I decided to give the Museum of Palpable Art one last go before I gave it up as a bad job. The first two times had been busts, plain and simple. And when I had handed back my tangled EEG device to the docent after the first failed trip, beyond exasperated, she had looked at me with an unbearable sort of pity.

“It doesn’t work for everyone,” she said.

I scowled.

“How many people hasn’t it worked for?”

“Well…,” she said, “you’re the first.”

But on my second visit a few weeks later, the same docent admitted that I was still the first. She shot me another look as I left, this time mingled with an air of aversion, like my failure was a communicable disease.

“Maybe you just don’t like art,” she said, placing my used electrodes in a bin to be sterilized for future patrons, only touching the device with the very tips of her index finger and thumb.

“Of course I fucking like art. I’m an artist, for chrissakes.”

The docent shrugged.

I let out a half-sigh, half-growl from the very back of my throat, stomped myself towards the parking lot.

One more time, I swore silently, handing over the admission fee and grabbing a device. I followed a gaggle of field-tripping teenagers past the lobby, pasting the electrode patches onto my temples and slipping the plastic headpiece onto the crown of my head. I watched other patrons struggle with the maneuver—putting their EEG devices on backwards, at a loss for what to do with the patches and wires before a docent would come dashing over to assist them. Amateurs, I thought.

I made my way to one of the larger interior rooms of the museum, an octagonal space with natural light pouring through a glass ceiling. The room was textured with chatter from the patrons, their happy squeals at their devices at work, and the sounds of their phones capturing each experience. I tried my best to ignore them.

On each wall hung a half-dozen paintings of various periods and styles. Each piece was spaced quite a bit apart from the others, presumably to allow patrons to gather in big groups beneath them. I glanced around. The painting receiving the least amount of attention was an abstract at the far end of the room, a Kandinsky—in front of which stood a single old bald man in a tweed coat. I made sure my nodes were still attached to my skin and headed decisively for it.

A chaotic bold array of red and blue, yellow and pink, held up the corners of the canvas like support beams. I focused on the lines, the way they upended the viewer’s expectation of what lines could do, the way they subtly morphed into familiar, simplistic shapes. The pleasing way it all balanced itself out and came together. The understanding of form that had clearly gone into the piece, the time and effort and craft. And I waited, teeth clenched, for my EEG device to work.

Nothing happened. And nothing happened for thirty more painful seconds.

It’s the painting, I thought, It’s just not that provocative. And when I looked up I was delighted to see that the old man’s device was equally inactive; he was simply staring straight ahead at the art, his eyes slightly squinted, one foot tapping on the wooden floor. Yes, it was clearly the painting. It was defective. I turned to approach the next picture on the wall when, suddenly, I heard the old man make the strangest sound. I turned back around.

He had laughed. One sustained ha! had burst forth from his belly. Something about the abstraction had amused him, and now he was grinning at the painting, his fake teeth oversized and pearled in his mouth. In one swift movement, his device flickered on, the aperture on the head-mounted projector lens suddenly exposed. It beeped. The palpable hologram appeared like colorful grains of sand falling from nowhere into place, from nonsensical particles into concrete image. And now the man was surrounded by a dozen yellow ducklings, which were quacking and trying to climb his legs, some of their downy feathers coming loose as they jumped from one shoe to another. He kept on chuckling as he started walking in small circles, the ducklings frantically trailing behind him, chirping alarms, as if he were their mother.

“How did you do that?” I demanded, as he passed by me with his flock. He picked up a duckling, cradled it in his hands and brought it to his cheek.

“I’m not sure I did much of anything!” he said. “The painting did it!”

And he led the brood away from me, across the room, hunchbacked and laughing. A crowd stopped to admire them and a woman snapped a photograph, the man posing with a duckling on each shoulder. I looked away, took one step towards the Kandinsky, glared up at it like a playground bully.

“Ha!” I said to it. Was that the codeword? Was that the trick? It did nothing. It hung there.

I spent hours at the museum, trying to get my brain to spur any sort of reaction from the art that would activate the device and its potential interactive holograms. I knew all about many of the paintings—the Warhols, a Van Gogh, some Klints and Twomblys. But there were also pictures of early cave art, sculptures and ancient urns, and even a fingerpainting by an elephant. Nothing triggered the device. By the end, I was so exhausted from staring so intently—trying mightily to find the secret within the artwork that would set it off—that I misread the placard for Picasso’s “Young Woman in a Striped Dress” as “Young Woman in a Stupid Dress,” and sadly resigned myself to a bench beneath it.

The crowd around me was full of people engrossed in the magic of the place. A middle-aged woman in khaki capris was swinging from a hammock that had appeared below a Cezanne, a glass of white wine in her hand. Twin little girls had sprouted white wings from a Bouguereau, which lifted them a few inches above the floor and flew them across the room. Two bearded men and their toddler were being buried in popcorn, which appeared out of nowhere to spill gently onto their heads. But there were less joyful happenings, too. A mother with a child on her hip was quietly crying as she flipped through an old Bible that had materialized. A teenage boy was stuck in a clear box with no door, his panicked shouts incomprensible to his gang of friends, who were yelling at him to quickly look at another painting to make it stop. Most of the patrons, however—whether immersed in joyous or sorrowful or terrifying interactions—were taking pictures, grabbing memories of what the art had done to them, saving them to share with friends and loved ones.

