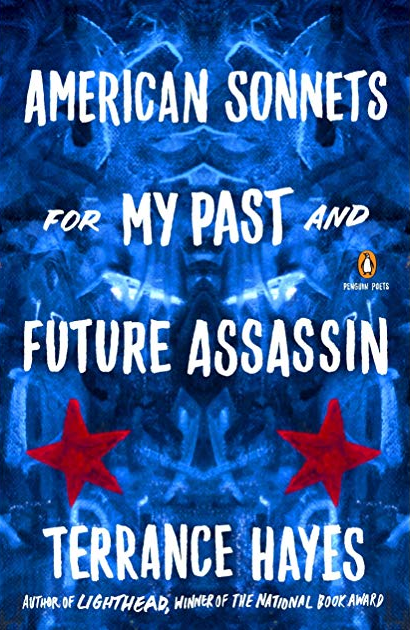

Re-reading American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes (Penguin Poets, 2018) at the end of 2018 was literally hard to stomach. I revisited the politically charged poetry collection on the day a seven-year-old child died while in U.S. Border Patrol custody and was reminded of the work’s visceral nature. Hayes’s keen focus on bodies creates a striking portrait of contemporary American life. The corporal anxiety of the collection mirrors the corporality of 2018, a year in which so many bodies were sacrificed. Through a poetics of touching inherent in the very structure of these linked sonnets, Hayes builds a sense of bodies stacked. Many of these bodies are ones we know—Maxine Waters, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, the Obama’s, Aretha Franklin. Countless others remain unnamed, haunting our consciousness.

In American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, Hayes sets a menacing tone:

I lock you in an American sonnet that is part prison,

Part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.

I lock you in a form that is part music box, part meat

Grinder to separate the song of the bird form the bone.

In a mere eighty-nine pages, Hayes uncoils social commentary that is as poignant as it is creative. He turns an attentive eye to the spectrum of inequities, from police brutality to white women internalizing the n-word through the gleeful consumption of rap music. Some lines blatantly point to the hypocrisy of America: “I carry money bearing / The face of my assassins” or “Something happens everywhere in this country / Every day. Someone is praying, someone is prey.” Hayes also takes on his characteristic interrogation of fathers and sons by tackling head-on the dysfunctional parent-child relationship America has experienced for the past two years: “Christianity is a religion built around a father / Who does not rescue his son. It is the story / Of a son whose father is a ghost.” Yet, he pushes the metaphor further, interrogating the role of the symbolic “son,” who is the American people:

America, you just wanted change is all, a return

To the kind of awe experienced after beholding a reign

Of gold. A leader whose metallic narcissism is a reflection

Of your own.

Hayes’s attention to positive and negative space illuminates the ethereal presence of ghosts in his poetry. In many instances Hayes’s ghosts are embodied, signaling the concrete realities of racial and generational trauma that live beyond one’s body in the new age. Hayes’s ghosts refuse to stay dead, an audacious afterlife that calls out the unlived lives of the living. In this way, Hayes speaks the dead back to life, for the reader to encounter in their own inactivity in the face of contemporary yet historical evils. Hayes’s is an implicating touch. Reading these poems bruises ones own accountability into being. Poetic velocity is weaponized into defiant agency, a reclamation through the written word.

Yet despite the breakneck pace of these poems’ dissent, there is tenderness, hope, and resiliency. Hayes delicately lays out a list of ten things the poet admires in the face of James Baldwin, or he imagines the heartbreak and invisibility of being Langston Hughes’s lover. He writes admiringly of the 20th Century’s most courageous leaders. Other poems are deeply entrenched in the intimacy of family romance: “Sometimes the father almost sees looking / At the son, how handsome he’d be if half / His own face was made of the woman he loved.” Shifting deftly between familial, domestic moments and calls for systemic change, Hayes’s work performs a ripple of possibility to inspire individual and collective action.

American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin halts the reader in the unsustainability of our contemporary social moment. It counts the bodies of the past in order to stop the accretion of future ghosts. The crux of the book comes at its closing:

I remember my sister’s last hurrah.

She joined all the black people I’m tired of losing,

All the dead from parts of Florida, Ferguson,

Brooklyn, Charleston, Cleveland, Chicago,

Baltimore, wherever the names alive are

Like the names in graves.

The collection reminds us of the connections between the dead and the living, and our roles in drawing these defining lines. At the end of two years of spectacular demonstrations of both civic engagement and inertia, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin reflects back the potential of human evils and accomplishments. Hayes reminds us that loss is nothing new in America, but our tolerance for it is waning. Aren’t you tired? he seems to be asking, an exhausted mourning that implores the reader for a kinder year to come.

—

Rosa Boshier is a Pushcart Prize nominated writer whose work can be found in publications such as Necessary Fiction, Entropy, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Acentos Review, and forthcoming in The Offing. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing at The California Institute of the Arts.