Essie’s got hair like a dried dandelion. So blonde it’s almost gray, all scraggly thin and light looking. So short you can see right through to her scalp. Sitting in the desk behind her, I like to imagine I’m blowing on the top of her head. I pretend I’m watching the little pieces of hair scatter in a thousand different directions—hair floating up to the ceiling towards the missing tiles, the missing tiles I like to count. It’s a lot better than trying to focus on Chicken’s rambles.

Everybody calls our teacher Chicken because he’s got skinny little legs and he moves his head back and forth when he talks. He wears khaki shorts and tie-dye shirts. Plays us all these videos from Woodstock and the Civil Rights Movement. None of us mind, because we use the time to sleep or draw or daydream. Some people roll joints inside their desks for later, scratch tags on the tops of their folders.

Gloria Gonzales and Mary Rimichi paint their nails in class, even when we’re watching videos and it’s dark and hard to see. Gloria’s got at least ten different tubes of polish she carries around in her backpack, since they paint each fingernail a different color, not giving a care that the rest of us have to breathe it in. Gloria and Mary are best friends with matching overly plucked eyebrows. They hiss names over at Essie, call her things like “Bald Girl.” Yesterday, when they were calling her names, Chicken had a Jimi Hendrix video playing. Hendrix wore this bright blue scarf wrapped around his neck, and he was playing the guitar with his teeth. His jeans so tight all of us guys were laughing because you could see the outline of his nuts. Chicken said, “Hey, settle down, that’s how the cool guys wore their jeans back then.” And we kept on laughing until he pressed pause and asked if he needed to call security. “Naw, we’ll stop,” we said.

Essie spends only as much time at Culver Park as she has to. Doesn’t hang out in the bathroom after school messing with her face like most of the other girls. When Chicken lets us out, she takes off, walks as quickly as she can out the front entrance, past security and all the other girls strapping their babies in strollers from childcare next door, waiting for their boyfriends to remember what time they were supposed to pick them up. Sometimes if I’m quick enough I can make out the back of her dandelion head moving across the sunburnt lawn, past the cars bouncing heavy with bass. She always turns left on the sidewalk, then crosses the street and keeps on walking straight ahead. I don’t know where she lives. What I do know is that she’s smart enough not to stick around and wait for Gloria and Mary to start more shit. They’re just jealous of Essie anyways, even though her hair is practically non-existent, all of us guys still think she looks like that girl from the band No Doubt, with her black bra that bleeds through her white wife beater, her pout all lined in red and her big brown eyes, too big for her face. Essie’s new here and so am I. New isn’t something to celebrate. The guys around here don’t throw you a welcome party when you first get here. They make it hard on you. Even when you tell them you’re from nowhere, they strip your ass naked in the bathroom, search your body for tattoos that’ll tell them otherwise.

I first saw Essie a month ago, in September at Culver Park’s Open House Night for new students. Essie came with her dad, and I was with my mom. The rest of the room was scattered with tired parents just getting off work. It was strange looking out the windows of a classroom with the sun setting outside. I could see the family in the house across the street sitting down for dinner. Essie’s dad wore blue jeans and black motorcycle boots. My mom had gotten dressed up for the occasion—all done up in a suit jacket and skirt, even put on makeup.

My father didn’t come. He was too busy with the apartment property he’s just bought, and he told my mother when we were leaving that she shouldn’t waste her time talking to my new teacher. That I’d be eighteen soon anyway, and I didn’t need to graduate. I’d just manage the apartment property, live in one of the units like they’d been discussing for the last year, when I kept getting in trouble for smoking weed and ditching school, and my mother was freaking out wondering what the hell I was going to make of my life.

“He doesn’t have to be some sort of intellectual,” my father said, watching my mother apply her lipstick in the mirror above our fireplace.

My mother said, “What’s that supposed to mean?” She’s always thinking my dad’s talking bad about my grandfather—her father, who my dad thinks never really liked him because he’s just a construction worker and sells real estate from time to time on the side.

My grandfather had been a scholar in Russia. Last year, before he died, sick for the longest time in County Hospital, he made sure my mother collected his books out of storage. The books my father didn’t want to keep in our house. Now, my mother spends most of her nights baking bread and hovering over the kitchen table with a cup of tea reading them. Says she doesn’t want to forget her Russian. My father doesn’t speak Russian to her anymore and I barely remember it now. I was three when we came to Los Angeles. My father says, “Who needs Russian? They treated us like shit. That’s why we left. We were Jews, not Russians. Here, who cares? We’re Americans now.”

