uncle’s backward thinking is out of style, and that liberals will ultimately triumph over conservatives in the next election, the speaker summons a cadre of “dead uncles”—or men who were left to die during the AIDS crisis—as proof of America’s longstanding indifference towards minorities. The poem clearly skewers conservatives who hate being called racist more than they hate racism itself, but it also chastises those liberals who want to believe that the majority of Americans are compassionate. As I read Kline’s work against an electoral map that bled red, and a flurry of articles arguing that Democrats should have sacrificed the rights of transgender people to secure more votes, I found his point of view refreshing.

If readers are worried that they will find Kline’s collection preachy or overly cynical, they shouldn’t be concerned. Instead, they will find his poetry shot through with defiance, sarcasm, and wit. If the essence of his collection had to be distilled into one sentence, it would be this: hope should always be tempered with reality, especially in political contexts. He captures, for instance, the optimistic view in the 1990s that the Clintons would recognize the LGBTQ+ community (and more importantly the AIDS crisis). In others, he confesses his admiration for Hilary Clinton’s “snarky responses which kissed the marrow in my gay bones.” But these poems are buffeted by others that highlight Bill Clinton’s cowardice and willingness to trade queer American lives to satisfy evangelical voters. Poems like “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” makes visible those that Clinton made invisible, the queer men who served in combat. Kline’s poem not only writes these men back into existence, it illuminates the multifold sacrifices they made. The speaker of this poem reworks the title of Clinton’s legislation, explaining that he never asked the servicemen he slept with to tell him about “their scars, phantom thumbs, the beard/they couldn’t grow,” and in turn they never shared these traumatic stories. This refusal to ask/tell doesn’t arise from not wanting to engage with despair, however. It comes from a profound love for these men whose mutilated hands run up the speaker’s thighs like “ivy insisting up the oldest oaks,” an image of resilience that stayed with me because of its quiet power.

While Kline’s poems speak to many historical figures and legislative acts, others broadly take aim at other hypocritical figures. Verging on the carnivalesque, Kline ridicules religious figures who publicly preach against homosexuality while privately cruising gay sites. An MFA mentor in “Gay Saints” insults a student he is having sex with by suggesting that his thesis is so stereotypically queer that even Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde would hate it. In “To the Closeted Republican Representative from,” the speaker lists the various sexual acts the two men enthusiastically shared and acknowledges that his poems often center on their relationship. Of course, all of these poems highlight power imbalances. Religious leaders influence votes against queer issues, even if they may be gay themselves, and Republican representatives pass laws that erode LGBTQ+ rights. Yet Kline assumes power over each of these categorial figures. I found the MFA mentor a sad cliché of the dirty professor who is also an elitist snob, and the religious figures that pepper Kline’s poetry to be fools. I was struck by the black bar that redacts the identifying state in “To the Closeted Republican Representative from,” because Kline protects the identity of this well-known man. The poem itself, which subversively takes the form of a sonnet, assumes a playful tone, as if he wants to thwart this leader’s traditional image. His real reason for calling him out doesn’t necessarily seem political, but rather mundane. The speaker is peeved by his Republican lover’s lingering insult and wants to hurt him for it. This is a poem that anyone might write if they were still angry about an ex-lover’s nasty comment.

The strongest, most original parts of It Was Never Meant to Be explicate the mundane, especially as it relates to queer men who lived under the constant threat of AIDS. Because Kline charts a wide-sweeping chronology from Reagan’s administration to the COVID pandemic, we witness the shift from men fearing the results of their HIV tests, to their legal marriages dissolving. Men meet for awkward dates in Applebee’s with those they met online. They start to see openly queer actors and celebrities on television shows and magazine covers. Kline depicts this slow normalization of queer culture best in his poem “Lover.” The experimental poem is presented as a lesson plan, one that allows the prospective couple to anticipate the trajectory of their entire relationship: they will fall into traditional relationship patterns while still trying to incorporate the risk they crave. In describing their relationship, Kline’s tone is both satirical and sincere. The couple will likely adopt a “butterscotch labradoodle named Riley,” take trips back home to families, and cook dinner for one another. But they will also have to discuss sleeping with other men and opening up their relationship. Risk is there, sort of, in the sense that it is literally written into the lesson plan’s objective, but I couldn’t help but feel that risk loses some of its appeal once it has to be planned. In other words, lovers explicitly incorporating risk in a prescriptive plan normalizes and potentially neuters it. The risk available to the couple in “Lovers” appears nothing like the risk that men took while cruising in the 1980s and ‘90s, a subject that Kline returns to many times throughout this collection, often with a nostalgic tone.