I sat alone on the bench for a long time, stewing in my failure. I stayed so long that I saw the sun begin to set out the museum window. I watched the families start to leave, the teenagers. I stayed so long that the museum was nearly silent now, and I was alone save for one young couple—a woman pulling her boyfriend’s hand as she ran towards a Mondrian.

“Come look at this one!” she said, letting go of his hand and focusing on the painting. Her body erupted in purple butterflies. She giggled, pulled out her phone. “Get a picture!”

He hesitated for a moment before taking her phone, stepping back and snapping a few as she posed in various positions. As he did so, he glanced ever so slightly towards me, and I saw his jaw tighten. I noticed then that he wasn’t wearing his device, but had taken it off, looped it around his arm.

“Sorry, just a few more!” she said, and she bounded across the room away from him, her own body the perfect shadow of a butterfly. The man put his hands in his pockets and stood there, considering all the art around the room in a slow, sweeping motion, taking in each painting for long moments before moving onto the next. His tittering companion, meanwhile, went from painting to painting, jumping in puddles and waving bright yellow banners, hiding in bushes and removing fresh bread from an oven that had sprung up below a Renoir. She took photos of each experience, inspecting each shot afterwards. I looked at the man, who seemed to crumple the longer she pranced around the room.

“Can we go soon?” His voice was soft, discreet, but it echoed through the empty room.

“Just the butterflies, one more time,” she pleaded, and he looked down in a nod, and when she was blanketed in them once again she raced towards him, wrapping her arms around his shoulders, kissing him long and passionately. I watched the back of her head move, the butterflies bat their wings on her shoulders. I watched him not know what to do with his hands, removing them from his pockets only to let them hang at his sides. I watched both their shadows up against the wall, the tension in his shoulders, her joy as she started kissing his neck. I watched him open up his eyes above the lock of her kisses, and look dead into mine from across the room. His eyes were tired, heavy, longing for something else entirely.

He might not have been looking at me. It may have been the Picasso behind me. But I saw him look outward and through me, and though I couldn’t see her face, I knew the joy painted across it shone singularly, blooming unaware of its lack on his own.

From my bench, I saw an ornate gold frame grow around the two of them, mounting them in space. I looked down at my feet, onto which vines were sprouting, tangling themselves up and around my legs, the floor now covered in tall, green grass. The ground, holding me there.

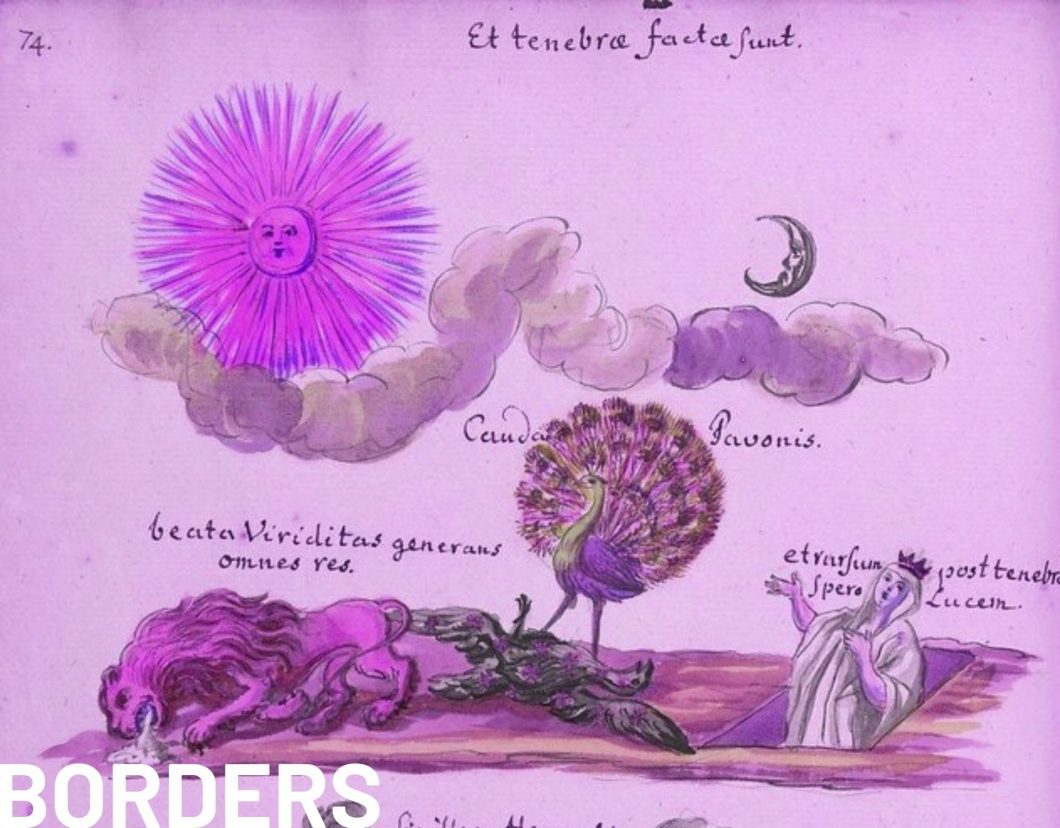

Image: From Thesaurus of Alchemy, ca. 1725. Public Domain.