My mother held her handkerchief over her lips as Chicken explained our options at Culver Park. He told the parents we had to be here because most of us were asked to leave our high schools due to truancy, fighting, or gang violence. Some of us were on probation. Some of the girls were pregnant or already had children and needed access to the childcare facilities next door. Some of us wanted to earn our GED and then go on to community college. No matter why we’re here, Chicken said we had a choice to make. We had to decide how we wanted to spend our time. We could simply ride it out until we turned eighteen or create a study plan to help us get back on track and try to graduate. He was here to help motivate us to learn and believed in a variety of non-traditional teaching methods. “I’ve gotten almost a hundred kids to graduate,” he said, pacing back and forth behind his metal desk covered in books, mostly musician biographies and white conch seashells with pink insides. The kind where if you hold them up to your ear you can hear a noise. When I was little, my grandfather showed me how you could hear noise by putting an empty cup to your ear. I remember the glass slipped out of his shaky fingers when he was showing me how. My mother ran into the kitchen like a police officer, screaming. Shards of glass sprinkled across my bare toes. “Keep your hands up where I can see them. Don’t make a move, not one move,” she’d said.

Essie’s dad bit the inside of his lip watching Chicken talk, while she flipped through a Jim Morrison biography, and I—I didn’t know what the hell to do. Didn’t know what I wanted. I wondered if Essie had ditched school, too. Wondered what high school she had come from—if she’d just moved to L.A.

In the car driving home my mother told me I should think about the GED. I could enroll in a two-year program at Santa Monica College and then transfer to UCLA. She repeated my father’s idea: I could have one of the apartments when the property was fixed up. A nice place to study, explore different classes and figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I was her only child.

“The thing is,” I told her, throwing up my hands. “I don’t know what I want to do.”

“What do you mean you don’t know?” she said. “You have a lot of potential, Joseph. Just think hard about what you want to do, and it will come to you. It will.”

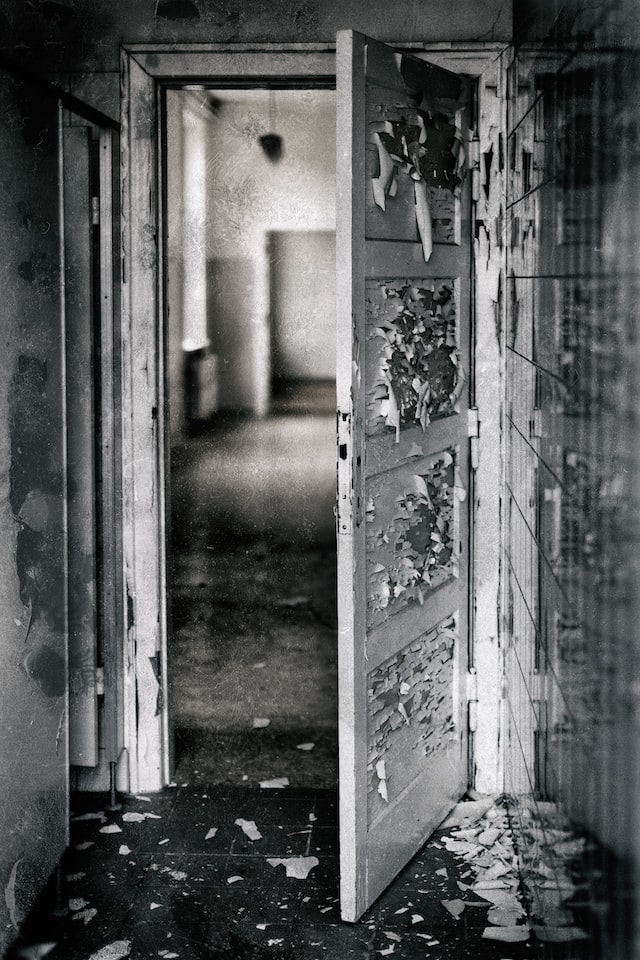

Later that night, I went with my father to check on the apartment building. He likes to make the rounds after dark, and I always go with him. He’s got this nervous habit of clicking his industrial flashlight off and on as we walk through the courtyard, around the empty pool and past the naked lady fountain, cracking and covered in moss. The naked lady keeps her right hand over her left breast, the other on her hip as if she’s tired of waiting for someone to dust her off, to turn her back on. My father bought the place abandoned. It’s only a few blocks from our own house and about a half a mile from Culver Park. An old Spanish style apartment building with flaking mint green stucco. Gold letters on the front that spell, The West Palm. It needs a ton of work before it’ll pass city code and inspections, before he can rent it out to tenants. My dad’s hiring a crew of workers next month to begin the renovations.