Ultimately, Kline wants us to consider what risk now means to a population that once faced death every time it was sexually intimate. After all, several of Kline’s speakers are bewildered that they are even alive. They know they have lived past something they shouldn’t, so they struggle to acclimate to the normalization of queer culture because they never thought they would survive long enough to see it. The poems that capture the shock and grief of living when so many others didn’t are harrowing, while others that present speakers struggling to show outward displays of affection are sobering. That said, as Kline shows in poems like “PDA,” the trauma that Americans inflict on the queer community never really ended, it just mutated into “anti-laws” that target people’s pronouns and rights. In other words, he wants readers to know that queer citizens are still very vulnerable today.

At the same time, Kline is aware that many Americans aren’t always moved by others’ suffering. Near the end of his collection, he writes about the COVID pandemic in a series of hauntingly tense poems. In “We’ve Come so Far to Go,” the speaker has a wound stitched up at the height of the outbreak by a physician’s assistant wearing an ill-fitting mask. She shrugs when he lists the celebrities who have died, and the speaker, having outlived the indifference towards those with AIDS, wonders what might finally motivate Americans to care for one another. Certainly, the casualties of COVID (which exceed a million deaths, let alone those left disabled) were substantial, yet we’ve been eager to move past the pandemic without much acknowledgment of these losses. Kline’s poems challenge us to feel grief in the face of this apathy.

So many of Kline’s poems ask us to wrestle with the ways that institutions, systems, and individuals leave whole groups of people behind. We live in an era in which queer stories are being challenged by bans and politicians. Kline’s poetry is a triumphant reminder, however, that queer life and love can never be erased. After all, as he observes in “When My Best Friend Recommends PrEP,” all those that survived the AIDS crisis also endured the “bodies untreated in dumpsters/the scorn of vague obituaries,” and the insistence by “sociologists, preachers and politicians” that homosexual men were/are inherently promiscuous and immoral. In the face of all this rejection, queer men continue to “bare the truth/dug from our roots.” It Was Never Supposed to Be bares the truth to readers that queer men don’t want the validation of those that oppress them. More importantly, Kline shows us that they know better than to ever expect it.

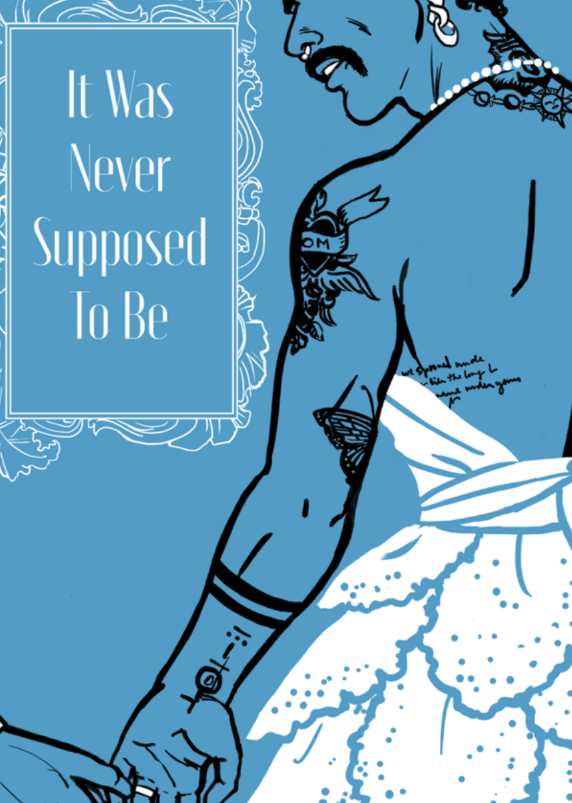

Kline, Ben. It Was Never Supposed to Be. Variant Lit. January 2025. 89 pages. $16.