Sometimes we find people there. Squatters. Vagrants, my dad calls them. Each door is locked, but people manage to break through the windows. Once we found a woman in a tight, gold dress clutching a paper bag filled with empty soda cans in the bedroom of #2—a kitten rubbing itself against her bare legs. Another time, outside of #4, a man with duct-tape wrapped around his waist told my dad he was nursing a stab wound a friend of his had accidentally given him horsing around. He begged my dad not to call the cops. “I’ll be gone faster than a fly on shit,” he’d said. He had no teeth. Only a mouth full of grinning gums. A sky without stars, my grandfather used to call it, when his dentures would go missing.

“Do you like anyone?” my father asked when we reached #6, the last inspection for the night. “Of course, I’m sure you talk to girls. I mean they call the house sometimes. This I know,” he said. “Believe me. But, you know, have you found anyone special?”

I said no, surprised at the question. We’d never talked about girls before. He’d never given me a “sex talk” like other parents. But when he asked me this, I couldn’t help thinking of Essie at the Open House, sitting next to her dad in her beater and Ben Davis pants. That bright red lipstick and those gold hoops dangling off her ears. Of course, I didn’t know her name that night. I’d learn it the next day in Chicken’s class, and I hadn’t even seen her hair yet. She’d had her head covered in a black bandanna, like the way the woman in that 1950’s poster wears it, that Chicken’s got hanging up in our classroom. The one where she’s flexing her muscle and above her it reads, We Can Do It!

“Because if you do,” my father continued, clicking his flashlight on and off as we walked back to the car, “You should let her know. I don’t think I let your mother know enough,” he said.

When we got home, the house smelled of banana bread and my mother was sitting at the table pouring herself a cup of tea, my grandfather’s books scattered around her.

“Was everything okay, Samuel?” she asked.

“All clear tonight,” my father said, standing behind her. He looked down at my mother’s shoulders while she went back to reading, at the string of freshwater pearls he’d bought for her last birthday wrapped around her neck. I knew she smelled like lavender, and I knew he knew that, because that’s the kind of perfume she wears. My father stood behind her for some time, and my mother didn’t seem to notice. Or if she did, she pretended she didn’t. The last time I saw my father hold my mother was when my grandfather died. After they got back from the hospital my mother collapsed on the carpet and my father got down on the floor with her, while my mother sobbed and shook in his arms. My father did all the cooking and even baked the bread that week. The bread was lumpy and lopsided, and none of us ate any. Still he kept making it every night—that entire week, anyway.

**

Today, I get to Chicken’s class during video time. I overslept and shot out of bed to the sounds of clanging silverware. I’d found my mother in the kitchen, washing dishes.

“Why didn’t you wake me up?” I said.

“What does it matter,” she said. “That’s not a school you’re going to.”

I find my desk and sit down. I slouch real low in my seat as if I don’t care, but I can’t help watch what Chicken’s playing. It’s this documentary about an inventor named Leon Theremin. He created one of the first electronic instruments. It’s called a Theremin and you play the thing without touching it. You wave your hands over it to create the music. It sounds like the soundtracks for old movies or sometimes even like aliens talking. Leon came to New York from Russia in the 1920’s and played with the New York Philharmonic. He was a conductor for a whole electronic orchestra there. Chicken presses pause on the VCR and explains that without Leon we wouldn’t have Jimi Hendrix. When Leon went back to Russia, he was put into a sharashka—a Soviet labor camp—and later ended up working with the KGB for many years.

As I sit watching, I can’t get over the music he’s playing. The music sounds like shadows if they could talk, like the cry of a violin—my parents always wanted me to play the violin.

I cover my hands over my eyes as if I’m tired. Press down so hard, I start seeing kaleidoscope patterns that float around with the music.

And then I open my eyes because even with my hands covering them, it feels like someone’s watching me. It’s Essie. She’s turned her head over her shoulder and I can make out her face and the outline of her eyes. Chicken sits at his desk lost in the screen and I can hear Gloria and Mary whispering. Essie smiles at me, sticks her tongue out, and then turns around.

After Chicken tells us we’re dismissed for the day, Essie doesn’t rush out the door like she usually does. Instead, she walks up to Chicken and asks if she can speak with him for a moment. If she can show him something she’s written. I take my time putting my things back inside my backpack. The things I bring, but never use. Fresh lined paper in a folder I’ve never opened and two sharpened pencils I’ve never written a thing with. I head outside to find a place to stand on the lawn and wait for Essie. I want to talk to her. I want to ask her if I can walk her home.

The lawn’s crowded as usual. Guys stand around shooting the shit with cigarettes tucked behind their ears. Some of them take off their sweatshirts, posing in just their beaters, showing off their muscled arms. The sun at this time in the afternoon is wide and heavy. Gloria’s got her back pressed up against the trunk of a palm tree talking to Mary. They’re both laughing real loud and looking around, hoping some guy will notice.

I hung out with Gloria before she became friends with Mary, a few times back when we were both at the high school. This was when we were still doing the reading for our English class and we partnered up for a project on Charles Dickens. I went to her house to work on it after school and her mother was real nice. Gloria shared her room with her younger sister Lela, and they had all these animals. A turtle they’d gotten from Santee Alley, a blue iridescent looking Siamese fighting fish, and a white rat with red eyes named Blanca, nursing its babies. Her mother made us dinner and afterwards we took a walk around the block. I showed her some tricks with my skateboard and we talked for a couple hours in the church’s parking lot. Gloria told me she wanted to be a veterinarian, that she’d rescued baby squirrels before, fed them out of a bottle and took care of them until their eyes and ears opened and their tails puffed up, until they were big enough to climb trees. And that when she was a little girl she used to perform surgeries on insects. One time, she used a bit of clear nail polish on a broken moth’s wing and it was able to fly again.

Essie walks past me quickly, before I even have time to tap her on the shoulder. She walks past Gloria and Mary, and Gloria shouts, “Yeah, that’s right bald bitch, skip on home.”

“Why don’t you shut up?” I say to Gloria, running past her, trying to make it to Essie. I follow Essie as she turns left, and catch up to her when she crosses the street.

“Hey,” I say, grabbing onto the handle of her backpack.

“What?” she says, turning around. Her eyes are a lot lighter in the sun. I can see beads of flesh-colored makeup stuck to the peach fuzz above her lips.

“Don’t listen to them,” I say.

“I don’t,” she says.

Essie keeps walking and I keep walking right along with her. Two young girls ride past us on bicycles, long hair waving behind them. The street is shaded with trees. It’s the nicest block in the neighborhood. The windows have flower boxes and the grass is green. SUVs are parked in the driveways. My father once explained to me that these were real homeowners, and that he didn’t understand why such decent people would want to live near such a wretched excuse for a school; a school that’s just a jail.

I spot a sprinkler near the edge of a lawn up ahead, splashing the sidewalk, and slow down a little.

“You got a lighter, Joseph?” Essie asks, slowing down to match my pace.

“No. I don’t smoke,” I say, surprised that she’s said my name. That she even knew it. I like the way it sounds coming out of her mouth.

“Well, that’s too bad,” she says. “Because I was going to ask if you wanted to smoke a joint with me.”

“I smoke weed,” I say. “I thought you meant cigarettes.”

She stops and waits for the arch of the sprinkler to rise up to the sky, and shrugs. “No flame, no game,” she says.

“I think I can run in to that diner over there and grab us some matches.” I point at the diner across the intersection.

“That’d be sweet,” she says. “You should do that.”

She waits for me outside the diner. I hand her the matches. “Here you go,” I say.

“Nice,” she says. “Should we go to your house?”

“Can’t,” I say. “Mom’s home. What about yours?”

“Can’t,” she says. “Dad’s home.”

I look in the window of the diner, at a table filled with the remnants of a meal for two. A half eaten hamburger on one plate, a picked through salad on another, greasy crumpled napkins, a few scattered French fries. And just like that, this busboy comes by and in one full swoop makes it all invisible, pushing everything into his bin.

“I know where we can go,” I say.

**

We light the joint in the courtyard, both of us sitting on the rocky edge of the naked lady fountain.

“So, this is all going to be yours one day?” Essie asks, passing me the joint. She blows a puff of smoke in my direction.

“My dad’s going to let me be the manager, is all. I’ll get my own apartment.” I take a hit, hold it down as long as I can and then suck in another. I pass the joint back to Essie. Our fingers touch. From where we’re sitting I can look out over the courtyard, past the archway twisted with rusty colored jasmine and out into the street. A few cars rush by and seagulls squawk above us. The beat of their wings slap against the breeze.

“Well, you sure are one lucky guy.”

“Really? You think so?”

“Hells yeah,” she says, taking the last hit. “For sure. So much of life is figuring out how to make the rent. That’s why my dad and I move around tons. He loses his job and then we don’t make the bills. To have a place you know will be your definite home, that’s got to feel amazing,” she says, stubbing out the joint’s cherry on one of the stones between us.

“Where’d you even come from?” I ask.

“I don’t remember anymore,” she says, laughing. “I think I’ve almost lived everywhere. My dad says after I finish this year, we’ll probably head to Montreal. My aunt and uncle live there, they can get work for my dad. Cash. You know, under the table kind of gigs.” She leans in closer to me. I feel her arm brush against mine.

“God, I’m stoned. So freaking high that the paint on this place looks like mint ice cream,” she says, lifting her head towards the circling gulls. The skin on her neck is so white, I can see the veins swimming up towards her throat. I reach my arm up over her, touch the top of her head with my hand. Her hair feels a lot softer than I imagined.

“Is it still there?” she says.

“Your hair?” I ask, as if I don’t know what she’s talking about.

“I’ve been keeping it real short, practically buzzing it these days,” she says. “Should have started doing it years ago, instead of bleaching and dyeing it every single color in the rainbow. I damaged my hair permanently. It’ll only grow to my chin if I let it, and I look like a scarecrow when I do. Can you believe I used to have green hair? My head looked like a pile of seaweed.”

“I’m sorry,” I say.

“It’s okay,” she says. “You can touch it again, if you want to.” She leans over and places her head in my lap, curls the rest of her body in the fetal position and lies beside me.

I put my hand back on the top of her head and run my fingers through her tiny hairs. I can make out the lace on her black bra, soaking through her white beater. I try to stop my fingers from trembling against her scalp, and I’m feeling real thankful my pants aren’t all ass-tight like Jimi’s.

“You know, it’s funny how you were covering your eyes when you were listening to that music today in Chicken’s,” Essie says.

“Yeah,” I say.

“It reminded me of being a kid again,” she says. “You know, when you’ve cried and cried and cried, and you’ve got your face pressed down into the pillow and it gets so dark you start making out shapes and swirls?”

“I know what you mean.”

“We should try it.” She sits back up.

I close my eyes and press my eyelids down with the tips of my fingers.

“Wait,” she says. “I’ll hold your eyes down and you hold mine.”

“Okay.”

“Face me,” she says, patting the space between us. “Move in closer.”

I move in closer, our chests just a few inches away from each other. Her left bra strap dangles over her shoulder. We both reach across for each other’s eyes at the same time.

“Do you see any colors? Any shapes?” she asks.

I can barely feel her holding my eyes down and I don’t see anything at first, just feel my eyelids tremble and catch bits of outside light, but I don’t tell her this. The warmth from her fingertips feels good over my eyes. I keep my fingers over her eyes, hoping I’m not pushing down too hard. And then I imagine I’m watching Leon Theremin making music with empty hands, my grandfather and his laughter—the pink of his gums against the white of his fake teeth. My mother taking bread out of the oven. My parents hugging. My father’s flashlight clicking on and off. I see myself standing inside #6. It’s painted blue with white trim and it’s covered with plants that I’m watering. The plants have flowers as colorful as Jimi Hendrix’s scarves. I see Essie sitting on the sofa flipping through the pages of a book. She looks up at me and smiles. “You’ve got to read this,” she says, and holds the book out to me. It’s my grandfather’s. The title on the front is in Russian. I walk over to her and take the book out of her hands—and then I hear the wail of a siren in the distance, the wings of a helicopter slicing the sky.

“I should probably head out,” Essie says. “It’s getting late.”

But she doesn’t get up. She doesn’t take her fingers off my eyes, even though we both know we can’t sit like this much longer.

Image: Photo by Denny Muller, via Unsplash.